Hong Kong elections: Beijing redefines democracy

Beijing’s electoral reforms successfully shut out the opposition in last weekend’s elections in Hong Kong. Yet officials and state media insist that democracy has been improved. This is all part of the Chinese leadership’s broader push to master the global narrative around core values, says MERICS Senior Analyst, Katja Drinhausen.

Hong Kong has just been to the polls. Sunday’s vote for the new Legislative Council (LegCo) was the first since sweeping changes to the electoral system, introduced by Beijing in March 2021, came into effect. The 4.47 million eligible voters had a choice of 153 candidates, but there was little difference between them. At the last LegCo elections in 2016, candidates campaigned fiercely for a plurality of political positions, at times conflicting. This time, almost all of the incoming delegates belong to the pro-Beijing establishment.

This comes as no surprise. Over the past year, under the Hong Kong National Security Law the opposition camp has practically been dissolved. Over 50 former pro-democracy delegates and activists have been arrested and many of them are awaiting trial. Others have gone into exile or retreated from politics. A few have tried – unsuccessfully it seems – to carve out a moderate centrist position and refocus on livelihood issues. Faced with a lack of choice, voter turnout reached a historic low, with just over 30 percent casting their ballot, down by almost half since the last election.

Undeterred, Chinese state media described a city gripped by “election enthusiasm”, claiming the electoral revamp had improved democracy and good governance in Hong Kong. China’s State Council issued a white paper on democratic progress in Hong Kong the day after to further drive home the message, lauding the efforts of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) for providing constant support to Hong Kong in developing its democratic system.

Democracy without opposition

The Chinese leadership’s desire to rewrite the rules of democracy in Hong Kong was driven by fears that opposition candidates might get the upper hand after their landslide victory in 2019’s district council elections. High turnout at unofficial pro-democracy primaries further spooked the central government in July 2020. Held just days after the Hong Kong National Security Law came into effect, citizens seemed ready to support candidates with clear demands for universal suffrage and local autonomy. Shortly after, the LegCo elections were postponed for a year. While officially due to Covid, this also gave the Chinese leadership time to introduce its fundamental overhaul of Hong Kong’s election system.

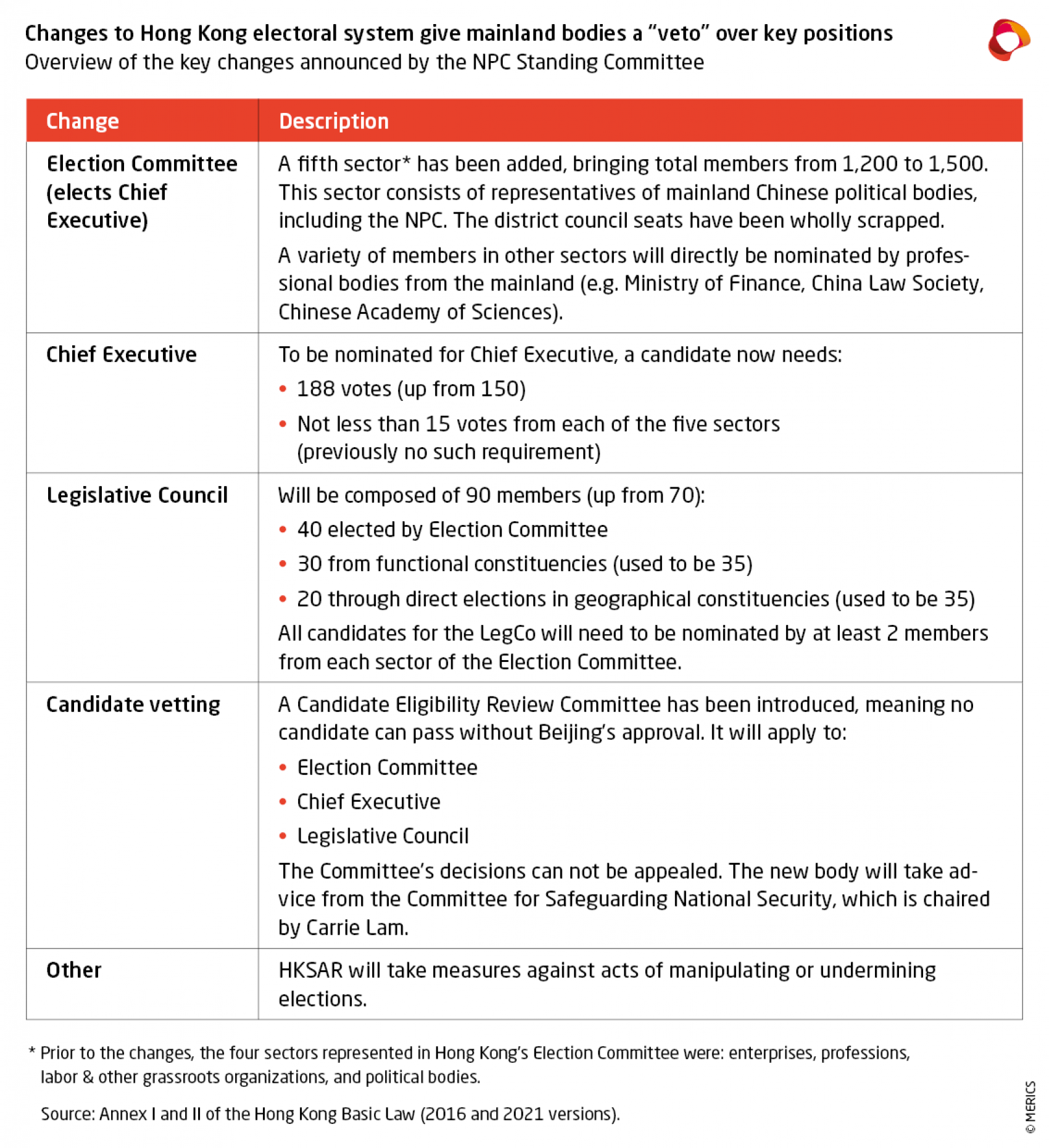

The majority of Hong Kong’s citizens just don’t vote the way Beijing wants. The electoral reforms (see table) were therefore designed to restrict representation of their preferences. Candidates are now required to be “patriotic” and thereby also supportive of strengthened CCP rule over Hong Kong. To enforce this, each prospective candidate is checked by a screening committee in collaboration with the national security department of the police. In addition, the weighting given to direct citizen votes was lowered. Before the electoral reform, votes from geographical constituencies determined half of the 70 LegCo seats. Under the newly changed composition, it is now merely 20 out of 90 seats.

Beijing achieved its goal. In 2016, 29 out of 70 LegCo seats went to pan-democrats. In 2021, 89 out of 90 delegates are pro-Beijing establishment – with one sole moderate member in the mix. Nonetheless, Hong Kong government officials have fiercely defended the diversity and outcome of the elections. But their focus was on diversity of age, social backgrounds and agenda points, not opposing political views. John Lee Ka-chiu, Hong Kong’s Chief Secretary for Administration, said: “This election is neither ‘monotonic’ nor ‘homogenous’ with candidates coming from different political spectrums”, but added that, “under the common vision of patriots, those elected will no longer be traitors who dedicate themselves to resisting the central government and the mainland or colluding with external forces”.

The Hong Kong government and party-state media came down hard on any insinuation that citizens weren’t happy with the newly curated selection of candidates. Calls for a boycott or casting invalid votes were treated as a criminal offense, with 10 people arrested and warrants issued for activists in exile. The Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, that had quite accurately predicted the low voter turnout, was attacked by state media for trying to “hijack society” and for having polls that “align with forces that are anti-China and disrupting Hong Kong”. The Hong Kong government also sent out letters to domestic and international media outlets over “incorrect” coverage of the election, chillingly emphasizing the extraterritorial effect of Hong Kong’s national security legislation.

A global struggle for narrative power

The struggle over defining what democracy looks like in Hong Kong is not just about keeping up appearances. It is closely connected to the party-state’s broader push for discourse power and reflects the new ambition to shape global narratives around democracy and other core values. Both China’s new white paper on democracy (“China: Democracy that Works”), which was released ahead of the US-led Democracy Summit, as well as the new white paper for Hong Kong argue that democracy is not about representation of conflicting political positions and direct participation. Rather it is about “whether the people of the country are satisfied and happy,” as China’s foreign minister Wang Yi phrased it. The changes in Hong Kong are meant to align with this view, where democracy is focused on the delivery of public goods and improving livelihoods by the state, not on the exercise of individual civil and political rights.

The recent white papers aren’t an isolated push. They are the culmination of years of domestic “discourse system construction” to integrate and define terms such as democracy and human rights in a way that is compatible with CCP doctrine. Xi has firmly claimed democracy as a socialist core value and declared China the most efficient democracy in the world. Especially since the party’s 100th anniversary this year, Chinese state media have published a flurry of English language statements extolling the virtues of China’s democracy as the superior political system, while Western-style liberal democracy has been described as a threat to the world.

This signifies a new stage of ambition: following Xi’s command, China’s effort to gain global discourse power has now become a mission to gain global narrative power. Whereas in the past state media argued that democracy could come in many shapes and forms – essentially telling liberal democracies to stop hogging the term – now they argue that China should step in and foster a “correct view” of democracy, or “true democracy”, as it was framed at an official symposium on the LegCo elections.

If you redefine norms, you don’t have to change behavior

The new white paper on democracy in Hong Kong states that, “the people of China have always yearned for democracy, and the CCP has always stayed true to the mission of delivering their dream”. But by restricting freedom of the press and assembly, and increasing control over the judiciary, academia and civil society, the central leadership and Hong Kong’s government are dismantling key pillars of liberal democracy. When they remove memorials and books about the student protests in 1989 from universities and public libraries, when they ban vigils for Tiananmen and sentence activists for participating, and when even Simpsons episodes are preemptively censored, they are also trying to erase alternative discourses and memories of what else “democracy” could mean in China.

The motivation is simple: if China’s own brand of top-down party-state democracy can mobilize domestic and international support, the danger posed by “wrong” ideas of liberal democracy will surely fade. More importantly, by reshaping global norms and debates on democracy, Beijing hopes to contain international criticism of its practices and ultimately legitimize them. After all, if the world is convinced what you are doing is right, you don’t have to change your behavior