The global struggle to respond to an emerging two-bloc world

You are reading the introduction of the MERICS Paper on China "Beyond blocs: global views on China and US-China relations". Click here to go to the table of contents.

You are reading the introduction of the MERICS Paper on China "Beyond blocs: global views on China and US-China relations". Click here to go to the table of contents.

Key takeaways

- China’s ambitions and international behavior are increasingly felt as challenges to European interests and security and have attracted growing skepticism in European countries. For many EU capitals, systemic rivalry is becoming the dominant framework through which decision-makers look at relations with China.

- This view is not fully shared even within the EU, and it is certainly not universal at the global level. Attitudes towards China’s rise are as numerous and varied as the UN’s member countries, many of whom take a more critical view of the United States and the West than of China.

- Beijing seeks to exploit this skepticism to deepen ties with the Global South, aware that its ambition to return to global power status by 2049 will hinge on how these countries respond to US-China rivalry.

- Few countries want to take sides in this competition, but they may find themselves pushed to do so at some point. It is therefore imperative for European capitals to understand how the rest of the world perceives a rising China and Beijing’s rivalry with Washington.

- Contributors to this study reported on perceptions in Bangladesh, Chile, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. All said their countries’ ties with China have strengthened over the last decade.

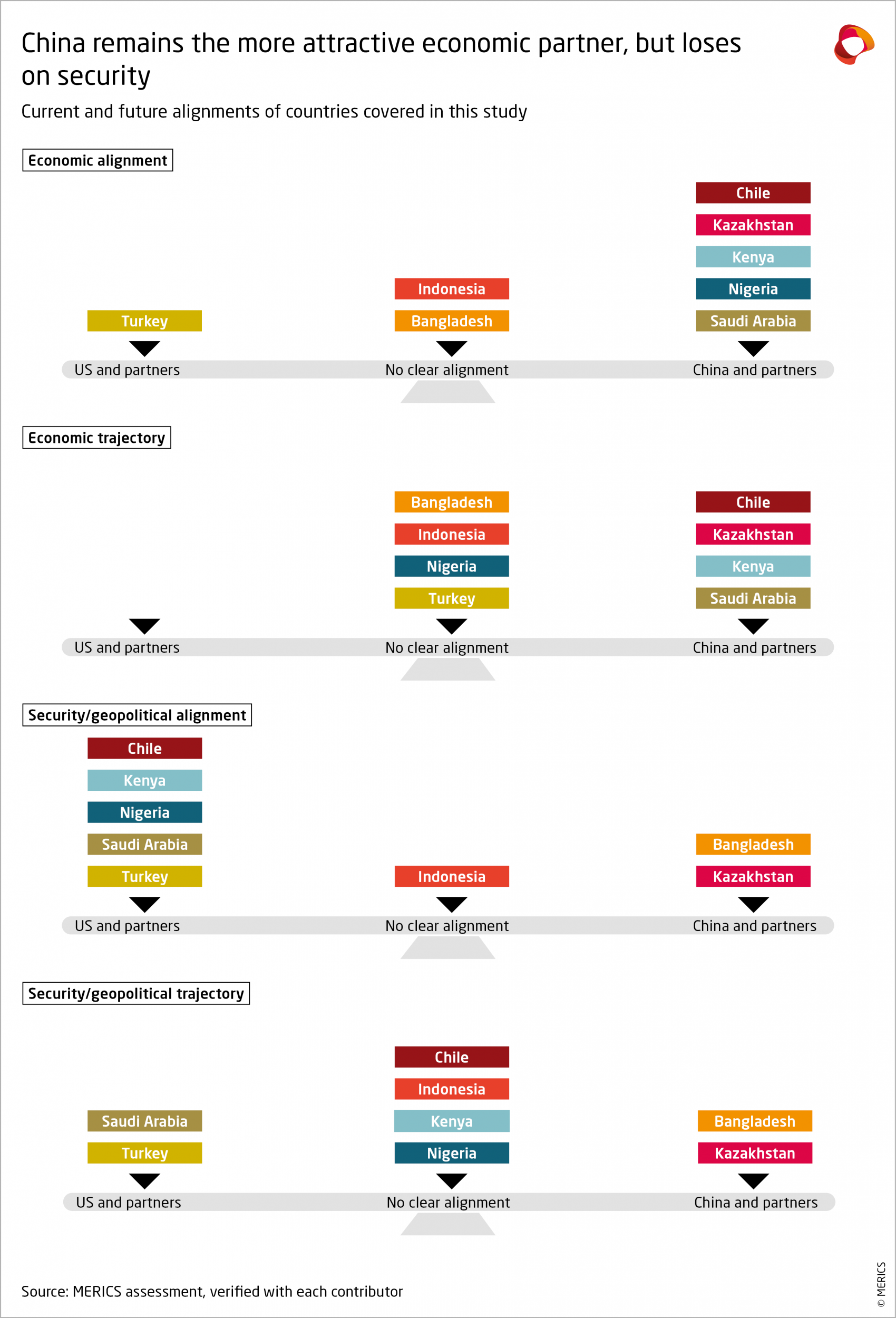

- On US-China rivalry, contributors noted a general tendency to lean towards the United States as a security partner and China as an economic partner. All the countries examined here opposed taking sides; their governments hope to continue seeking out opportunities that arise from US-China rivalry.

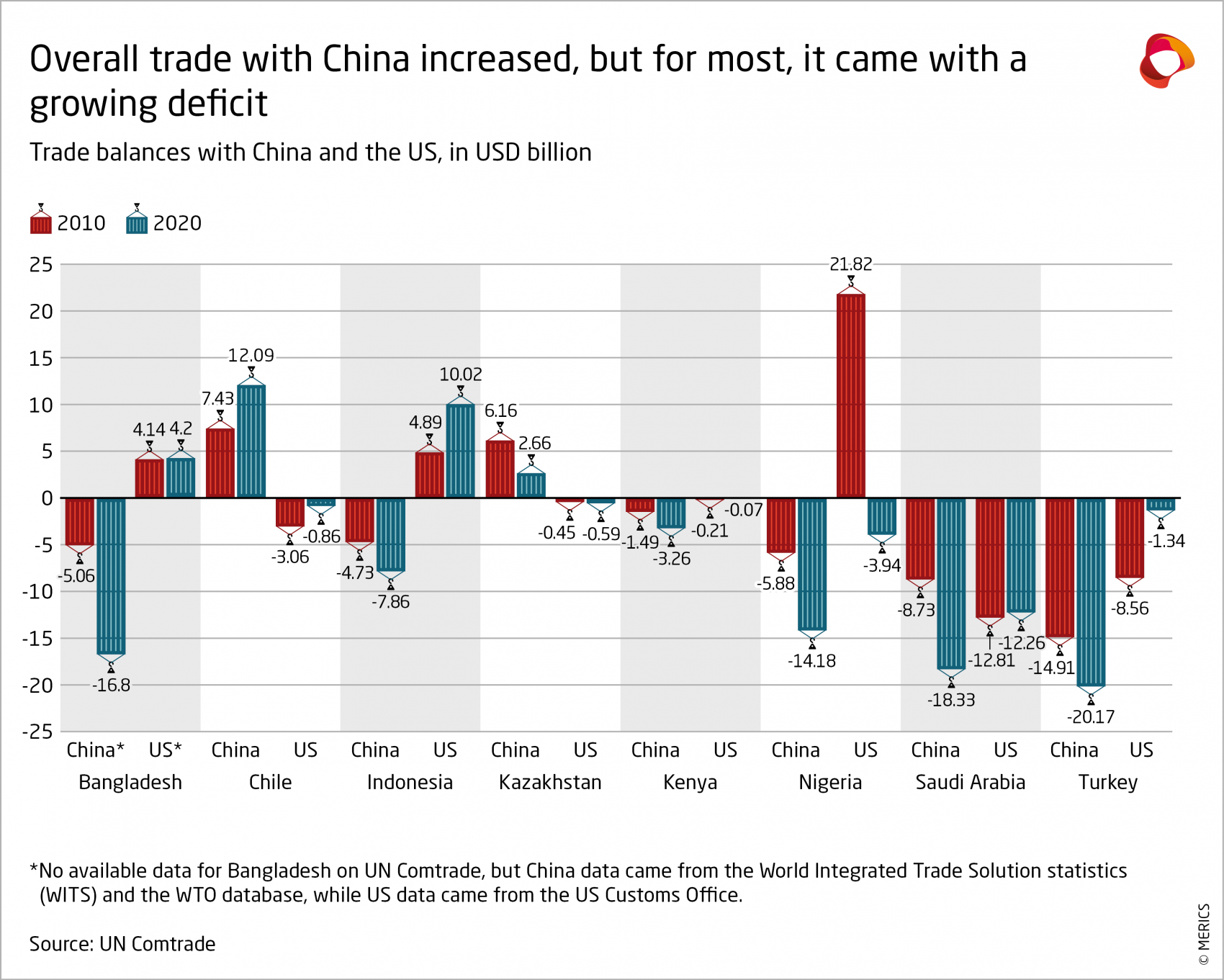

- China’s economic engagement with each of the eight countries considered here has expanded – through trade, FDI, infrastructure financing and project facilitation – but the trend is overwhelmingly lopsided. China’s exports, investment and financing have risen, while flows in the other direction have failed to keep pace in almost every case.

- Security ties with China remain limited for most of the eight, but the trend is towards expansion, both in military-to-military cooperation and in arms imports. Some welcome China as a security partner to lessen reliance on the United States as a security provider.

- China is working to expand its network of friends and partners by leveraging its position across multiple regions as an important economic partner and as a geopolitical alternative – or counterbalance – to the United States and Europe.

- European governments and the European Union should not lose sight of these developments. Growing global bipolarity is certain to have substantial impacts on European interests and security in many countries and regions, often of key strategic importance to the EU.

Introduction: The global struggle to respond to an emerging two-bloc world

"It’s not a question of one country or the other per se; it’s really a question of the best deal that we can strike." Nigerian Foreign Minister Geoffrey Onyeama, November 19, 2021

Even prior to the pandemic and invasion of Ukraine, Europe was struggling to find the best approach to the emerging international dynamics of a post-unipolar world. As the underlying fabric of the rules-based global system gets stretched – between the United States and its partners, China and its growing list of friends, and everyone else in the middle – the sense that a two-bloc world is gradually re-emerging is greater than at any time since the Cold War. It was accelerated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine only a few weeks after China and Russia reaffirmed their “no limits” partnership and committed to solidify their own bloc. European leaders now face some stark realities as the rules-based international order they are used to risks being undermined by this new dynamic.

However, countries all over the world are attempting to respond to shifting global dynamics and a rising China, not just close allies of Beijing or Washington. And Beijing sees what is at stake very clearly: the success or failure of its ambition to regain global power status by 2049 and play a central role in reforming the present international order hangs on how countries outside the traditional “West” respond to its growing strategic footprint and rivalry with the United States.

It is of major importance to European leaders to understand how actors outside the usual grouping of rich, liberal market economies view this changing ecosystem, and how they think about Europe in a complex world of actors who all have agency. To that end, we commissioned eight contributors to describe their countries’ views of China and US-China rivalry. Their analyses cover Bangladesh, Chile, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. The eight countries were chosen for their geographic and cultural diversity, varied levels of development, different government types and varied degrees of proximity to China.

Contributors universally reported that their countries “do not want to ‘choose’” between Beijing and Washington – instead, governments hope to remain in the middle and see what opportunities might emerge out of US-China competition over third countries. However, it is possible these countries may nevertheless be pushed to “choose.” There is therefore a pressing need to understand their interests and perspectives better now, rather than after the fact.

More immediately likely, however, is that these eight countries (and others too often overlooked by European leaders) might choose sides in smaller, specific matters under the rules-based international system. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine provided a glimpse as to how such matters can play out. When the UN General Assembly (UNGA) held a vote in early March 2022 on a resolution to condemn the invasion, 141 countries supported it, 35 abstained, and 5 opposed. Of the eight countries selected (prior to the invasion) for this project:

- Abstentions came from Bangladesh and Kazakhstan, countries with close ties to Russia, or to the USSR in the past.

- Two votes in support came from Chile and Turkey, which have mutual defense pacts with the United States; the third, Saudi Arabia, is heavily reliant on the United States as a security provider.

- The remaining three – Indonesia, Kenya, and Nigeria – also voted in support of the resolution. All have much larger trade flows – all of which are surpluses – with the United States than with Russia.

From a European perspective, it is worth considering how these eight countries, and others in their respective neighborhoods, might exercise their agency and leverage their positions in multilateral institutions. Or within the emerging blocs, if push comes to shove. Compared with modern Russia, China’s vastly larger economic ties with much of the world, coupled with its growing role as a security provider to a swathe of countries, would likely produce very different calculations if UNGA members were asked to vote to condemn something China did. Add to this that Beijing has repeatedly demonstrated willingness to use economic coercion when faced with even minor diplomatic slights. This dynamic begs two questions: would the 141 countries that condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine do the same if China had been the aggressor? What does Europe need to do to enhance its value in the eyes of such countries to shift the calculus in favor of the rules-based system?

Key trends: Chinas narratives in western liberal democracies are not mainstream in the rest of the world

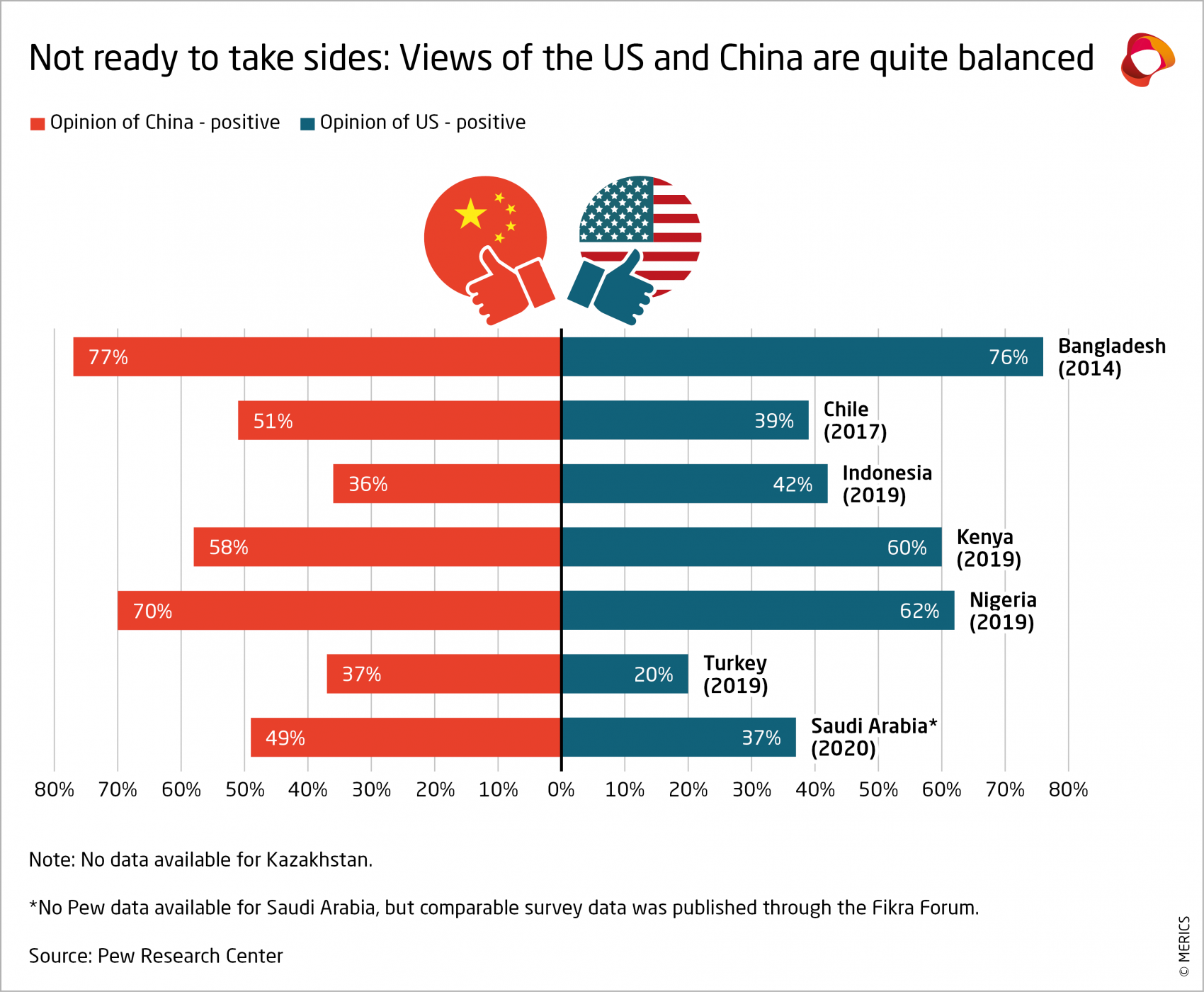

Attitudes towards China in the eight countries diverged widely from the mainstream narratives in developed liberal democracies; the same was true of attitudes to US-China tensions. There were several common trends among the eight, though key differences emerged too.

Economic ties with China have expanded in nearly all eight countries since 2012. Trade with China has grown significantly for most during the last decade. Overall volumes have risen by several multitudes for most, but the trend has brought sizable trade deficits with China for all except two – Chile and Saudi Arabia. Several countries saw imports skyrocket while their exports remained flat. Yet looking at overall trade with all partners, China now takes a much larger share of both imports and exports. It has become – for most – either the largest trading partner, or among the largest. Closer business ties, growing trade, and Chinese inbound investment were generally viewed positively, with some exceptions:

- Nigerian companies are concerned at how Chinese imports undercut prices and displace small producers.

- Large companies in Chile view China as an opportunity, but smaller companies struggle to compete, especially footwear producers.

Chinese financing and technical assistance in infrastructure projects was widespread in all eight countries and met with a largely positive reception. All the countries studied have signed on to the Belt and Road Initiative: all have railways, ports, airports, and other projects built by China’s national champions and funded by China’s banks. With some exceptions – Kenya and Kazakhstan – contributors reported limited concerns about the sustainability of debt with China, and the only one that invoked ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ – Turkey – was concerned about its neighbors falling prey, not itself. Beyond infrastructure investment and financing, there has been significant growth in investment in all eight countries; Chinese companies have established their operations, often at a staggering pace – another almost universally welcomed trend. However, some specific China-supported infrastructure projects and investments were viewed as concerning.

- In Kenya, Chinese firms brought in their own security forces and provided special training to Kenyan forces to protect the Standard Gauge Rail project between Nairobi and the port city of Mombasa. While cooperation went smoothly, there were local concerns that this undermined the Kenyan government’s role as sole security provider within its own jurisdiction.

- Rumors surrounding the possible relocation of 55 Chinese factories to Kazakhstan in 2019 triggered widespread anti-China protests; people demonstrated about the lack of transparency, pollution fears, rising debt levels and China’s mistreatment of Uyghurs and Kazakhs in Xinjiang.

In the security realm, China’s security relationship with most of the eight countries remains limited in scope, though it is expanding. Most of these countries have close defense and security ties with the United States, which they are interested in maintaining. Washington was seen as a more reliable security guarantor and – for some – arms provider. This was not true across the board, however. One country – Bangladesh – covered here counts China as its top arms supplier. And US withdrawal from international commitments under the Trump administration made others rethink their dependence on Washington and seek to strengthen security cooperation with Beijing.

- China has become Bangladesh’s main source of military equipment, making the country into China’s second largest arms export destination.

- Saudi Arabia has expressed concerns about the US wish to disentangle itself from Middle East conflicts, and has found a receptive audience in Beijing, which is reportedly now helping Riyadh build its own ballistic missiles.

Regional dynamics also play a key role in shaping how countries look at China and the opportunities and challenges posed by its growing influence. The importance of other regional players, and of tensions with neighboring countries cannot be overlooked in assessing how countries position themselves amid rising US-China competition.

- For Turkey, its relationship with Russia comes into play. A member of NATO, Turkey has firm security commitments to the Alliance that align it with the United States and Europe. However, Ankara’s close ties with Moscow and growing economic ties with Beijing, pull it in a different direction.

- Saudi Arabia’s main geopolitical concern is Iran’s role in the region which influences how it positions itself vis-à-vis China and the United States.

Countries that are in closer proximity to China also had concerns that would not trouble those far away.

- Indonesia has regular friction with China over conflicting claims to the South China Sea.

- Transboundary water management and land ownership issues play an important role in China-Kazakhstan relations.

Commonalities also emerged when looking at public perceptions of China across all countries in this study. Elite perceptions were universally improved by Beijing’s stance of non-interference in domestic politics, often in direct contrast to the conditionality the United States and Europe can impose on aid and investment. Political, military and business elites tend to see China in a positive light, focusing on opportunities in China’s large market and Beijing’s status as a possible counterbalance or alternative to the United States for smaller nations. This was true even among Muslim-majority countries included in the study; China’s crackdown in Xinjiang seemed to play little or no role for most, but not all, countries in shaping perceptions or policies. The general public also had a positive view of China across most countries, though the global Covid-19 pandemic seems to have worsened public opinion of China in many of them. Overall, China’s soft power has generally grown across most countries, but not in certain communities.

- Bangladesh has seen a growth in positive views of China in recent years, though the United States remains extremely popular due to factors like US vaccine donations and the sizeable Bangladeshi diaspora there, which feeds aspirations and sends remittance payments.

- Although five of the eight countries studied are majority-Muslim, plus Nigeria which is roughly half Muslim, only in two have concerns over the treatment of ethnic and religious minorities in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) had a meaningful impact at the political level.

- Turkey has a large Uyghur diaspora and the affinity of some Turks for their Uyghur brethren (Uyghurs are a Turkic people) has put pressure on various parties to raise the issue.

- Meanwhile, Kazakhstan shares a border with the XUAR, and both its native Kazakhs and Uyghurs have spoken out about Beijing’s mistreatment of their fellow ethnic Uyghurs and Kazakhs.

Overall, most countries had high hopes that closer ties with China would bring more opportunities to improve their economic footing and strengthen their geopolitical positioning. But those with the lowest GDP (PPP) per capita – Bangladesh, Kenya, and Nigeria – were more likely to show concern about the sustainability of trade deficits with China. This contrasts with sentiments in richer countries; like Chile, the only country to see a growing trade surplus with China thanks to commodities exports, and Saudi Arabia, which is seeking to invest part of its sovereign wealth fund in China and is considering pricing some oil exports in Chinese yuan.

Nearly all the countries covered follow a consciously pragmatic approach to US-China tensions. Prioritizing their own national interests, they try to avoid taking sides, preferring to take advantage of the contentious relationship between Washington and Beijing to extract deals and beneficial conditions from both. As long as this is a possibility, they will likely try to maintain this approach.