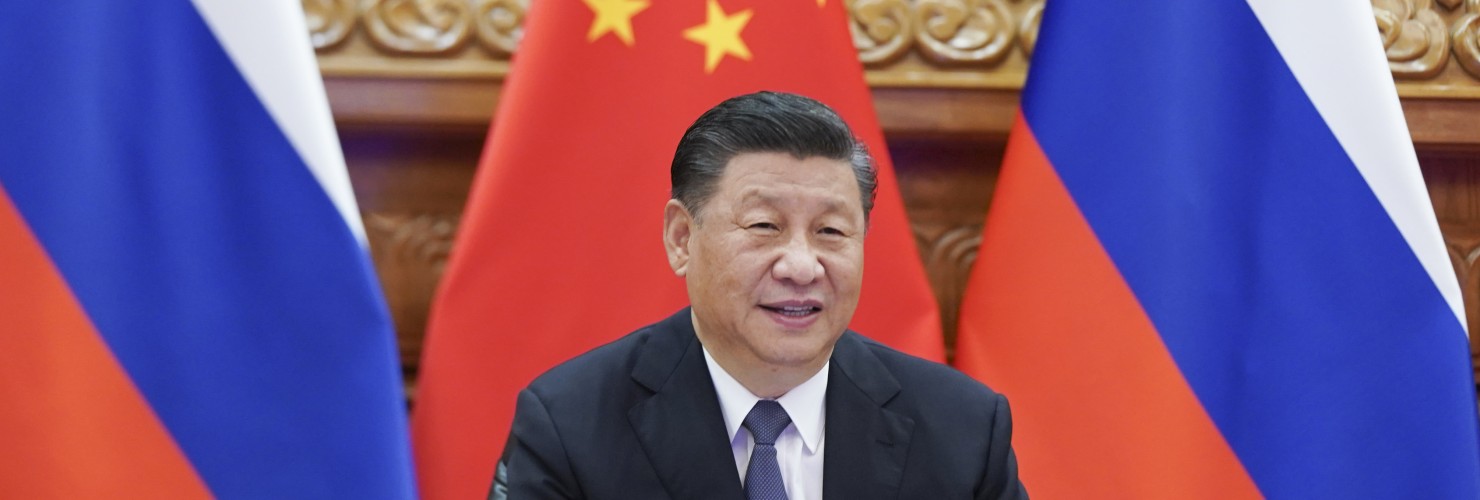

China opts for optimism in 2021 Russian security strategy reading

A startling feature of the Russian Federation’s recently released National Security Strategy is the palpable lowering of the status of China. The reaction from official PRC outlets has, however, been to praise the Strategy for its turn towards the Asia-Pacific. MERICS European China Policy Fellow Una Aleksandra Bērziņa-Čerenkova explores the motivations behind China’s optimistic reading of the document.

It is not until quite far on in the Russian Federation 2021 National Security Strategy (NSS) that China is first mentioned. In Clause 101, sub-clause 7, under Russian foreign policy goals, it states: “developing the relationship of comprehensive partnership and strategic interaction1 with the People’s Republic of China, special and privileged strategic partnership with the Republic of India, including for the creation in the Asia-Pacific region of reliable mechanisms for ensuring regional stability and security on a non-bloc basis.”

This formula is significantly humbler than the one in the previous Strategy of 2015. As Igor Denisov explains in his Diplomat article, “Cooperation with China is no longer seen as a ‘key factor in maintaining global and regional stability’ – at least, this is not emphasized publicly. The deletion of the ‘key factor’ formula, which featured in the two previous versions of the NSS, will have political implications, but it is premature as of now to measure the reach of this changed narrative.”

The Chinese reading: “strategic wisdom”?

The change in narrative naturally invites questions about China’s reaction to it. One might expect the Kremlin’s decision to downgrade China’s role, as well as to avoid adding Xi Jinping's signature phrase “for a New Era” in the official name of the partnership with the PRC, to be perceived in Beijing as a gesture of defiance. But official information outlets, including the state media, have been reluctant to highlight this point, focusing instead on the importance Asia plays in Russian strategic thinking.

An official website of the PRC’s Ministry of Justice, for example, offers the following interpretation: “While advancing the process of ‘de-Westernization’ and ‘de-dollarization’, Russia has listed China and India as the focus and priority of Russia’s foreign policy. The new version of the ‘National Security Strategy’ points out that Russia will continue to develop a “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership of Coordination” with China to jointly maintain peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific region.”

Meanwhile, the People’s Daily re-interprets the text altogether, giving China with a much greater role than the original grants it, and inserting the “New Era” phrase back in to the text: “Russia will continue to develop a comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination in the new era with China, jointly maintain peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific region, and continue to deepen cooperation with the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation member states and the BRICS.”

An article by Yang Sheng in the Global Times opens with, “Russia’s latest updated national security strategy shows that the US attempt to split China-Russia ties has failed again,” and goes on to frame the NSS as a continuation of the Russian pivot to Eurasia: “Chinese experts said the Russian leadership with strategic wisdom has found the influence and strength of the West is declining and that is why it is prioritizing ties with non-Western major powers like China and India.”

Not only are official Chinese outlets ignoring the PRC’s fall in the Russian priority list, but they are also trying to smooth it out, both for domestic and external audiences. The question is, why?

Different wording, similar understanding

Arguably, the gentle reaction of the PRC public media boils down to the fact that China finds the Russian position in line with its interests on three important points: standing up to the West, undermining the universality of liberalism, and no alliances.

First of all, no change in allegiance is perceptible in the NSS. Granted, Russia speaks about internal vulnerabilities more than before, but the list of outside forces that Russia sees as the primary challenges to its development has remained stable. They are the collective West – the United States in particular and NATO in general, perhaps with the addition of the transnational corporations: “The desire of Western countries to preserve their hegemony, the crisis of contemporary models and instruments of economic development, growing disproportions in the development of states, an increase in the level of social inequality, the desire of transnational corporations to limit the role of states are accompanied by an exacerbation of internal political problems, an increase in interstate contradictions, a weakening of the influence of international institutions and a decrease in the efficiency of the global security system.”

According to the Chinese reading, although Russia is much more self-oriented in this new document, it still ascribes a significant role to the PRC, and places it before the reference to India meaning, therefore, that it matters more.

As for the lack of reference to the “New Era”, the argument goes that since Russia is presenting itself as a strong force, it is understandable that it has avoided using the Chinese wording. No one understands this goal better than the country conceptualising “discursive power”. In fact, it is not the absence of the Chinese political discourse in this case, but rather its growing presence in other relationship-defining documents that has been flagged by Russian researchers. So, China can afford to let it slide occasionally.

Secondly, the NSS is actually beneficial to China’s value struggles. The Strategy states that “traditional Russian spiritual-moral and cultural-historical values are under active attacks by the United States and its allies”. For China the newfound call to strengthen the “traditional spiritual and moral foundations of the Russian society” echoes the strategy pursued by Beijing under Xi Jinping’s rule. The stress on homegrown standards in fact serves as an argument against the universality of liberal values. Even if Russia has left “the New Era” out of the text, it serves the general idea of Xi Jinping’s New Era quite well.

At the end of the day, China is quite comfortable with the “no block building” premise contained in the Russian NSS. If anything, China feels it has been saying the same thing for years with the three “no’s”: “international relations non-aligned, non-confrontational, and non-targeted against third parties”. The clear reference in the NSS to no block building shows that the view from Moscow is now more in line with Beijing than in earlier, more ambiguous statements by the Russian political establishment – for example, when, Vladimir Putin failed to exclude the possibility of an alliance.

Although the wording of the Russian NSS contains fewer references to China than the previous Strategy of 2015, its main messages do not go against China’s agenda – if anything, they serve it.

1 A direct translation of the Russian name of the relationship is used here.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily reflect those of the Mercator Institute for China Studies.