As Hong Kong rebels, why is Macau so quiet?

President Xi has recently been promoting Macau as the posterboy for China's “One Country, Two Systems” principle. He may be hoping that Hong Kong's citizens will heed his call, but this seems unlikely for the differences between the two Special Administrative Regions (SARs) are huge.

On a visit to Macau last month to mark the 20th anniversary of the city’s return to China, President Xi Jinping used the opportunity to heap praise on the former Portuguese colony for implementing the “One Country, Two Systems” principle “fully and accurately”—in other words, for demonstrating fealty to Beijing and exhibiting strong patriotic values. Indeed, while many in Hong Kong – China’s other SAR – regularly defy the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) various encroachments and call for democracy, Macau has remained remarkably silent. What’s more, many in Macau are critical of the recent protests in Hong Kong. Clearly implicit in Mr Xi’s address was a call to Hong Kong to learn from its neighbor.

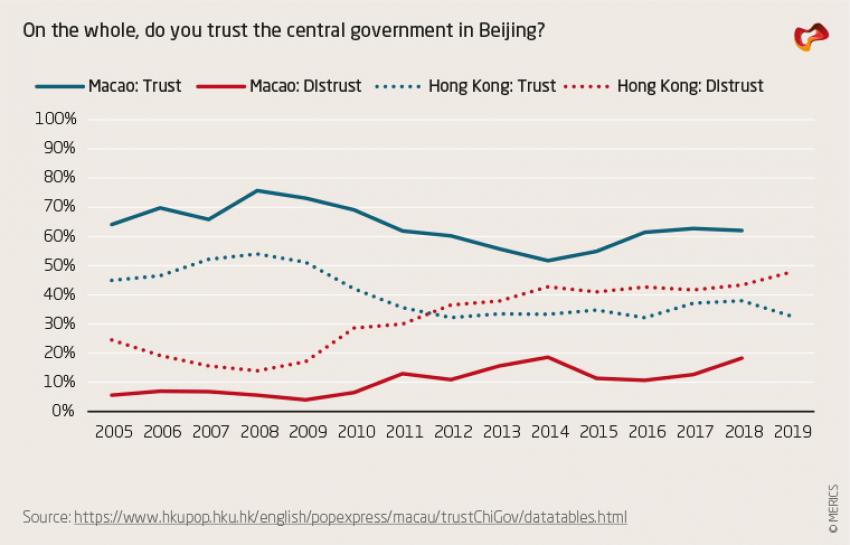

It seems unlikely, however, that Hongkongers will comply. Too much distinguishes the two SARs from one another: Unlike Hong Kong, pro-CCP groups have controlled and influenced Macau for over half a century. What's more, Macau’s citizens not only identify more strongly with the PRC but are also more trusting of Beijing.

One reason may have to do with wealth. Since its handover in 1999, Macau’s GDP per capita (at purchasing power parity) has more than quadrupled to USD 122,435 in 2018—nearly double that of Hong Kong and seven times that of the rest of China. Now flush with years of bumper budget surpluses, its government provides yearly cash hand-outs of around USD 1,250 to its permanent residents. This does not mean that all Macau residents are rich: wealth inequality is high. But they are much better off on the whole than their mainland compatriots, who, along with Hong Kong, endure a far greater wealth gap.

Unlike Hong Kong, Macau trusts Beijing

Not only has Beijing enabled Macau to prosper, it is also regarded by many in the city as more competent than their own local government. While the latter has been plagued by scandals from corruption to mismanagement of public works, the former has proven very responsive to Macau’s needs. From kick-starting the city’s gambling industry boom, to allowing extensions of its miniature land mass (33 km2 compared with 1,107 km2 for Hong Kong) and territorial waters, policies from Beijing have been welcomed warmly. Macau’s citizens know all too well how much their success depends on the central government.

Identity also plays a key role. While Macau’s citizens identify as much with the PRC as with Macau itself, local identity in the former Portuguese colony remains underdeveloped. Like Hongkongers, people in Macau speak Cantonese as their first language and still use traditional Chinese characters in writing. But unlike its neighbor, Macau has a tiny population of just 680,000 and has neither had an acclaimed cultural industry nor a unified education system to help foster a strong sense of collective identity. As a result, its citizens tend to use both Hong Kong and the mainland as cultural reference points.

Despite four and a half centuries of Luso-rule, a mere 2 percent of the population can actually speak Portuguese and only around a quarter English (compared with over half in Hong Kong). This certainly limits people’s exposure to western and perhaps more liberal influences. Although the Portuguese language is still very evident in Macau, be it on street signs or official documents, people’s identification with their colonial past remains weak. People do take pride in their civil liberties but, unlike Hongkongers, are less intent on safeguarding their already wavering rule of law. More strikingly perhaps, most have no qualms about singing the PRC’s national anthem and speaking Mandarin.

The emergence of a distinct local identity has also been hampered by Macau’s gradual “mainlandization”. In 2016, almost half (43.6%) of its citizens were born in mainland China, slightly more than those born in Macau itself (40.7%). In comparison, less than a third (29.8%) of Hong Kong’s 7.3 million residents were born on the mainland. Exposure to mainland tourists is also much greater in Macau than in Hong Kong. Last year over 25 million mainlanders visited the city. As a result, the proportion of fluent Mandarin speakers in Macau has surged from 24 percent in 2006 to over 50 percent today. Since the handover, forces pushing towards greater social and economic integration with the mainland have been growing ever stronger.

Unlike Hong Kong, pro-Beijing groups have controlled Macau for over half a century

Last but not least, Macau’s closeness and deference to Beijing can only be understood in the light of its recent colonial past. In December 1966, at the height of Mao’s Cultural Revolution, a violent clash broke out between the Portuguese and pro-Communist Chinese groups. The so-called “123 Incident” marked the effective end of Portugal’s rule over Macau. Soon after, the Portuguese authorities acknowledged the PRC’s sovereignty over the colony and banned pro-Kuomintang groups from the region. In Hong Kong, by contrast, the British succeeded in quelling a similar uprising at around the same time, which side-lined the Communist sympathizers there for good.

From then on, groups loyal to the CCP took control of nearly all aspects of Macau’s economy, politics and society. Unlike the institutions in British Hong Kong, those in Macau were weak and more vulnerable to political interference. Indeed, until 1974, Portugal was itself an authoritarian state. Subsequent Portuguese governments appeared more concerned by domestic affairs and their relations with China than pushing for extensive democratic reforms in their Chinese colony. In contrast to Hong Kong, Macau never enjoyed a strong rule of law and was never promised universal suffrage.

To this day, pro-establishment groups continue to dominate affairs in Macau. Whereas in Hong Kong the press still strives to act as a pillar of democracy, in Macau the Chinese-language media is mostly government-funded and more restrained by political pressures and self-censorship. To add to these constraints, Macau’s very size further discourages dissonant voices from emerging. Unlike Hong Kong, social circles in Macau are relatively small and incestuous. Its citizens are therefore much more averse to confronting the establishment for fear of putting their careers and businesses at risk.

Macau is undoubtedly a freer place than most parts of China, but the CCP’s grip on it has always been much stronger than in Hong Kong.

For all these reasons, if Mr Xi wishes to promote Macau as a model for the “One Country, Two Systems” principle, so be it. But if he thinks that Hong Kong can be compared with Macau and is likely to learn from it, he is most certainly mistaken.