Strategic rivalry with China and Biden’s transatlantic promise

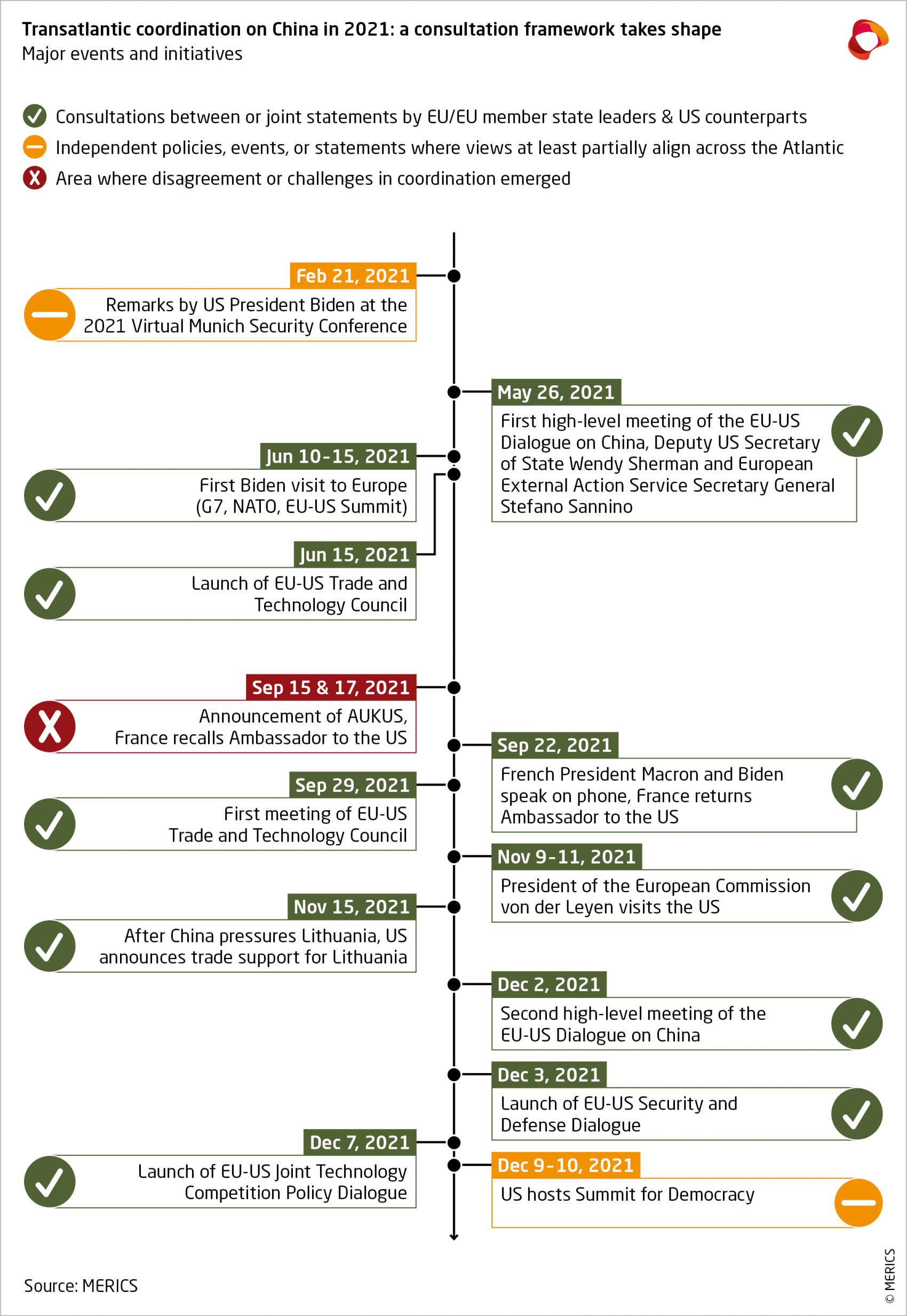

High-level dialogues brought new life to transatlantic China-policy coordination during President Joe Biden’s first year in office. But Michael Laha says EU-US collaboration is still a work in progress.

One year since Joe Biden became US president, the revitalized US-European partnership he invoked as a counterweight to a rising China is having a rough time – in hindsight, maybe that was foreseeable. “The transatlantic alliance is back,” Joe Biden said at the Virtual Munich Security Conference last February, before warning about “stiff” competition with China. Two years earlier, Biden pointed out, he had made a promise that the US would return to the alliance-friendly approach Europe was used to from the Obama administration.

Biden’s co-panelists were not convinced. The Trump presidency had left an enduring sense of unease about the trajectory of the US partnership. Germany’s then Chancellor Angela Merkel warned the US and Europe did not always have the same priorities, and French President Emmanuel Macron asserted the need for Europe to act more independently from the US – Europe needed to be more “strategically autonomous.”

Both sides, however, recognized that they needed to take advantage of what promised to be a relatively collaborative period in transatlantic relations, to work out persisting differences, including on issues related to China. In order to focus on the latter, the two sides met twice under the umbrella of the EU-US Dialogue on China, a format originally announced with the Trump administration.

Convergence on China is harder to come by than Americans and Europeans had hoped

A crisscrossing fabric of new high-level dialogues covering technology, trade, and security also involve consideration of China, even if the country was not explicitly mentioned in the stream of press statements that have followed the meetings launching these initiatives. But a closer look at these exchanges reveals that transatlantic convergence on China is harder to come by than Americans and Europeans had hoped. Vastly different regulatory approaches to technology and trade and a strengthening conviction in Europe that it needs to be more independent in defense and security policy will continue to weigh on transatlantic coordination on China.

One of the most important new initiatives is the EU-US Trade and Technology Council (TTC), which first met in September 2021 and set up 10 working groups to discuss technology standards, supply-chain security, investment screening and other issues.

The TTC is not the first transatlantic trade dialogue – there have been a variety of similar efforts at least since the 90s. However, this time, Europeans and Americans were brought together by a broadly shared understanding that their two markets needed to fortify against assertive autocracies such as China – Rebecca Arcesati has highlighted the multitude of risks associated with many Chinese technologies and pointed to the need for a transatlantic alternative. But questions on whether the US and Europe can forge a transatlantic convergence on technology have already emerged.

The US had hoped to use its Summit for Democracy in December to announce the “Alliance for the Future of the Internet,” a project aimed at developing an alternative to internet governance being championed by China, which in recent years has made significant strides in defining data and internet regulation that is friendly to its authoritarian form of government. The proposed internet alliance is meant to cover several issues also being looked at in TTC working groups and the EU-US Joint Technology Competition Policy Dialogue. As observers have pointed out, the field of projects aimed at fostering safe and values-based technology use is getting crowded.

The White House ended up delaying the launch in part due to pushback by American civil society groups. The initiative had also generated skepticism among officials from Europe about Washington’s appetite for actually implementing digital rule-making. Rather than regulating them, the US has more or less left big tech companies to their own devices. Europe, meanwhile, has rolled out a regular stream of laws and rules, starting with a landmark data-privacy law and now moving on to the Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act. The US Department of Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo swiftly criticized these two new pieces of European legislation, suggesting they would ultimately do more to hurt American companies than put an end to Chinese abuses.

Coercive trade moves by China will put EU-US co-operation to the test

In the broader area of trade, the US and EU managed to work out major disputes to smooth the way for closer collaboration. They resolved a quarrel about tariffs on steel and aluminum imposed during the Trump administration and the Airbus-Boeing subsidy dispute that had dragged on for 17 years. However, coercive trade moves by China will put this new EU-US co-operation to the test: After Lithuania allowed Taiwan to set up a representative office and China imposed trade barriers, Washington extended trade support straight to Lithuania. An opportunity for the US to join forces on the issue with Brussels may have been stymied by the EU’s own failure to respond quickly and strongly.

This and other problems highlight the importance of getting communications across the Atlantic right. To prepare the US for “serious competition with China,” Biden hurried the withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan, catching European allies by surprise. Only weeks later, the US launched an initiative to support partners in the Indo-Pacific who are facing an increasingly aggressive Chinese military posture in the region. AUKUS is a deal involving the transfer of nuclear submarine technology between the US, UK, and Australia. After it was announced, European officials began to ask themselves whether their voices on defense mattered at all.

French President Macron, whose pre-existing submarine deal with Australia was rendered void as a result of AUKUS, was so aghast that he recalled his ambassador to the US. To heal the rift, President Biden affirmed his support for European defense, a cornerstone of an emerging European “strategic autonomy” championed by Marcon. The EU is looking to set up its own defense just as the new US ambassador to NATO, Julie Smith, is calling for the over-half-a-century-old alliance to be retooled for the challenges posed by China. But as Helena Legarda has pointed out, it is far from certain that NATO members will be able to align on China.

To fortify a close EU-US alignment within NATO, both sides announced the EU-US Security and Defense Dialogue, which will convene for the first time in the course of this year.

The year 2022 will likely reveal whether this new fabric is sturdy enough to deliver on the promise of a closer transatlantic partnership on China.