China wants to mend fences – and Europe must fend off menaces

Having failed to convince Europe of the benefits of its “neutrality” over Russia’s war on Ukraine, China now seems keen to point up the economic upside of good relations, says Alicja Bachulska.

China’s efforts to convince Europe that it is observing a well-intentioned “neutrality” in Russia’s war on Ukraine have had little success. But an economic charm offensive might be able to achieve what Beijing hasn’t in past months – convince leaders at least in some parts of European Union (EU) to return to some form of “business as usual”. As winter descends and war fatigue threatens to kick in, the EU could become more susceptible to the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) increasing efforts to normalize relations with European countries.

China has consistently opposed to economic sanctions of the type the US and Europe imposed on Russia, with a Foreign Ministry Spokesperson noting in February that sanctions of this type had in the past “caused serious difficulty to the economy […] of the countries concerned”. With the EU’s single market crucial for Chinese businesses and European states facing an energy crisis after years of overdependence on Russian gas, Beijing seems to see an opportunity to rejuvenate Europe’s shattered belief in “win-win cooperation” – the guiding principle of Germany’s relationship with Russia, once deemed to have made war impossible.

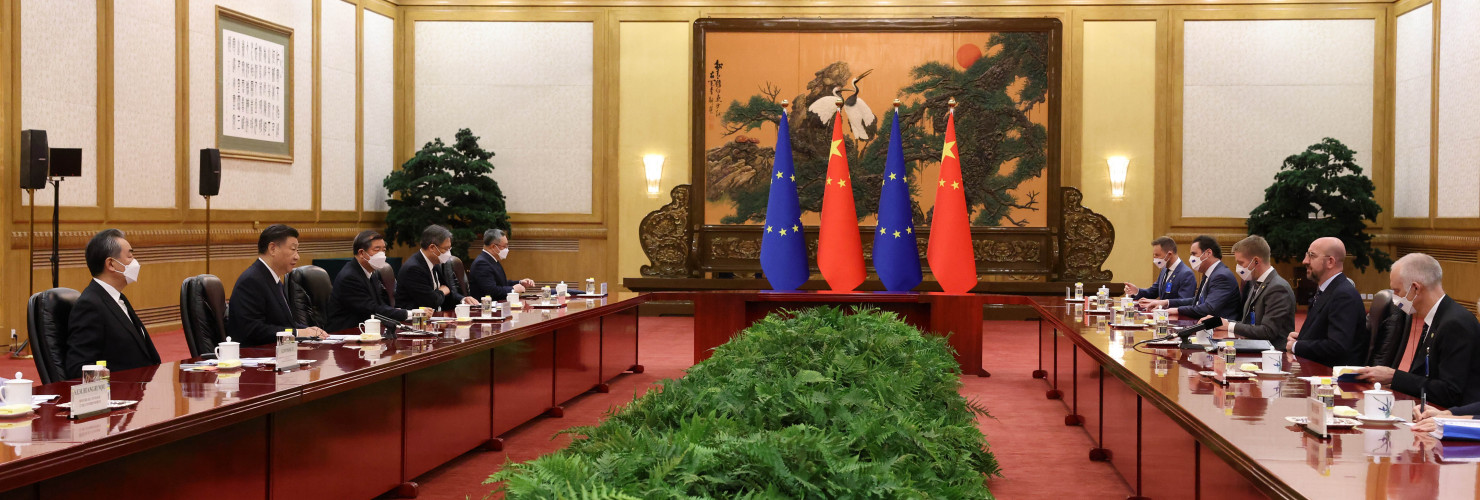

In an attempt to mend fences, Xi in November met in Beijing with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and then European Council President Charles Michel. Given the importance of economic relations with the world’s biggest economy, some observers asked whether Europe’s recently more assertive policy might soon be over. “China may view Scholz’s Germany as a weak link in a Western coalition,” policy analysts Fergus Hunter and Daria Impiombato from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute wrote in Foreign Policy magazine.

According to the Chinese readouts from Xi’s meeting with the German Chancellor, both sides expressed the need to “oppose attempts to politicize and weaponize exchanges in economy, trade, science and technology”. This was reference to many EU countries’ efforts to redefine their relations with China in the light of recent developments there – Xi’s continued centralisation of power and use of coercion to silence voices critical of the CCP. It was also an indirect rebuke of Washington, which in October had seen impose sweeping export controls to cut China off from advanced computer chips made with US tools anywhere in the world.

China has long sought to exploit Europe’s notion of “strategic autonomy” towards both Washington and Beijing, which the latter understands as the EU having to distance itself from strategic alignment with the US. In March, Wang Hongjian, the Chargé d'Affaires of the Chinese Mission to the EU, used a widely disseminated opinion piece to call on the EU to take “a strategic and long-term perspective and adopt a positive and pragmatic China policy”. A recent German opinion poll found that respondents were more wary of China – but that half wanted economic relations to continue at current levels or even become deeper still.

Given such ongoing receptiveness, it would not be surprising to see China increase its influence efforts in Europe in 2023. It could most efficiently do this by appealing to groups potentially most interested in moves towards a normalisation of economic ties. The most susceptible would be members of the businesses and political elites confident of their ability to balance short-term financial gain and a lived European “strategic autonomy” with the very real negative security implications of again tightening relations with China.

In counterpoint to protectionist noises from Washington, Beijing could even be tempted to again push for finalisation of the long-stalled Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), a deal blocked by the European Parliament in May 2021 after the EU and China got embroiled in a sanctions tit-for-tat over the situation of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Also, China’s media offensive will surely continue, with diplomats and state-affiliated media putting “more stability and positive energy” into EU-China relations, as China’s Mission to the EU has put it.

Europe has over decades internalized the notion of China as the world’s economic powerhouse. But given its goal of a “dual circulation” economy driven by domestic demand as much as exports, China could soon reach the limit of export-oriented growth. This makes unlikely any lasting return to the “win-win” relations of old, which saw Europe export high tech to and import cheap consumer goods from China. Instead of harking back to an outdated status quo, Europe needs a public debate about China's economy-related influence efforts and its record of economic coercion. It does not need to re-embrace this authoritarian regime.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily reflect those of the Mercator Institute for China Studies.