Debunking three myths about the end of presidential term limits in China

Descriptions of Xi Jinping as new Mao Zedong or destroyer of the Deng Xiaoping legacy are prominent in the media outside of China. But resorting to old paradigms about leadership in Chinese politics may prevent us from seeing the differences between Xi and his predecessors.

Ever since the Chinese legislature, the National People’s Congress (NPC), voted on March 11 to remove the two-term limit on the presidency from the constitution, media coverage has been dominated by historical determinism. Xi Jinping, the incumbent Chinese state president, has been labeled a "president for life" or a "new emperor" and the future of Chinese politics has been assessed as a reversion "to the days of Mao Zedong" or a "dismantling [of] the Deng-era project." However, resorting to the old paradigms prevents us from seeing the differences between the past and the present. Xi Jinping is neither the "new Mao" nor the "terminator of Deng's reform project." He wants to protect his party as well as his predecessors from the latent crisis. By abolishing the term limit on the presidency, an inconsistency of the Chinese constitution is eliminated, which could have led to a split in the party leadership. The newly-updated constitution is still not enough to extend Xi’s presidency for life.

Myth 1: President Xi is a “New Mao”

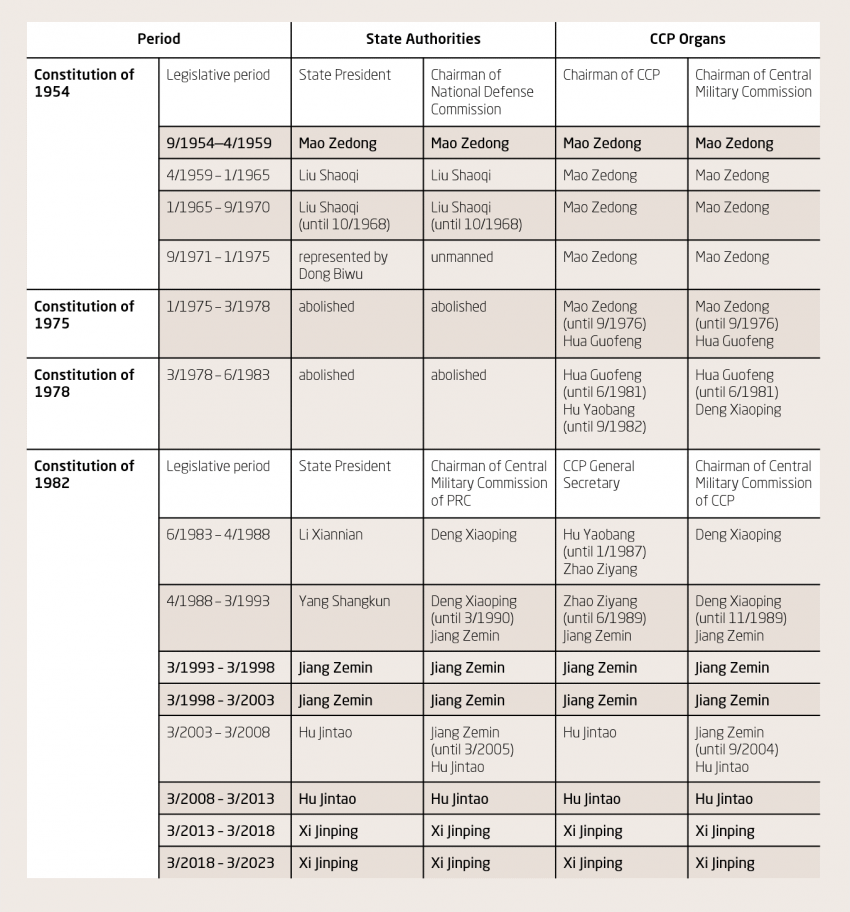

Many US journalists like to compare Xi Jinping with Mao Zedong, the founding father of the People's Republic of China (PRC), but how far does this comparison actually coincide with historical facts? The following chart shows the different leadership structures in Chinese politics that have resulted from the four constitutions since the founding of the PRC in 1949. As we know, those who hold the powerful posts of head of state, party leader, or chairman of the military commission are the key political decision-makers in the Chinese system. In particular, those who head the national armed forces have much more political weight than the other posts (the column on the right in each section of the chart).

The chart shows that Mao headed both state bodies and party organs only in the first legislative period between 1954 to 1959. After that, he withdrew from all posts in state bodies and handed them over to his party colleague, Liu Shaoqi. Over the following ten years (1959-1968), there was formally a dual structure of leadership in Chinese politics that inevitably led to a bitter power struggle between Mao and Liu. The power struggle ended when Liu Shaoqi was expelled from the party and suspended from his position as head of state in 1968. After then, the state authorities did not have any leadership. Obviously, Mao never attached much importance to the presidency. He even had it completely removed from the constitution in 1975.

Myth 2: Deng Xiaoping brought an end to Mao’s autocracy

Another incorrect characterization is that Deng Xiaoping wanted to bring Mao’s one-man rule to an end. As the chart shows, Mao exercised his predominance in Chinese politics between 1968 and 1976, especially through his two powerful posts as chairman of the party and chairman of the Central Military Commission of the CCP. If Deng really wanted to terminate Mao's one-man rule, he would have tried to weaken Mao’s own posts, not the posts Mao gave up.

According to literature posted by the National People's Congress as learning materials on Chinese constitutional history, the presidency was reintroduced in the 1982 constitution as an intended balance of power mechanism by strengthening the party leader's opposition. However, the power of the presidency was significantly weakened compared to the constitution of 1954 on Deng Xiaoping's initiative. The head of state should not only be limited to two terms, but he also would fulfill primarily representative tasks and have no authority to interfere in political daily business. In addition, the leadership of the national armed forces, which the constitution of 1954 attributed to the state president, was also moved away from the presidency.

By contrast, the Central Military Commission of the PRC, which was reintroduced in the 1982 constitution, has a chairman position which is neither prescribed a term limit nor the obligation of providing a work report to the NPC. Thus, this position became the only exception in the constitution of 1982, which was also Deng’s idea (see the history of the Central Military Commission of the PRC).

Myth 3: Xi ended Deng’s reform project

Another inaccurate assumption is that the concentration of power in one person signals a turn away from Deng's reform project. As the chart shows, the division of the leading positions among several different persons since 1982 only occurred between 1983 and 1993. After 1993, power was centralized in one person, namely Jiang Zemin. A big difference between Mao's era and the state of affairs today is that the state authorities were abolished during the Mao period but exist under President Xi.

Jiang Zemin upgraded the role of the presidency in foreign affairs, without changing the constitution. As state president, he completed numerous oversees state visits and other modes of travel, which became increasingly important alongside China's increasing integration into the global economy. His successors also follow this informal rule.

However, the structure of leadership that centralizes power in one person (the so-called "Trinity" according to Xinhua) was not initiated by Jiang, but by Deng. It is considered to be a consequence of the constitutional crisis during the student protests from 1988 to 1989. Disagreements between the former leaders escalated conflicts between the students and the government, resulting in the intervention of the People's Liberation Army. After the violent crackdown in Tiananmen Square, Deng Xiaoping stepped down from his post as chairman of the military commissions, and appointed Jiang Zemin as his successor, as the successor of the former secretary general of the party, and as the successor of the state president. In this way, Deng himself terminated his own reform project without publicly announcing it (see source).

The outlook for the future

The centralization of power in one person revealed the inconsistency of the constitution when Jiang Zemin lay down the presidency after two terms in 2003, but maintained the leadership of the military commissions for another two years. Between 2003 and 2005, the dual structure of leadership that Deng wanted to terminate in 1993 came back (see chart). Although there was no apparent division between the two core leaders at that time, the blockade of political decision-making affected almost the entire tenure of Hu Jintao. This indicated that the constitutional inconsistency could easily undermine the "Trinity."

The new constitutional amendment has only brought into line the term of the presidency and of the chairman of the Central Military Commission of the PRC. China’s head of state position remains primarily a representative function. Viewed from a constitutional standpoint, the "trinity" of positions is not yet fully backed by the constitution. The constitution’s inconsistency is thus only halfway solved. Therefore, further constitutional amendments cannot be ruled out, and are possible following the restructuring of the army in 2020, when the head of state could be authorized to also head the military forces indefinitely. Then it would be conceivable that a presidential system could emerge in China. However, there is still a long way to go for this to become a reality.

This article was first published by China-US Focus on 29 March, 2018.