China’s social credit score – untangling myth from reality

The idea that China gives every citizen a “social credit score” continues to capture the horrified imagination of many. But it is more bogeyman than reality. Instead, we should be worrying about other, more invasive surveillance practices – and not just in China, argues MERICS analyst Vincent Brussee.

“What if every action that you took in your life was recorded in a score like it was a video game?” … “If your score drops to 950, you will be subject to re-education.” … “It is the beginning of slavery, complete control, and the disappearance of all freedoms ... In China, they call it social credit.” These are just some of the statements made in parliamentary debates in Europe and online commentaries about China’s Social Credit System. Given the vehemence of these views, and the attention they attract, it must have come as a real headscratcher to many when China recently pledged that would ban the use of AI for social scoring.

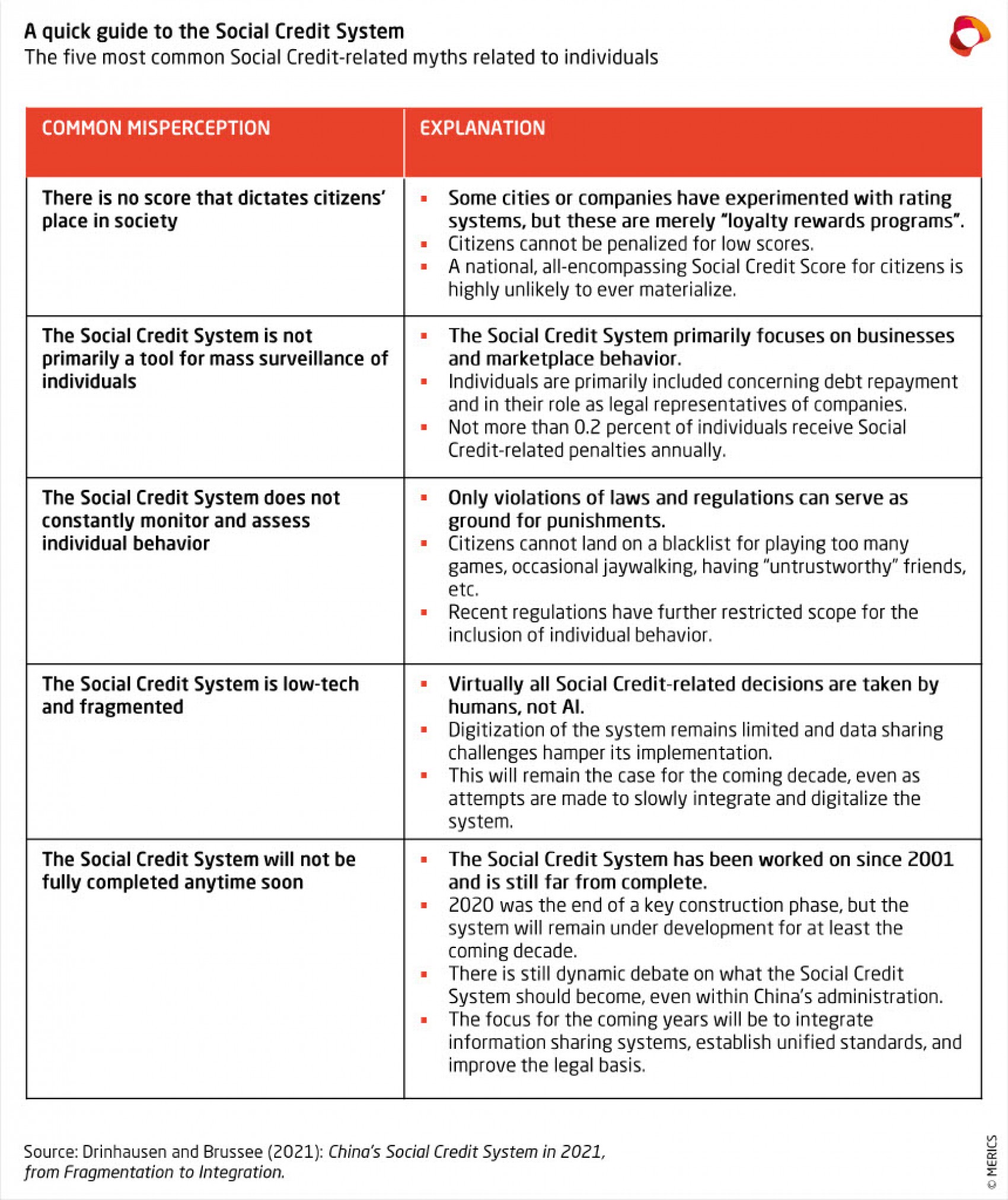

So, what are the facts relating to China’s Social Credit System (SoCS)? First, a system does exist, but it is very different from what is imagined by many critics outside China. The biggest disconnect is around the notion of scores. Some commentators seem to imagine that a magic algorithm draws from AI cameras and internet surveillance all over the country to calculate a score that determines everyone’s place in society. In reality, the SoCS is not the techno-dystopian nightmare we fear: it is lowly digitalized, highly fragmented, and primarily focuses on businesses. Most importantly, such a score simply does not exist.

Yet the myth still persists - even governments that acknowledge the complexities of the SoCS still express concerns about scoring and how it could be developed in the future. So, what is behind the idea of social credit scoring?

Provenance and early attempts

The SoCS, which first emerged in China in the early 2000s, was inspired by credit scoring practices elsewhere in the world, such as FICO in the United States and Schufa in Germany. In the main blueprints for the system there was no reference to large-scale scoring of individuals. It did, however, spawn tangentially-related initiatives like Alibaba’s Sesame Credit, but this was only indirectly related to the SoCS and, in any case, the People’s Bank of China eventually denied the company a credit license. Only in late 2016 did the State Council – China’s top governmental body – formally refer to the idea that it would “explore the establishment of a personal integrity score management system”.

From the early 2010s, some cities indeed started scoring pilots. However, these gradually became controversial – even in China. The city of Suining reportedly deducted points for government petitions and online comments, Suzhou planned penalties for reservation no-shows or cheating in online games, and Rongcheng for littering or jaywalking. Many of these pilots were later criticized by official media or failed to materialize. The most common critiques were that scores illegally restricted citizens’ legal rights or tracked behavior totally unrelated to the notion of “credit”.

Tried, tested, shut down

By 2019, China’s central authorities were stating explicitly that they were not happy with the idea. They issued formal clarifications that scores could not be used to penalize citizens and that only formal legal documents could serve as grounds for penalties. Pilot cities quickly followed suit: Wenzhou, having made ambitious plans in 2014, made a full 180 degrees and in 2019 released an encouragement-only scheme instead. Rongcheng issued a revision in 2021 that required voluntary application and could only issue rewards. Many other scoring plans never materialized at all.

The personal scoring initiatives that live on today serve only as positive incentives. Lacking teeth, they are essentially loyalty rewards programs like those operated by airlines, and few people make use of them. Further restrictions were formally rolled out in December 2021, curbing the types of behavior that can be included in the system. This is also why it is unlikely that a SoCS-superscore is yet to come: the authorities have tried something like it and found out it was not what they were looking for.

After all, why would Beijing develop such an all-encompassing system covering the entire population – the vast majority of whom are “well-behaved” – when they already have a wide array of covert tools with which they can suppress targeted groups of dissidents? Far more efficient.

Ratings are still of interest to the Chinese authorities where companies are concerned. In the coming three years, the State Administration for Market Regulation will start to classify companies on a scale from A to D nationwide. Companies in Zhejiang can already look up their “overall credit score”. However, these scores are not used to blacklist companies. Rather, they serve as an indicator of risk and are used to determine the intensity of supervision.

In any case, an over-engineered score that encompassed all one’s subjective actions would be so opaque as to be utterly worthless in practice. This is already visible today. Alibaba has the highest possible credit score in Zhejiang, in spite of its monopolistic behavior and scrutiny during the tech-crackdown.

The real risks of 21st century technology

All of this does not mean that the SoCS is benign. It also does not imply that China’s broader surveillance apparatus is a myth – quite to the contrary. However, public debates typically do not focus on these aspects. Rather, the interest in the system often stems from broader anxieties about digital technologies, as reflected in the UN pledge and similar actions taken by other countries. Often, the SoCS is merely invoked as a metaphor: either to depict some technological threat at home or to portray a techno-dystopian China.

This is symptomatic of a tendency to see China not as a real place with real people, but as an abstract “negative opposite” of “us”. While our discussions on tech in China remain overshadowed by largely fictional scoring, we ignore real threats of surveillance to exactly those people in China. And when we use the SoCS to invoke the image of a technological threat at home, we lose sight of potentially acute technological threats much closer to reality.

In both cases, the real losers are the people that those making the claims say they want to protect.