China’s new ambassadors + mineral monitoring + EU-China in Draghi report

Analysis

Diplomatic tea leaves: What China’s new ambassadors mean for its EU relations

By Claus Soong and Grzegorz Stec

While Brussels spent the summer reshuffling EU Commissioner roles after the European elections in June, China reassigned many ambassadors across Europe. Between May and August, China put new ambassadors in place in 30 countries around the world. New envoys are taking up posts in the EU, Germany, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark Malta, and, outside of the EU, in Switzerland and Belarus.

The appointments are a tactical preparation for upcoming political transitions after elections in Europe and the US, and they may offer early signals of Beijing’s priorities toward Europe in the post-election reality.

Beijing gears up to struggle for stability

Changing up its ambassadors aligns with China’s new "Diplomatic Front," outlined during China’s Foreign Affairs Working Conference in late 2023 and the Third Plenum in mid-2024. Both meetings emphasized building a "benign external environment" (良好外部环境), which means minimizing criticism of China as disruptive to the rules-based international order and countering outside pressures. Pressure from China’s embattled economy is likely contributing to the desire for external stability.

Beijing wants to prevent Europe from further aligning itself with US measures targeting China and to stabilize its relationships with key players like Germany by defusing the EU’s de-risking measures. Its foreign policy priority is to develop stability by limiting disruptions unfavorable to China while maintaining a "struggle" (斗争) mindset. This mindset sees international relations as a zero-sum game and reduces the space for practical cooperation and compromise in a diplomatic setting.

This personnel changes will likely be paired with intensified United Front tactics, which "engage with 'old friends' and co-opt various actors to find common ground,” as senior foreign policy officials stated after the 20th Party Congress in 2022. This approach uses diplomatic practices to sideline and undermine critics of China and to find prospective channels and people to speak for China using its official narrative. Finding such “friends” and appointing diplomats who can strengthen these connections is essential for China to exert its influence.

Keeping up with the ambassadors

Cai Run, the newly appointed Ambassador to the EU is an example of China’s approach to leveraging relationships. Cai’s tenure as Ambassador to Portugal overlapped with António Costa’s time as prime minister. With Costa now serving as the new President of the European Council, Cai’s appointment seems geared toward leveraging their past connection to strengthen ties and foster a more favorable environment for China within the EU. This may lead Cai to focus more on the European Council and individual European capitals rather than the European Commission, which Beijing views as increasingly hostile, especially given its negative assessment of Ursula von der Leyen’s first term as Commission president. His appointment signals Beijing’s intent to explore new personal channels for dialogue with European leaders, despite the overall cooling of EU-China relations.

Deng Hongbo, the new Ambassador to Germany, previously served as Vice Director of the Office of the Chinese Communist Party's Foreign Affairs Commission, a central body in shaping China's foreign policy. In that role, Deng served as the second-in-command under Wang Yi, advising President Xi Jinping on issues of foreign policy. Before that Deng spent 10 years at the Chinese embassy in the US gaining a robust understanding of the country. His appointment underscores Beijing's perception that Germany plays a crucial role in preventing a more confrontational China policy in the EU and hindering the EU’s alignment with US policy on China.

Deng, and likely the other ambassadors, will bring the message of “seeking common ground” between China and Europe, as Beijing continues to maintain that they share extensive common interests with no fundamental conflicts of interest, particularly in economic matters, despite the unfolding tensions.

Beyond the ambassadors to the EU and Germany, it is noteworthy that recent appointments in Belgium and Bulgaria highlight a trend of appointing younger diplomats with stronger foreign language skills to ambassadorships. This may indicate the emergence of the next generation of key Chinese diplomats in Europe in the coming decade.

Reading the tea leaves

It remains to be seen if these ambassadorial shifts signal a broader agenda from Beijing. Meanwhile, three key indicators could reveal whether China is planning a concrete adjustment of its approach to Europe.

First, the new appointees may have arrived with clear instructions. When Fu Cong (傅聪) arrived in December 2022, for example, he was clearly tasked by Beijing with a mission to reinvigorate the frozen Comprehensive Agreement on Investment, along with lifting sanctions between the EU and China. If the new ambassadors – Cai and Deng in particular – come without clear re-engagement proposals, that means Beijing has no major internal reflection or ambition for moderating tensions with Europe.

Another sign of change could come from personnel rotations beyond the embassies – a change in the Department of European Affairs at China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. So far there are no indications such shifts are taking place, with Wang Lutong (王鲁彤) still the department’s director.

Finally, some of the more outspoken diplomats may soften their rhetoric. Ambassador to France Lu Shaye (卢沙野) could be a litmus test given his propensity for confrontational remarks. Lu is currently in Beijing’s good books after he navigated the Olympic Games in Paris and Xi’s state visit to France in April without incident but with desirable messaging for China. Lu is therefore unlikely to be swapped for a more conciliatory diplomat, but should he tone down his communication, that will suggest that Beijing instructed its ambassadors to keep things cordial for the moment.

Yet, even if there is a diplomatic push and Beijing brings some conciliatory offers and rhetoric to the table, China’s strategic goals toward Europe – to hinder transatlantic coordination and erode restrictions on access to European markets and tech – are likely to remain unchanged. The EU and member states should not overinterpret the significance of any charm offensives for long-term trajectory of the relations and must keep building resilience in the face of China’s policy ambitions. Especially as coming weeks will be sensitive, with the EU making its final decision on introducing tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles and setting policy priorities for the next Commission. Ahead of and after the US elections, Beijing will likely intensify its outreach to Europe, especially if a more isolationist administration enters the White House.

Read more:

- Xinhua (CN): The 20th National Congress Press Center Holds Fourth Press Conference, Introducing Comprehensive Advancement of Major Country Diplomacy with Chinese Characteristics

- MFA of the PRC (CN): Central Foreign Affairs Work Conference Held in Beijing, Xi Jinping Delivers Important Speech

- SCMP: China’s new ambassador to Germany pledges to seek common ground

- SCMP: China taps its envoy to Israel as new European Union ambassador

Soapbox-MERICS Data Highlight

China is monitoring the exports of another mineral the Europeans need

The Soapbox-MERICS Data Highlight offers data visualizations of EU-China economic relations. We have partnered with trade specialist Rafael Jimenez Buendía, Lecturer of International Trade at Taltech University in Tallinn, Estonia, and co-founder of “Soapbox,” a free weekly newsletter focused on China trade. In this edition, Rafael and MERICS economics analyst François Chimits delve into the recent extension of Chinese export controls to another mineral. After germanium, gallium and some graphite in 2023, Beijing has included antimony in its export control regime. China is one of the world’s main producers and exporters of antimony.

Rafael Jimenez Buendía:

Beijing announced in August that it has added antimony – a key input in ammunition, infrared missiles, nuclear weapons and night vision goggles, as well as in batteries and solar panels – to its export control list, effective from mid-September. China accounted for roughly half of global extraction of the mineral last year. With this addition, Beijing reserves the right to screen antimony exports on national security grounds.

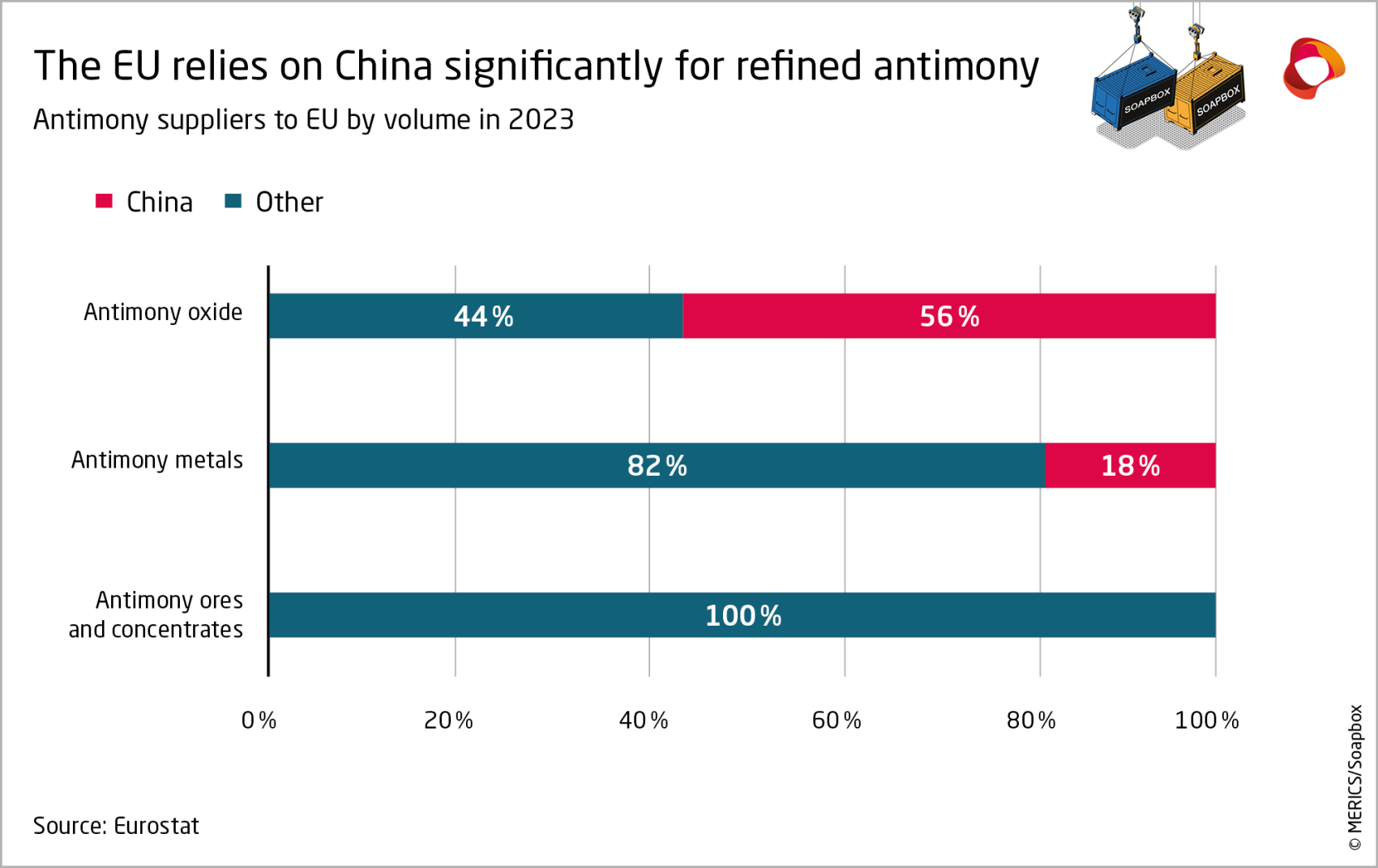

As often with minerals, the inclusion spans various products from extracted to refined materials. The main issue for Europeans is not with sourcing antimony ores, for which they can rely on suppliers like Turkey, which currently meets 100% of its needs, but with processed antimony products. The EU depends on China for about one-fifth of its antimony metal needs and over half of its high-purity antimony oxide imports.

As the Draghi Report highlights, depending on China for critical minerals could be a source of trouble since Beijing’s restrictions on critical raw materials exports increased ninefold from 2009 to 2020.

MERICS Senior Economist François Chimits:

The addition of antimony extends Chinese export controls on critical minerals. Germanium and gallium, key semiconductor inputs, were subjected to controls in summer 2023, followed by graphite, a key component of batteries. Antimony has both commercial and defense applications and is subject to export controls under the plurilateral framework applied by most advanced economies (the Wassenaar Arrangement).

Export controls are not export bans. Beijing will have to issue a license for such exports, collecting information on which entities rely on Chinese antimony. The minerals added over 2023 illustrate that there is often little disruption to supply. It also illustrates that Beijing does not shy away from leveraging supply-chains for geopolitical ends. The US, Japan, and the Netherlands were severed from Chinese germanium and gallium following their own export bans on advanced semiconductors going to China.

The more worrying dimension of this extension is the particularly opaque decision-making on and implementation of Chinese measures to restrain foreign access to parts of technology value chains it controls, as we recently underscored with colleagues in a MERICS report. Contrary to the export controls on dual-use minerals from advanced economies, Chinese measures – including for antimony – also cover the technology to extract and process those raw materials in which it often has a technological edge.

The addition of antimony to Chinese export controls is nothing to panic about, but surely a new critical supply-chain for the Europeans to tightly monitor. Europeans should also consider more efforts to diversify away from China, something the US has initiated with a Pentagon-financed project expected to begin production in 2028.

Update

Draghi calls for an EU ripe for competition with China

Mario Draghi’s report on the future of EU competitiveness was made public on September 9. Commissioned by the President of the European Commission almost a year ago from the esteemed former central banker and Italian prime minister, the 400-page document paints a well-sourced picture of a European continent slowly but surely falling behind in terms of innovation and productivity, posing an “existential challenge” for European economies. The bleak assessment and the long list of bold recommendations, structured around five horizontal matters and ten sectoral focuses, ought to feed into the discussions of the new Commission’s priorities for the next five years. The 2019 discussions set the tone of a much more “geopolitical commission” that assertively stood up for its interests internationally.

What you need to know:

- Get fit for competing with China: Economic, technological and geoeconomic competition with China features strongly in the document, echoing fears that Europe could fall behind. With close to 400 mentions, no other country gets as much attention. If an exact assessment of Chinese techno-innovation capacities is still heatedly debated among experts, Europe’s political elite widely recognizes China as a state-of-the-art competitor.

- A source of inspiration and urgency: The report underscores China’s tremendous economic and technological progress over the past two decades. Drawing from that experience, Draghi calls for European industrial policies to allocate more resources to key industries and technologies. Together with the deepening of the single European market and efforts to pool education, research, and foreign policy in strategic sectors where green industries, commodities and digital technology feature high, this blueprint has parallels with China’s reform orientation under Xi.

- A challenging partner: The report also addresses the challenges China poses for European economic interests. It points to China’s massive industrial subsidies as a threat to European prosperity, especially as “an increasing number of countries are raising barriers against China, redirecting Chinese overcapacities towards the EU market.” It identifies dependencies on China in minerals and in green industries as a serious source of concern that ought to be addressed with pro-active diversification. Finally, after mentioning growing Chinese investments in Europe, the report warns against the risk of “small Member States” having “unwelcome concessions extracted by foreign countries.”

Quick take: The policy agenda of the second Commission led by Ursula von der Leyen, which she presented to parliament before the summer break, has already taken some key elements on board. The competitiveness mantra focused on technology and innovation, foreign economic policy, and the sectoral prioritization of green and high-tech industries are very similarly worded in both documents. More supportive industrial measures can be expected from Brussels in sectors with significant Chinese competitors, without any indication of a reduction in its more protective agenda against Chinese economic distortions. The next Commission is hence most likely to maintain the same bumpy EU-China economic relations of the past few years. Exactly what aspects of the report will spill over into European policies is yet to be discussed by member states in the Council, where fierce debates are expected.

Read more:

- European Commission: EU competitiveness: Looking ahead

- Groupe d'études géopolitiques: Draghi's report: A force for reform

- Euractiv: EU politicians weigh in on Draghi report

- European Commission: Political Guidelines For The Next European Commission 2024−2029

Short takes

New European Commission unveiled by Ursula von der Leyen

On September 17 in Strasbourg, the European Commission President released the proposed lineup of her new cabinet. Portfolios most directly connected with China-related policy went to Estonia, France, Spain, and Slovakia. The make up of the Commission may yet change, as the proposed Commissioner candidates still need to be approved by the European Parliament.

Europeans expected to vote on EV tariffs next week

The much-anticipated European Council vote is expected to take place on September 25. It comes after the EU rejected China’s proposal to set minimum prices and volume caps instead of the bloc applying tariffs. The measures will be implemented by the end of October unless they are opposed in the vote by qualified majority of 15 member states representing 65 percent of EU population. Berlin and Madrid are now publicly opposing the tariffs.

- Euronews: EU rejects price offer from Chinese EV producers as talks enter final stretch

- Reuters: EU plans Sept 25 vote on raising tariffs on EVs from China, Bloomberg News reports

- Bloomberg: Germany Lines Up With Spain Against EU Tariffs on Chinese EVs

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez visited China

The visit took place September 8-11 and showcased Beijing’s carrot and stick approach to get European capitals to oppose the tariff vote. Before the Spanish Prime Minister’s trip, Beijing’s anti-dumping investigation raised the possibility of a tariff on EU pork imports. Spain topped that sector exporting to China EUR 1.2 billion worth of pork in 2023. During Sánchez’s visit, China’s Envision Group announced a nearly EUR 1 billion investment in a plant to manufacture green hydrogen machinery. Madrid was one of the key proponents of the EV-related tariffs, but at the end of the visit Sánchez called for “reconsidering” the move.

- Reuters: China's carrot-and-stick with EU trading partners start to pay off

- Reuters: China's Envision to invest $1 bln in Spain to make green hydrogen machinery

- Bloomberg: Spain Breaks EU Ranks With Sudden Call to Drop China EV Tariffs

European business confidence in Chinese market crumbles

The annual position paper of the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China indicated that business confidence had reached an “all time low.” The paper puts forward over 1,000 recommendations for Chinese authorities and points to challenges created by lagging domestic demand, sectoral overcapacity and geoeconomic tensions.

Two German warships visited the Philippines after sailing through Taiwan Strait

The freedom of navigation operation marks the first such visit and pass by the German Navy in over 20 years. It comes at the time of heightened tensions in the South China Sea after Chinese and Philippine Coast Guard ships collided in the Spratly Islands area. The German ships were shadowed by the People’s Liberation Army Navy throughout their journey.