China and Russia: united in opposition

Beijing and Moscow’s bilateral communiqués have evolved in recent years to demonstrate the same threat perception, an analysis by Roderick Kefferpütz (text) and Vincent Brussee (data) shows.

Joint statements by China and Russia have over the last three decades shifted from an emphasis on rapprochement and economic development to employ a globalized and revisionist vocabulary under China’s party and state leader Xi Jinping. Our analysis shows China-Russia communiqués have since 2013 put global issues center stage and increasingly opposed the Western-dominated status quo, culminating in February’s declaration of a “friendship without limits” as “a new form of inter-state relations.” As Russia wages war against Ukraine, the world is looking to Beijing to see whether it might continue to support Russia. Our analysis suggests it will.

In February 1972, the United States and China signed the Shanghai Communiqué, reinforcing Beijing’s split from Moscow and altering the Cold War balance of power. But the 50th anniversary of the US-China rapprochement was this February overshadowed by another event. On the inaugural day of the Winter Olympics in Beijing on 4 February, China and Russia released a joint statement challenging the existing global order and proclaiming the beginning of a new era. Bilateral relations had entered “a new historical period,” Xi Jinping announced.

We used textual and semantic network analysis software to look back at three phases of recent Chinese history – the leadership of Jiang Zemin from 1993 to 2003, of Hu Jintao from 2003 to 2013, and of Xi since 2013. The data shows a steady deepening of engagement – and, under Xi, a major change in the terms associated with the relationship. Joint statements under Jiang paid attention to good neighborliness and border areas, those under Hu emphasized intensifying cooperation in economic development, often using keywords such as “investment,” “trade” and “energy.”

But under Xi China-Russia relations have adopted a much more “geopoliticized” language.

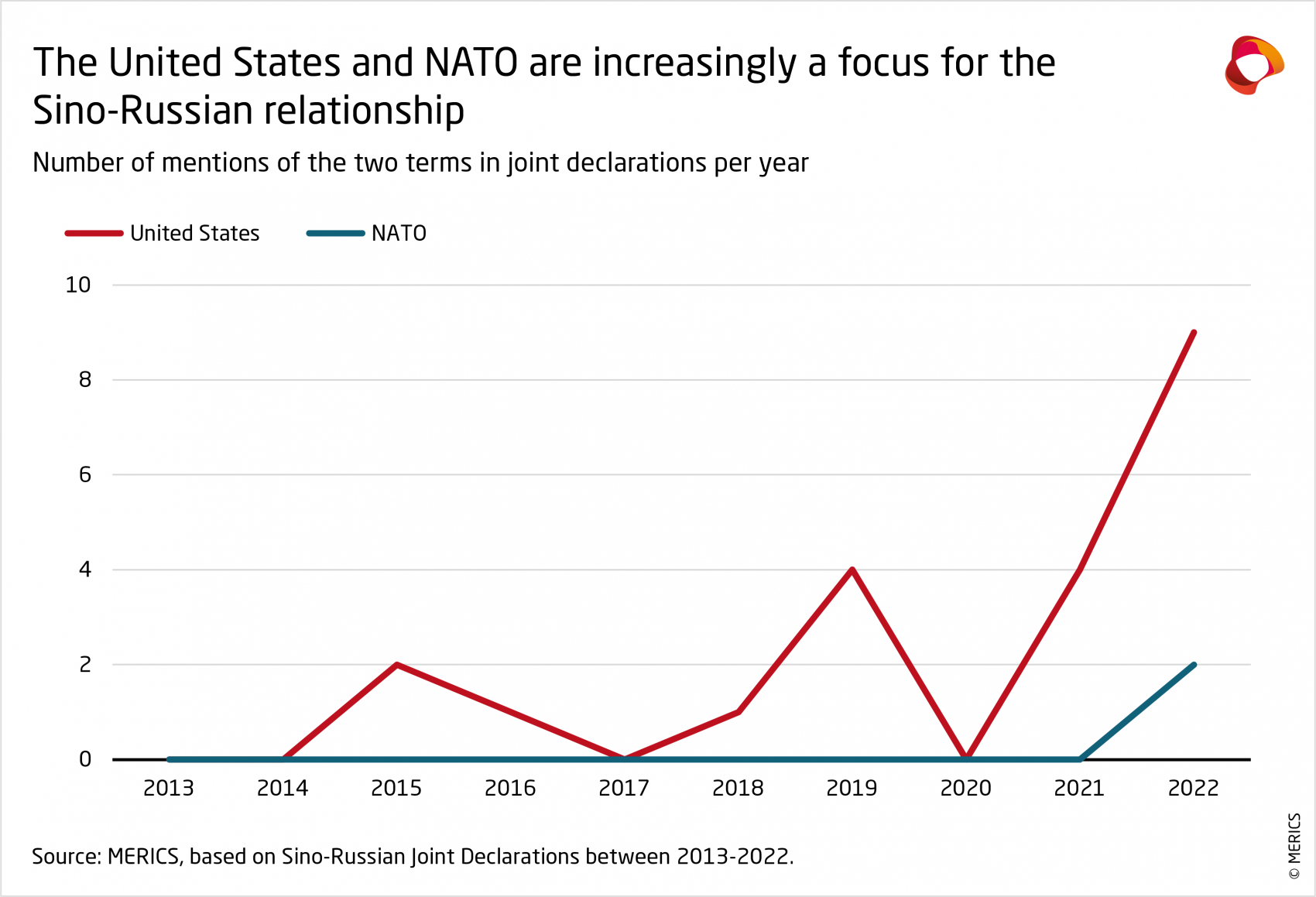

First, the US has become an increasing focal point of Sino-Russian joint statements. While mentions of the US in Chinese-Russian statements were negligible under Jiang and Hu, they have gained traction from 2014, leading to an all-time high with the 2022 joint statement (which additionally also singled out NATO for the first time; see exhibit 1). In this joint statement, both sides identified the US as a security threat in Europe and the Indo-Pacific.

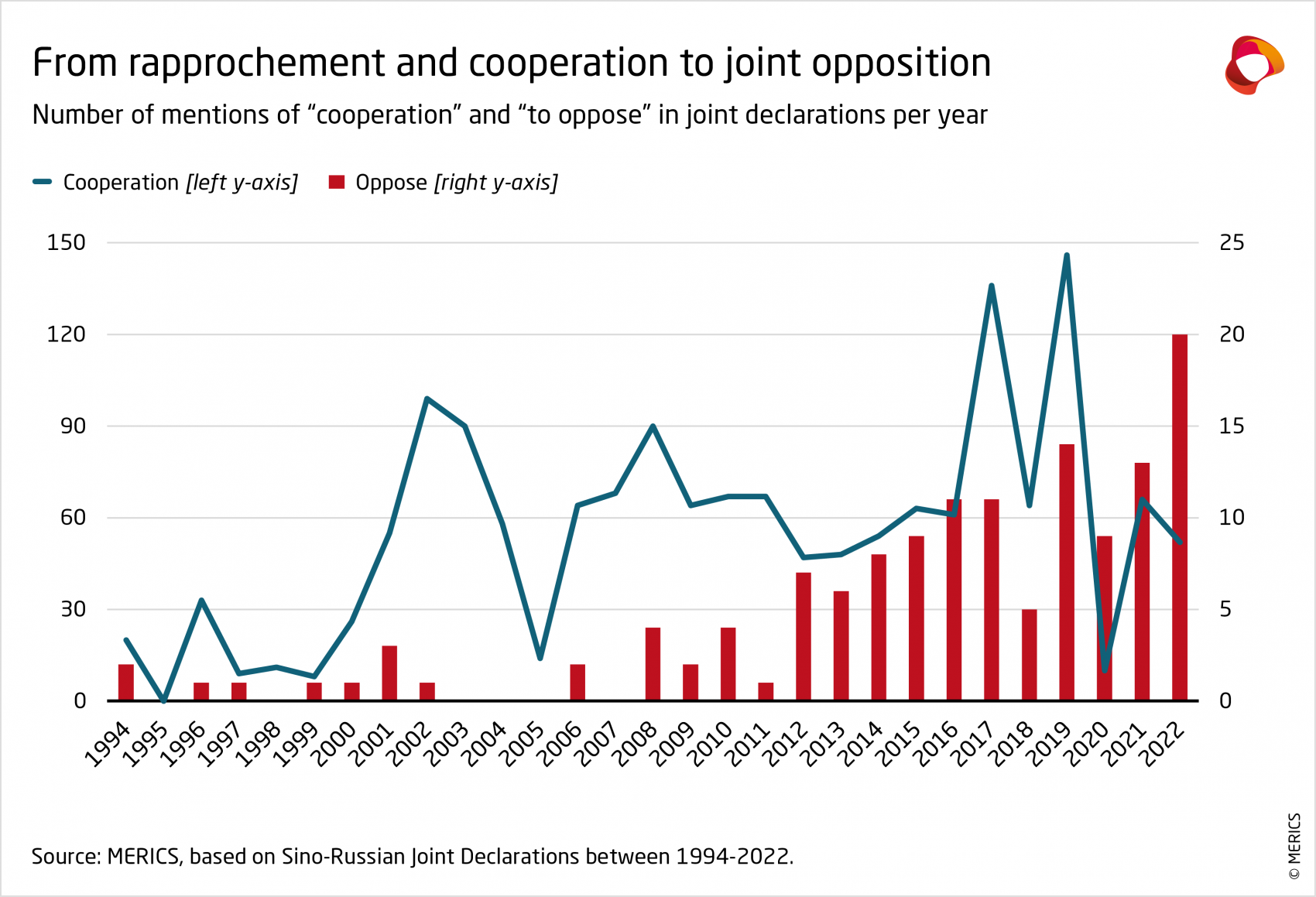

Second, the keyword “oppose” (反对) has gained decisive traction. This key term first came into heavy use in 2012, when it appeared seven times. It was used ever more in most years that followed, hitting a three-fold increase with 20 mentions in the 2022 joint statement. Interestingly, the word “cooperation” also reached a peak under Xi, in 2019, before returning to average levels in 2022 (see exhibit 2). This reflects increasing Sino-Russian cooperation.

But what do China and Russia actually oppose? The semantic network in exhibit 3 identifies the topical domains most closely related to their opposition: terrorism, unilateralism, subversion, interference in internal affairs and human rights. This constellation highlights that China and Russia increasingly have the same threat perception. They are looking at the world through the same lens ¬– and have a common understanding of how it should be ordered.

Third, there has been a marked increase in terms denoting geopolitical frontier areas, for example, “cyberspace” (+4,100%), “outer space” (+194%) and “Arctic,” a new entry. There has also been an increase in the use of the term “human rights” (+325%; see exhibit 4). China and Russia have over the years increased their cooperation about these issues. They have signed agreements on cyberspace (promoting the concept of cyber sovereignty), are planning to establish a joint lunar station, and have increased cooperation in the Arctic. At the same time, both have opposed international criticism of their deteriorating human rights records.

The data shows that China-Russia relations have shifted from focusing on bilateral political and economic relations to adopting a global perspective with obvious geopolitical ramifications. An increasing bilateral focus on the US, on opposition to things like unilateralism and internal interference, and on geopolitical frontiers, leads to two crucial insights.

On the one hand, the China-Russia relationship can be seen as defensive. Both regimes crave stability and strive to dominate their regions politically. They see regional actions of the US and its allies as security threats – and the democracy and human-rights agendas of the West as attempts to discredit them, impinge on their sovereignty and weaken their regimes.

In Chinese discourse, the China-Russia relationship is often described as a “back-to-back” strategic collaboration, denoting that both countries have each other’s backs. This is meant to free them from the necessity of military deployments on their shared 4,000-kilometer border – and allow them to jointly oppose the international order upheld by the US and the West.

At the same time, the China-Russia relationship can be seen as an offensive one. Both countries have started countering the West and wish to shape the future global order on their terms. They have increased cooperation in frontier areas where governance is yet to be cemented (cyberspace, outer space, the Arctic), and they are promoting their own versions of human rights and democracy – Russia talks about “sovereign democracy,” China about “whole-process people’s democracy.” Both are joining forces more and more to amplify their messages, engage in disinformation and counter Western-controlled narratives.

These changes have all come under Xi’s leadership, suggesting that the central aim of his Russia policy has been to join forces, oppose the US and its allies, and shape the global order according to Sino-Russian narratives, concepts and interests. It demonstrates how much the China-Russia relationship is shaped by personal dynamics. Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin are both authoritarian strongmen, who have tightened their grip on power over time. The fall of the Soviet Union has had a formative effect on both of them. Putin has called it the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century” and Xi sees it as a cautionary tale.

In 1972 Henry Kissinger, US President Richard Nixon’s National Security Advisor, was crucial in bringing the US and China together. In past years, there have been debates in Germany and the US about pursuing a “reverse Kissinger” to get Russia on their side against China. There are now hopes for a “Kissinger somersault” to win over China again to put pressure on Russia, especially as it is now waging war on Ukraine. Both are very unlikely scenarios, as our textual data analysis shows: China and Russia have come together under Xi, and their relationship looks set to continue being defined by their opposition to the US and the West.