China-Kenya relations: Economic benefits set against regional risks

You are reading chapter 5 of the MERICS Paper on China "Beyond blocs: global views on China and US-China relations". Click here to go to the table of contents.

You are reading chapter 5 of the MERICS Paper on China "Beyond blocs: global views on China and US-China relations". Click here to go to the table of contents.

China and Kenya have a relationship of enhanced economic cooperation, though the trade balance heavily favors China and concerns over debt sustainability have grown with Chinese lending. Closer economic ties have paved the way for more security cooperation. However, the resulting geopolitical rivalry risks exacerbating political fragmentation in East Africa and the Horn of Africa as countries align themselves with either the West or China. Amid these pressures, it remains to be seen how effectively Kenya can triangulate between China and the West. How will Nairobi manage to forge mutually beneficial relations with the West and yet sustain constructive engagement with China?

Status-quo: Economic ties open the door to more security cooperation

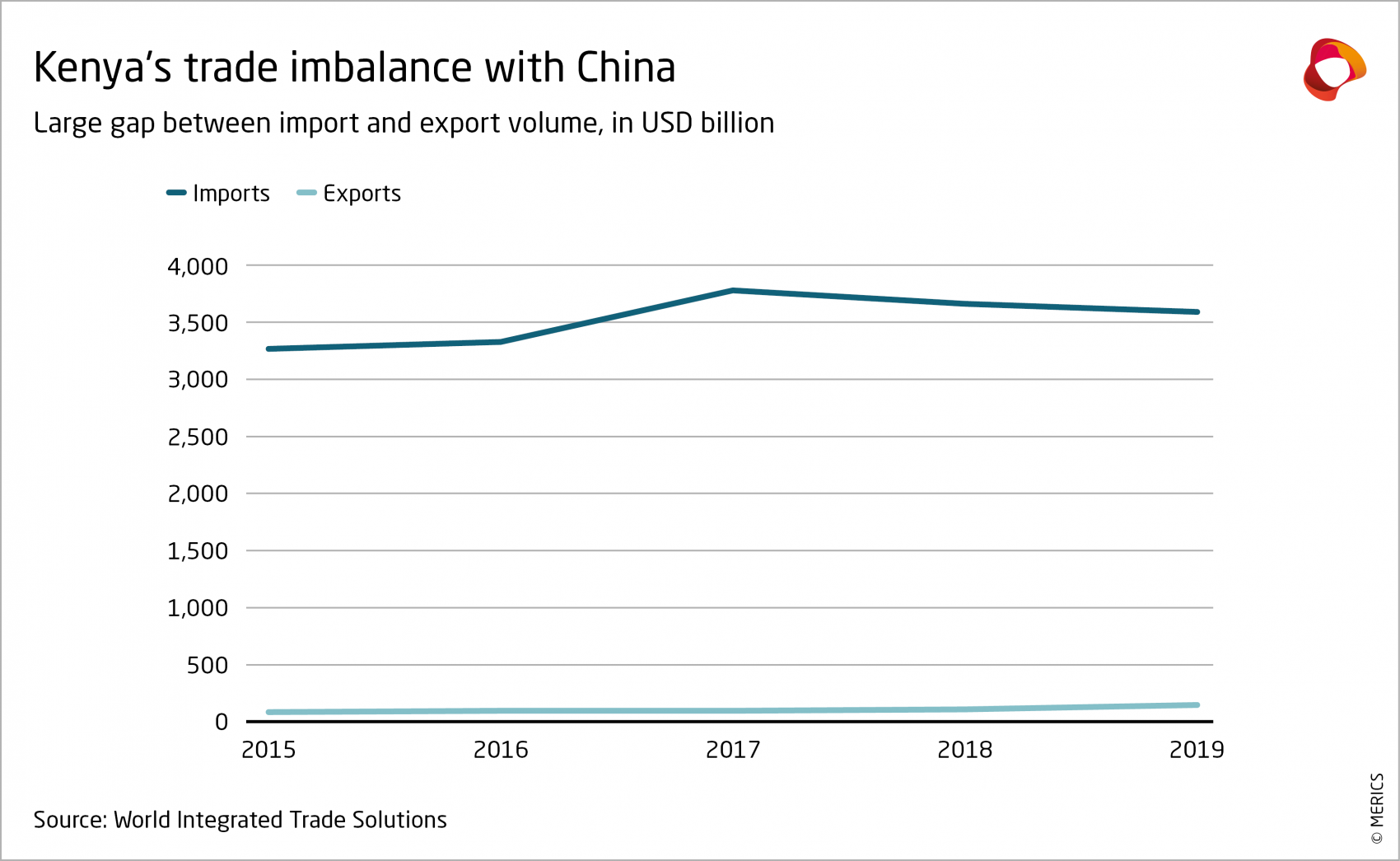

Since 2015, bilateral trade between China and Kenya has been on the rise (see Exhibit 1). From 2015 to 2019, the total trade value between the two countries was USD 18.20 billion.1 Of this, Kenya’s imports from China made up 97 percent, while Kenya’s exports to China were a mere 3 percent, thus the trade balance skews heavily in China’s favor. Imports rose due to Kenya’s engagement with China’s Belt Road and Initiative (BRI), especially from the start of the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) project in December 2014.2 The incorporation of the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor project into the BRI also had a significant impact. The slight increase in Kenyan exports during the same period suggests Kenyan exporters may have discovered some sustainable opportunities in China’s market. The growing trade deficit is underpinned by the fact that China’s leading exports to Kenya are electrical equipment and machinery, predominantly used in the construction sector, while Kenya’s leading exports to China consist of mineral ore slag, soda ash and some agricultural products. The imbalance has prompted concern among policy makers about the need to review China-Kenya trade policy.

Meanwhile, since 2005, the Kenyan Investment Authority (KenInvest) has registered and facilitated 313 Chinese investment projects with a total value of USD 1.55 billion (see Exhibit 3).3 This far outstrips US investments in Kenya, which stood at USD 353 million in 2019.4 Kenya’s experience is consistent with the general pattern of declining US investment flows into Africa since 2010.5 Chinese investments in Kenya increased significantly when the SGR kicked off in 2014, as the rail project generated new investment opportunities in the construction and manufacturing sub-sectors. Chinese firms have also helped Kenya reduce dependence on imported commodities, especially in high tech fields like cloud computing.6

Rising trade and investment was reflected in the growth of Chinese loans during the same period. By the end of 2021, China was the leading bilateral creditor to Kenya, representing about 67 percent of its external debt, followed by Japan with 14 percent and France at 7 percent.7 As a significant proportion of Chinese loans are commercial, politicians have raised concerns about the potential impacts of fluctuating interest rates and long repayment periods.8

Amid deepening economic ties, China’s conceptualization of its national security interests has widened. In the 2000s, China sought to secure its maritime safety from pirates along the major sea lanes connecting East Africa to Chinese ports.9 China’s presence in the construction of mega infrastructure projects in Kenya has also generated security concerns arising from local frustrations over lack of job opportunities for Kenyans. Friction could have been avoided at the negotiation stage if Kenyans had insisted on legally binding agreements on local content.

The construction of the SGR saw several security problems, including attacks from locals and terrorist threats.10 To protect its assets during construction, China set up security services and trained an elite Kenyan police division.11 In addition, China Bridge and Road Corporation (CBRC) procured the services of private security company DeWe, which developed a “comprehensive security plan” for the SGR infrastructure project involving security personnel, security technology and coordination. CBRC also entered into a partnership with the Kenyan Police Service for the services of 1,500 armed police officers. The presence of Chinese private security companies has increased Kenyan citizens’ perception of insecurity and reduced trust in the police’s ability to maintain law and order. The Afrobarometer12 survey in the month of November 2021 found Kenyans ranked crime and security as the sixth most important problem, with citizens reporting 34 percent trust in police,13 down from 38 percent in 2021.

During the January 2022 visit of China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi, peace and security topics were discussed, in recognition of Kenya’s position on the United Nation Security Council (UNSC)14 – a seat that China may leverage to influence Kenya’s position on UNSC matters in future. China’s growing interest in Kenya’s security sector has stirred a Western reaction; the United States has claimed China is planning to set up a military base in Kenya similar to the one in Djibouti.15 US anxieties are understandable as it has traditionally played a greater role in Kenya’s national security than China, especially in supplying military equipment and the fight against terrorism.

Geopolitics: Kenya plays off China and the west for development goals

China’s growing economic power and heightened engagement in Africa enhances the geostrategic importance of anchor states like Kenya. In the early 2000s, Kenya’s foreign assistance came mainly from the West and stood at approximately USD 750 million.16 China’s presence meant Kenya could diversify its external sources of development assistance, so that by late 2018, Chinese loans in Kenya stood at USD 4.75 billion.17 Kenyan policy-makers tend to perceive Chinese development assistance as free from onerous conditions and therefore favor it as a counterweight to Western aid, which is often pegged to good governance.

Kenya has gained diplomatic space to manoeuvre in its engagement with the West by wrapping infrastructure mega-projects into the BRI, and thereby being loosely associated with China’s global geopolitical ambitions. Beijing’s readiness to enhance Kenya’s position as East Africa’s main gateway is perceived in Kenya as a Chinese strategy to counter Western influence. However, Kenya maintains a supple position on whether it favors the West or the East, which depends on the context.18 When US President Barack Obama visited in 2015, President Kenyatta stressed Kenya’s openness to constructive engagement with all countries.19 During his second state visit to China in September 2018, President Kenyatta affirmed his country’s commitment to an “interconnected world [through the BRI].”20 Although Foreign Minister Wang’s visit to Kenya was part of China’s annual diplomatic visits to Africa, it came barely six weeks after a visit from US Secretary of State Antony Blinken. Whereas Blinken was hosted in Nairobi, Wang flew directly to the coastal city of Mombasa where he inspected an oil terminal funded by China’s Exim Bank at a cost of USD 400 million.

Although Kenya wants to engage with both sides, it is increasingly likely to find itself aligning with China, given the attractions of economic cooperation with no strings attached. However, this strategy appears strained. At the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Kenya voted for the resolution calling on Russia to withdraw its troops from Ukraine. However, as the situation unfolds Kenya may reevaluate its position, opting to maintain a strategic equal distance between the axis represented by NATO and democracies and the Russia-China authoritarian axis.

Perceptions: Mixed views on China’s growing presence

The Afrobarometer survey asked respondents whether they thought China, the United States or Japan had positive or negative economic and political influences on Kenya. Among Kenyan respondents, 54 percent felt China was a positive economic and political influence; favorable views of the United States were only slightly higher at 57 percent, while Japan received positive responses from 39 percent.21

However, views varied within different sections of Kenyan society. For instance, among Kenyan businesspeople, perceptions are informed by whether they gain or lose from China’s presence. Small traders in Nairobi complained that Chinese traders are squeezing them out of business: “They usually come to our shops disguised as customers and ask for our prices, only to go back to their country and bring to the market the same products at a much lower price.”22 On the other hand, Kenyan political elites were generally positive about China’s engagement. One leader observed that, “Beijing acted nicely and generously to really promote its long-term strategic and political objectives in Africa.” As in other African countries, the lack of socio-political conditions on loans and China’s general indifference toward Kenya’s domestic politics were welcomed by Kenyan elites who compared China’s stance favorably with the conditions put on Western support. However, Kenya’s foreign policy toward China may be impacted by the erosion of optimism about increased cooperation, particularly in relation to the trade deficit, which could have implications for the BRI’s future there.

Outlook: Unsustainable trends in need of revision

Concerns over the trade deficit provided the impetus for a review of trade relations. In 2018, the two countries began talks on a sanitary and phytosanitary protocol to expand market access for Kenyan products in China. Kenya is pushing for a review of tariffs levied on cut-flowers and vegetable exports. During Wang’s visit, Kenya and China signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) and set up a working group to look into tariff and non-tariff barriers to Kenya-China trade. The declared aim was “to fast-track and increase exports from Kenya and China.” They also signed two protocols to facilitate trade, particularly exports of Kenyan avocados and aquatic products.23 Although Kenya’s economy has remained resilient during the pandemic, its growing debt problems may predispose the country to default on Chinese loans in the near future.24 On the security front, geopolitical rivalry is likely to exacerbate regional political fragmentation, as countries align themselves with either the West or China. It remains to be seen how Kenya will manage the inevitable pressures of balancing between its Western and Chinese partners.

- Endnotes

-

1 | World Integrated Trade Solution (WITs), https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/KEN/Year/2019/TradeFlow/EXPIMP/Partner/CHN/Product/all-groups. Accessed: 10 January 2022.

2 | The SGR project (Phase One, Mombasa- Nairobi 488 kilometers) is Kenya’s largest infrastructure project since independence in 1963, worth USD 3.2 billion. The project started in December 2014 and began operation in June 2017. This explains the reduction in imports from 2018.

3 | The law does not mandate foreign investors to register with KenInvest (The Investment Promotion Act, 2004), so the data does not reflect all Chinese investments in the country.

4 | US, 2021 Investment Climate Statements: Kenya, https://www.state.gov/reports/2021-investment-climate-statements/kenya/ Accessed: 10 January 2022.

5 | China-Africa Research Initiative - Chinese Investments in Africa, http://www.sais-cari.org/chinese-investment-in-africa. Accessed: 21 March 2022.

6 | Phyllis Wakiaga, Chief Executive Officer, Kenya Association of Manufacturers, Chinese firms boosting Kenya’s manufacturing sector via technology https://newsaf.cgtn.com/news/2021-09-14/Chinese-firms-boosting-Kenya-s-manufacturing-sector-via-technology--13x2mTtdSUg/index.html. Accessed: 19 March 2022.

7 | Okoth, Jackson “China is the Top Bilateral Lender to Kenya- Central Bank,” 19 September 2021 https://kenyanwallstreet.com/china-has-invested-heavily-in-kenyas-roads-rail/. Accessed: 19 March 2022.

8 | Miriri, Duncan, China’s foreign minister visits Kenya amid unease over rising debt, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-foreign-minister-visits-kenya-amid-unease-over-rising-debt-2022-01-05/ Accessed 21 March 2022.

9 | European Parliament, 2019. China's growing role as a security actor in Africa https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2019/642232/EPRS_BRI(2019)642232_EN.pdf. Accessed: 22 December 2021.

10 | Shuwen Zheng and Ying Xia. 2021. Private Security in Kenya and the Impact of Chinese Actors. Working Paper No. 2021/44. China Africa Research Initiative, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University, Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.sais-cari.org/publications.

11 | Ibid.

12 | Afrobarometer is a Pan-African, non-partisan survey research network that provides reliable data on Africans’ experiences and evaluations of democracy, governance, and quality of life. With sample sizes of 1,200 or 2,400 adult citizens, the survey yield margins of sampling error of +/-2 to 3 percentage points at a 95% confidence level.

13 | In the survey, the respondents were asked what they thought were the most important problems facing Kenya that the government should address: management of the economy, unemployment, corruption, health and education topped the list.

14 | Kitimo, Antony, “Chinese foreign minister to visit Kenya in Africa tour,” The East African 4 January 2022, https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/business/chinese-foreign-minister-africa-visit-3672274.

15 | The East African, China hits out at the US over Kenya military base claim, 8 November 2021, https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/news/east-africa/china-hits-out-at-the-us-over-kenya-military-base-claim-3611798. Accessed: 22 December 2021.

16 | Prizzon Annalisa and Tom Hart. 2016. Age of Choice: Kenya in the new development finance landscape, Overseas Development Institute, https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/10986.pdf. Accessed: 8 January 2022

17 | Were, Anzetse, Debt Trap? Chinese Loans and Africa’s Development Options, South African Institute of International Affairs, Policy Insight, No. 6 https://media.africaportal.org/documents/sai_spi_66_ were_20190910.pdf. Accessed: 20 March 2022.

18 | It is not easy to determine whether Kenya already experienced pressure from the US (or from China) to reassess ties with the other side.

19 | Basu Pratyusha and Milena Janiec (2020). Kenya’s regional ambitions or China’s Belt-and-Road? News media representations of the Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, doi:10.1111/sjtg.12350

20 | Ibid.

21 | The reduction could be attributed to debates around increasing Chinese loans in Kenya, compounded by the quick spread of the Covid-19 after Covid-infected airline passengers from China were not quarantined.

22 | Mwaura, Samora 2013. “Who is the Bull in a China Shop?” The Daily Nation, 31 March 2013.

23 | Yusuf, Mohammed “China to Appoint Horn of Africa Special Envoy,” VOA, https://www.voanews.com/a/china-to-appoint-horn-of-africa-specialenvoy/6385449.html, accessed 10 January 2022.

24 | “Kenya GDP Annual Growth Rate,” Trading Economics, accessed September 5, 2021, https://tradingeconomics.com/kenya/gdp-growth-annual; Carmody, Pádraig; Ian Taylor, and Tim Zajontz, “China’s spatial fix and ‘debt diplomacy’ in Africa: constraining belt or road to economic transformation?” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue canadienne des études africaines (2021), 8.

You were reading chapter 5 of the MERICS Paper on China "Beyond blocs: global views on China and US-China relations". Click here to go to the table of contents.

You were reading chapter 5 of the MERICS Paper on China "Beyond blocs: global views on China and US-China relations". Click here to go to the table of contents.