‘Made in China’ electric vehicles could turn Sino-EU trade on its head

Europe is now the main target for electric vehicle exports from China - a trend that has benefited greatly from Chinese market-distorting policies. Given the serious implications this could have for the European economy, the EU needs to carefully monitor the situation at home and abroad and consider the use of trade defense instruments of its own. By Gregor Sebastian and François Chimits

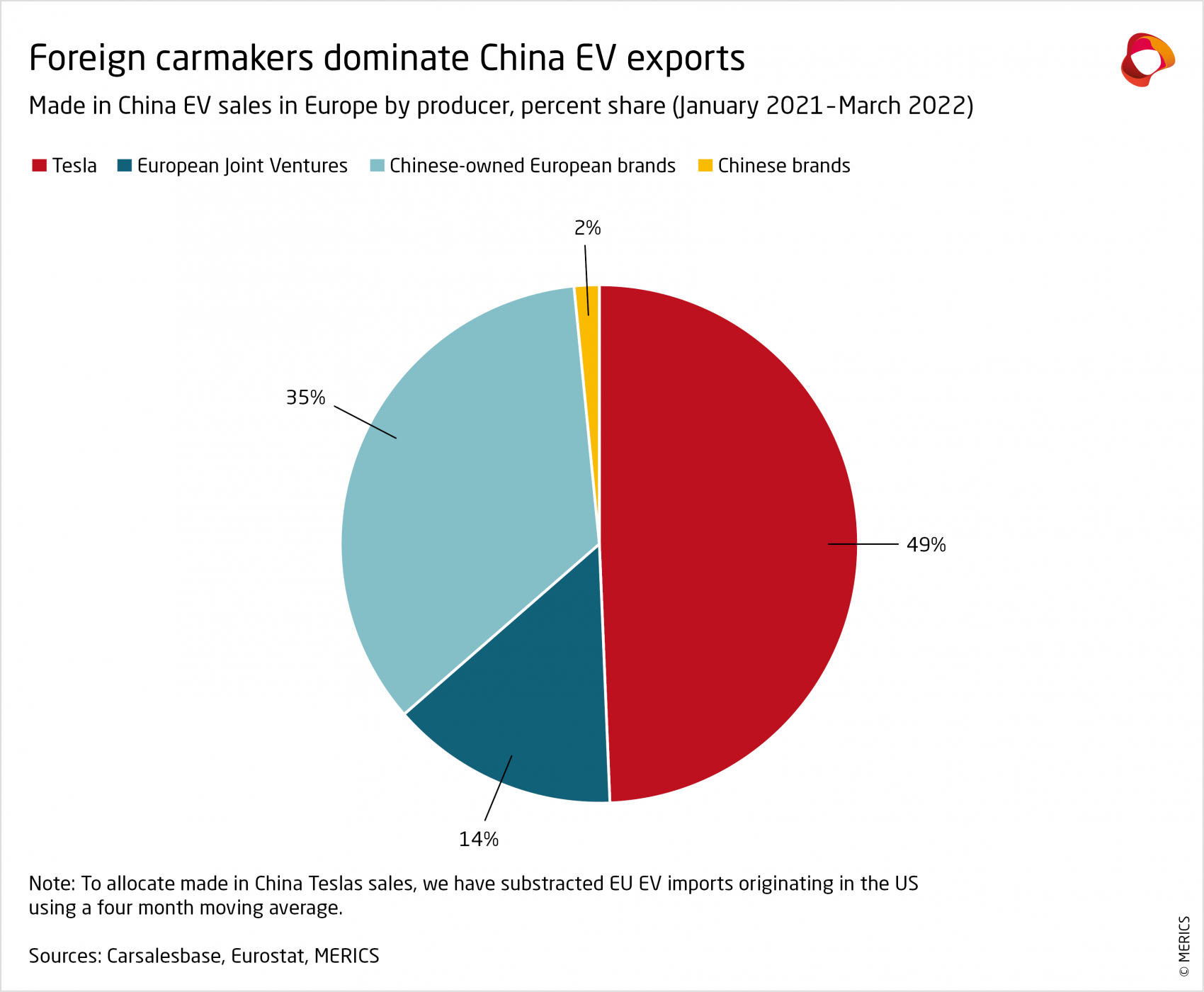

Europe has become the primary destination for ‘Made in China’ electric vehicles (EVs). In 2021, China’s global EV exports more than doubled to 555,041 units on the back of booming production capacity. Around 40 percent of this was absorbed by Europe, where Chinese EV already make up ten percent of total EV sales.

Crucially for Europe, Chinese EV exports to the EU have not grown because the cars are better but because European and US carmakers are switching to producing EVs in China, including for the European market. As market access has loosened, they have ramped up investment. Renault’s Dacia Spring as well as the iconic Smart and Mini EVs by Daimler BMW will be developed and produced in China for global markets.

And China’s strong export growth is set to continue as more firms announce export plans and Beijing phases out purchasing subsidies – a move that will slow domestic demand. Against this backdrop, Europe is a particularly attractive target due to its currently low trade barriers, well-developed charging network and high EV purchasing subsidies that can also be used for imports.

China’s strong EV export growth has considerable implications for Europe’s economy

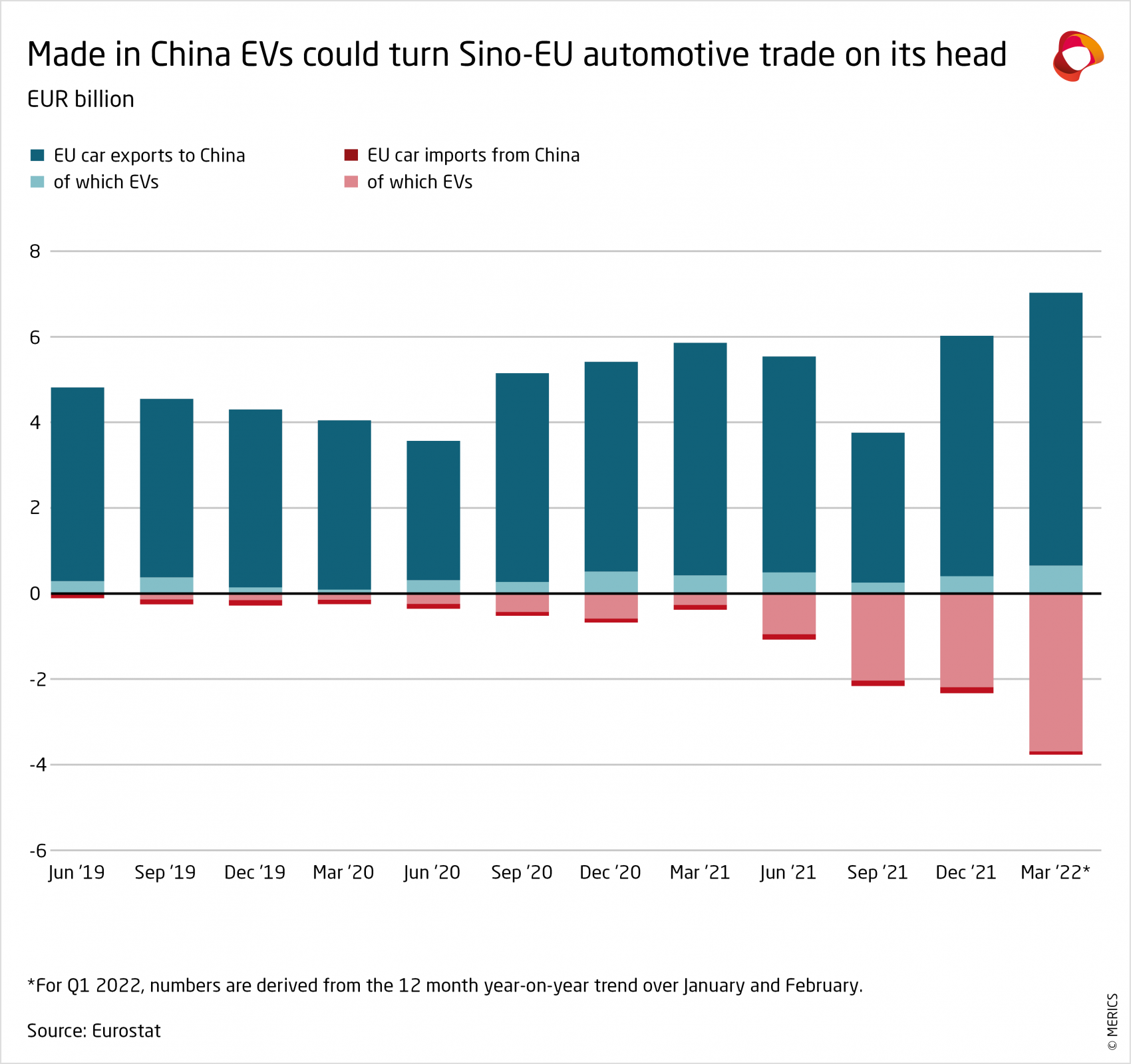

China-made EVs could turn Sino-EU automotive trade on its head. In EV trade – the future mainstay of the auto sector – the EU is quickly becoming a net consumer of China-made vehicles. On top of that, if European carmakers use China as an export hub for third markets, this will mean less production in Europe.

This has serious implications for Europe’s industrial heartlands because the automobile sector has long been one of the main European exports – to China and third markets. In 2019, it made up ten percent of EU exports and a third of the EU trade surplus. The sector also accounts for seven percent of Europe’s GDP and ten percent of manufacturing jobs (2019). This highlights that China-made vehicles put European employment, investment and innovation at stake.

Furthermore, the European automotive industry is geographically highly integrated, with a third of any member state’s production being provided by other member states. So, it’s not only the large exporters like Germany that would be at risk. In addition, vibrant domestic EV production is a requirement for sustaining an electric battery industry – a key sector in the EU’s industrial plan to fix strategic vulnerability.

China’s advantage gained through subsidies and restricted market access

The rise of China’s EV sector is closely linked to a number of industrial policy measures. To spur the development of a domestic EV industry the government has combined handing out subsidies with restricting market access for foreign-made cars and batteries. This means that ‘made in China’ global EV exports – which are likely to increase over coming years – pose a challenge to market-based competition.

Three industrial policy measures have particularly distorted the market:

- China tied purchasing subsidies to local production, which itself was conditioned on the transfer of core EV technologies to Chinese competitors, effectively shutting out foreign EV makers, such as General Motors, that would prefer to export to China.

- China excluded foreign battery companies from its domestic market to help domestic firms to move up the value chain. EV batteries are the most valuable part of EVs, accounting for 35 to 50 percent of value added. In 2015, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology tied the handout of purchasing subsidies to a list of approved battery producers. Even though Japanese and South Korean companies were market leaders at the time, only Chinese battery makers made it on the list and became suppliers of Chinese and foreign OEMs. Although the list was abolished in 2019, today, six out of the ten biggest battery producers are Chinese and the biggest, CATL, commands a global market share of 32.6 percent.

- Central and local governments provide cheap capital resources, for example, through local government investment funds, and inputs such as electricity and land as well as speedy licenses and approval processes for China-based producers. These include Chinese startups such as NIO and Xpeng but also foreign producers like Tesla and BMW. In contrast to nationality-based subsidies, which hurt foreign workers and investors alike, such location-based support is particularly harmful to foreign workers.

The dynamics in China require a European response

The shift in trade relations in the automotive sector underpinned by China’s industrial policy marks a fundamental turning point in EU-China relations – one that requires a European response. Foreign carmakers’ deep entanglement and investments in China are strengthening China’s own EV and battery tech capabilities and will potentially foster strong competitors for Europe’s homegrown industry. While corporations look at declining market shares in China, the EU needs to grapple with long term impact on its industrial base at home.

To address these challenges, the EU could consider the use of trade defense instruments (TDI) even if their implementation is currently still viewed critically and considered unrealistic by market players, many of whom would be directly impacted by such measure. EVs from China are only taxed at ten percent duty, well below the United States’ 27.5 percent tariff (hiked in 2018) on Chinese cars. China-based EV exporters not only enjoy low trade barriers into Europe, they are also able to make use of European purchase subsidies since these are – unlike in China – unrelated to the origin of the product.

The use of TDI would send a strong signal that even France and Germany would not shy away from an assertive European response to Chinese distortions. It would also play into the Commission’s and the EU Parliament’s plan to deal with Chinese industrial policies that are potentially harmful to the European single market. However, such posturing has been met with skepticism in smaller member states. They fear that such EU actions prioritize the interests of France and Germany. But as Slovakia, Poland and Romania are heavily involved in the European automobile value-chain, the use of TDI would benefit them too.

By taking a stance on Chinese industrial policies on EV, the EU would signal its ability and willingness to bear economic costs to pursue broader ambitions and long-term interest. This would show European producers that the EU is unwilling to put up with having its market flooded by subsidized exports from China.

EU action against ‘made in China’ EVs could spark significant turbulence in already strained EU-China relations. However, the EU’s solar industry –another key sector for Europe’s green transition – serves as a reminder of the high costs of inaction: it is now dominated by Chinese producers thanks to a long history of distortive practices.