MERICS China Security and Risk Tracker

01/2022

Focus Topic

“Strategic stalemate”: 2022 will be a difficult year for China

In 2022, the party will set the tone and direction of China’s domestic and international policy for years to come. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will hold its 20th Congress in the fall, when President Xi Jinping seems certain to secure a third term as party secretary and state president. Ahead of the congress, the CCP will be consumed by domestic policy and internal political jockeying and will want to prevent any major instability from disrupting its plans for the year. However, from Beijing’s perspective, the international environment remains challenging.

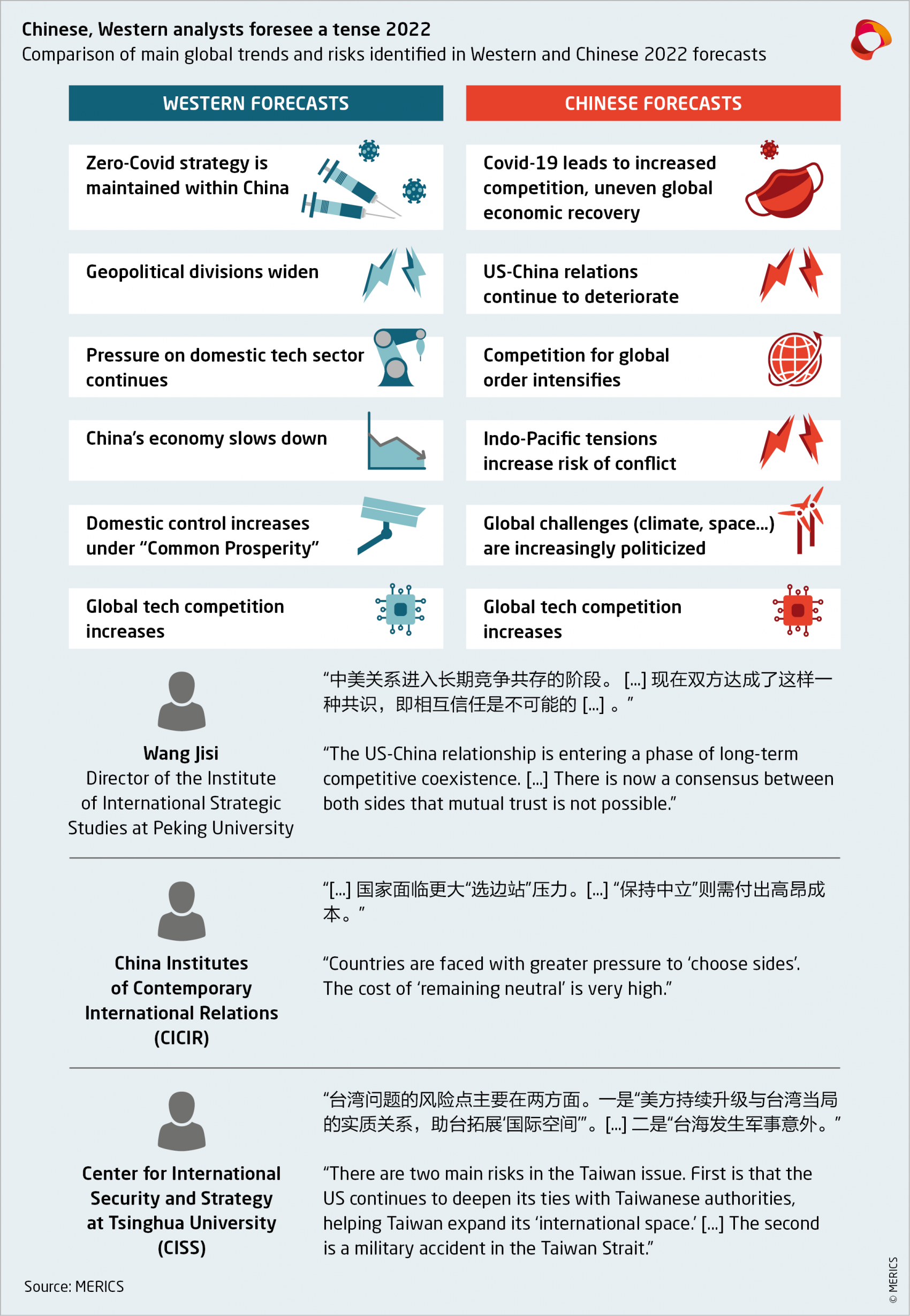

Among the main global trends predicted for 2022, Western analysts and forecasters such as the Economist, Control Risks or Eurasia Group have warned of greater decoupling and geopolitical tensions with China, as discussed in a previous piece by Roderick Kefferpütz, published on February 15.1 Here, we build a fuller picture of the year ahead by examining 2022 forecasts from two Chinese organizations – the Ministry of State Security-affiliated China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations (CICIR)2 and the Center for International Security and Strategy (CISS) at Tsinghua University.3

Their analyses are essential to understand how top Chinese foreign policy thinkers see the world, as this will contribute to Beijing’s priority setting in the coming months. They can show us those issues where cooperation may well be possible, and those where it will be difficult.

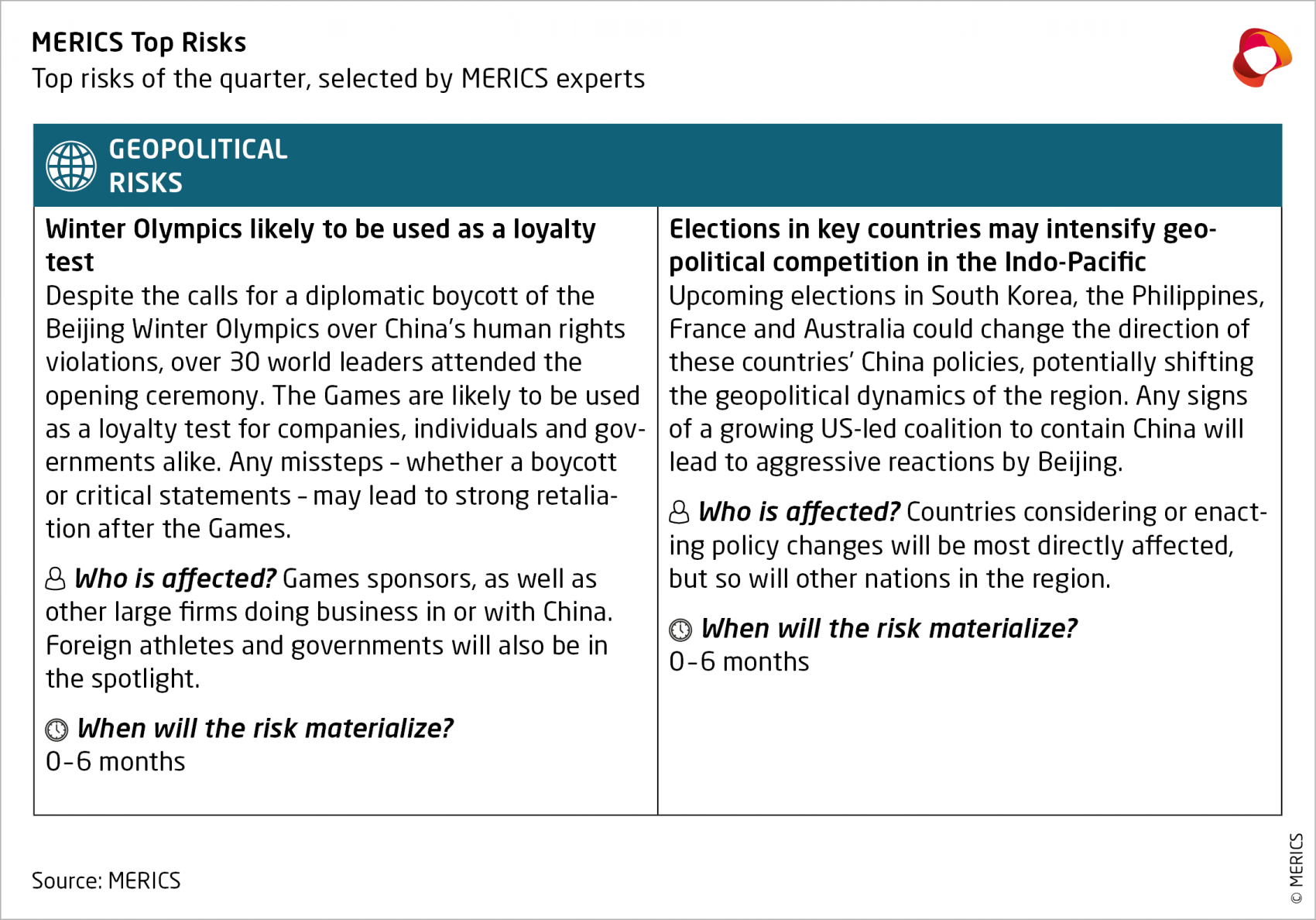

Geopolitical competition will increase, amid US-China stalemate

The picture that emerges from these two forecasts is of a difficult international environment for China. Both agree that 2022 will see yet more intense geopolitical competition. Both put US-China tensions at the heart of the risks Beijing faces this year.

Beijing seems intent on bringing relations between the two countries (now both superpowers) back on track, or at least “de-icing” them, as a way to reduce risks and prevent escalation that would destabilize China in the run-up to the party congress. Nonetheless, the language Chinese experts use to refer to the relationship between the two has changed. They now refer to relations with Washington as having entered a state of “strategic stalemate” (战略相持). The phrase is reminiscent of Mao’s discussions about fighting “protracted wars,” and signals a degree of perceived equality between the two powers. China and the US will have to find a way to coexist and manage their competition, as neither side has the upper hand, as yet.

Neither of the two Chinese forecasts expect open conflict in 2022. However, accidental escalation remains a distinct possibility, especially in the South China Sea or along the border with India. CISS cites the reappearance of frictions around China’s borders as its top risk for 2022. Interestingly, the situation in the Taiwan Strait, is seen as relatively less uncertain, with the aggravation of tensions in the Strait appearing lower on the list of 2022 risks. This largely reflects Beijing’s lack of interest in triggering a conflict there in 2022. To be sure, Taiwan is still seen as a problematic issue, especially given the growing wave of Western support for the island. The US, in particular, is accused of using “salami-slicing” tactics over Taiwan, a phrase that adapts Western language on China’s behavior in the South China Sea. An accidental crash between PLA and US military planes or vessels around Taiwan is seen as the likeliest scenario that could trigger a crisis in the Strait.

Chinese experts also worry about US efforts to build regional coalitions to confront the challenges posed by China. This is seen as a thinly disguised attempt to contain China’s rise. The Quad, AUKUS and the recently announced Japan-Australia defense agreement are named as clear examples of this trend. China’s experts warn that the Biden administration may shift its focus this year towards “co-opting” developing countries and making them choose sides, given it has already secured buy-in from traditional partners. We can therefore expect greater Chinese attention towards precisely these countries, as Beijing tries to outcompete Washington for influence. Africa, Southeast Asia and the Middle East – all regions along the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – will most likely top the priority list.

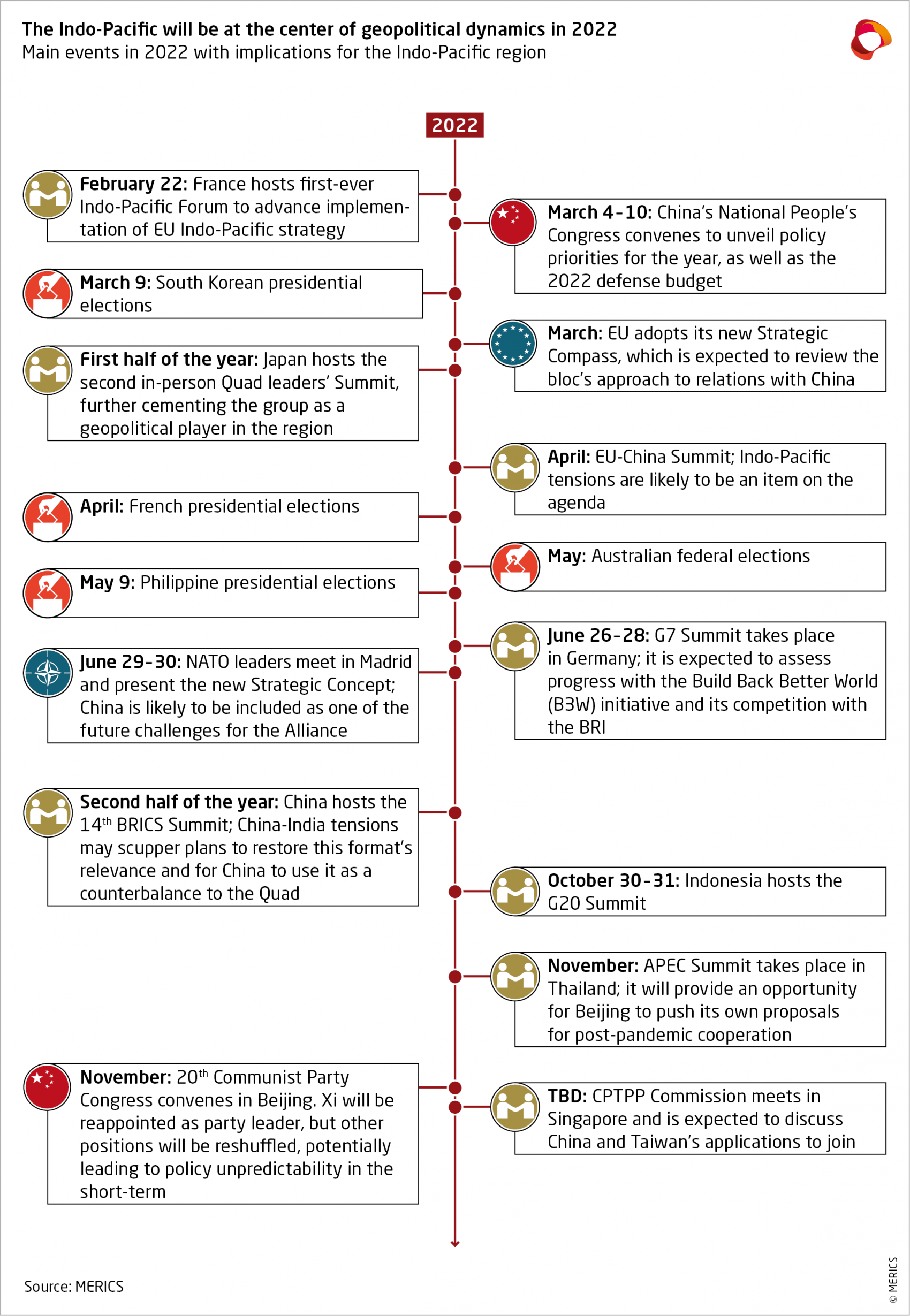

There is also a sharper focus on the importance of the Indo-Pacific for China’s security and its stake in the overall political situation in the region, and also along the Belt and Road. Among the main sources of uncertainty and risk in 2022, CICIR experts list the politics of Afghanistan, Iraq and Myanmar; slow progress in the Iran nuclear deal talks; and ongoing Russia-Ukraine tensions. As a result, upcoming elections in such key countries as Australia, South Korea, the Philippines, France or the United States have taken on new importance.

Finally, the two forecasts predict China’s external economic environment will become more difficult in 2022. They anticipate continued US sanctions on Chinese firms and individuals; plus new European instruments to tackle unfair competition with China; and growing transatlantic cooperation on these issues. CISS also highlights access to resources as a potential, underdiscussed, risk. Rising oil prices, alongside China’s deteriorating relations with major raw materials exporters like Australia could threaten China’s energy security this year.

Global challenges require cooperation with the West though frictions are high

The Covid-19 pandemic and the ensuing global economic recovery feature prominently in the forecasts considered here. They predict global tensions stemming from unequal access to vaccines and other medical equipment. Emerging and developing markets are expected to struggle to make a full recovery this year, further deepening global inequalities. The trends could impact global supply chains, and lead to instability and crisis in affected countries.

Chinese analysts predict Western efforts to “politicize” global challenges will increase in 2022. For instance, while the effects of climate change are recognized as a pressing issue, they call out the EU for imposing new, unfair trade barriers on the pretext of tackling global warming, specifically its new carbon border adjustment mechanism.

Chinese experts are aware that cooperation with the West is essential to tackle all these global issues. All the forecasts examined propose some joint solutions, such as a – presumably China-led – joint international task force to prevent future pandemics. They also highlight the key role that Chinese initiatives could play, when expanded to the rest of the world, in solving common challenges. President Xi’s ‘Global Development Initiative’, for example, is put forward as a way to guarantee stable development for developing countries in post-pandemic times. At the core of this approach is Beijing’s ambition to shape the global order in its image.

The way forward: China’s priorities in 2022

China faces a difficult year as it prepares for the 20th Party Congress. The party will have to find a balance between preventing instability, and projecting strength domestically and internationally.

The two sets of forecasts examined outline what they assess will be the way forward for Beijing in 2022. According to them, China will emphasize managing competition with the West to prevent escalation, rather than seeking co-operation. They advocate securing buy-in from other countries for China’s approach to the global order, especially in the Global South, and for China to make progress in its quest to become a leader in global tech governance. Foreign Minister Wang Yi echoed this approach in his review of his ministry’s foreign policy priorities for 2022.4 The policy areas and issues to watch this year therefore are:

- Leading the fight against the Covid-19 pandemic: China will continue to promote the Global Vaccine Cooperation Action Initiative proposed by President Xi at the G20 summit in October 2021, and will push for the formation of an international task force to work on the prevention of future pandemics.

- Expanding narrative control ahead of the party congress: Beijing will concentrate its efforts on “telling China’s story well”5 and on defusing any external risks and challenges before they fully materialize. We should therefore expect China to be even more proactive and aggressive this year with any issues it feels threaten the party’s bottom line.

- Reforming the global governance system: Beijing will take advantage of the multiple multilateral events taking place in Asia in 2022, namely the BRICS, APEC, G20 and SCO summits, to try to promote its own views of the global order and to secure buy-in from other countries.

- Deepening global partnerships and de-icing relations with the US: besides strengthening strategic cooperation with Russia and trying to control the risk of escalation in the US-China relationship, this year will see Beijing try to push the EU to go back to a model of relations based on cooperation, instead of rivalry. Beyond that, the focus will be on deepening ties with developing nations by presenting China as a reliable partner that is willing to support their decisions to prioritize development interests over human rights, unlike Western countries.

- Defending China’s core interests: China should be expected to push back even more aggressively against any attempts to infringe on China’s “sovereignty, security and development interests”. Countries, businesses or individuals whose behavior is deemed to be an attack against these interests should expect swift retaliation.

- Supporting China’s domestic economic development: the BRI will remain one of the main instruments for China to maintain economic growth rates and stable supply chains. Beijing will also turn its focus towards implementing or concluding new free trade agreements in 2022. In particular, negotiations with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states, and Japan and South Korea, are likely to receive a boost.

Although Beijing will mainly focus on domestic issues this year, its international policy efforts will be directed towards the areas outlined above. Efforts will be made to reduce tensions in the top risk areas, but it would be unwise to take such efforts as a sign of permanent shifts in policy direction. The CCP is simply out to ensure that nothing disrupts preparations for the 20th Party Congress.

Key Developments of the quarter

Domestic Stability

Zero-Covid strategy, regulatory crackdown come with costs

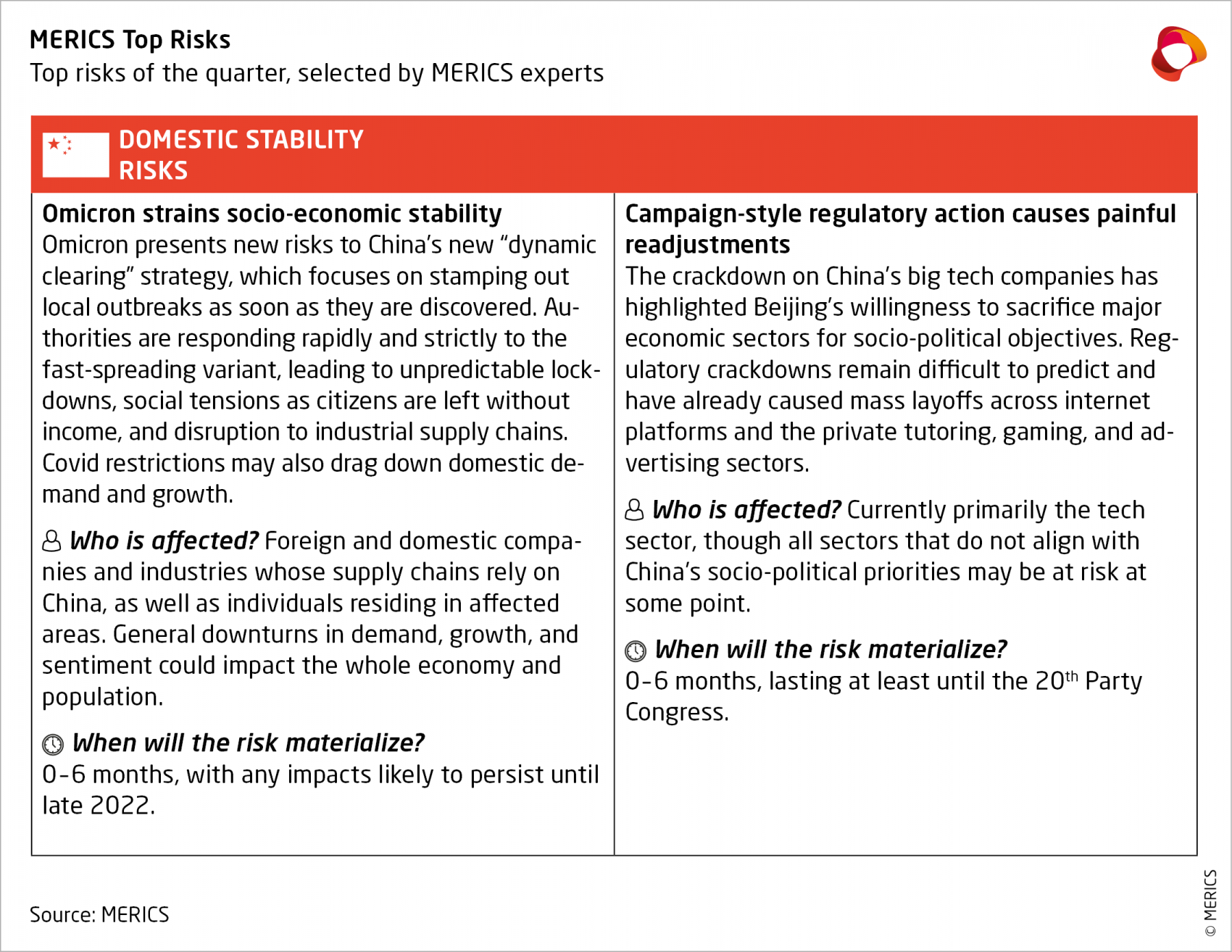

China’s local lockdowns spread and gathered pace under the pressure of ever more infectious Covid-19 variants. In Xi’an, 13 million people were locked down for 33 days starting on December 22, 2021. China’s first Omicron outbreaks swiftly followed, triggering local lockdowns in Tianjin and some parts of Beijing in January. The authorities’ swift actions have impacted individuals, local businesses, and the supply chains found in these major cities.

On balance, China’s new “dynamic clearing” strategy, which recognizes the system’s inability to prevent cases from appearing and instead calls for local governments to stamp out local outbreaks as soon as possible, remains a success. It minimizes deaths and ensures daily life carries on in most of China largely as normal, so China’s leaders are unlikely to change tack anytime soon. However, increasingly regular local outbreaks are producing heightened socio-economic risks throughout China. The hard containment approach has caused protests as migrant workers and other low-income groups have been left without income. However, an alternative policy of relaxed measures would be far more dangerous. China’s health system would struggle to cope with a big influx of cases, especially in less developed regions.

China’s continuing regulatory crackdown is exacerbating socio-economic risks too. Like the zero-Covid strategy, it is meant to bolster stability long-term. Paradoxically, the blunt campaign-style actions first escalate instability. Crackdowns on homegrown Big Tech and the debt-burdened real estate sector have led to mass layoffs at affected firms. The popular, privately-owned after-school tutoring sector has fallen out of political favor, and been shut down altogether. President Xi has signaled that the regime will not shy away from socio-economic costs emanating from regulatory actions if the outcomes support party-state objectives. It is possible that more campaign-like regulatory moves lie ahead in the run-up to the party congress in November 2022.

Security and Defense

The Indo-Pacific remains the main arena of competition

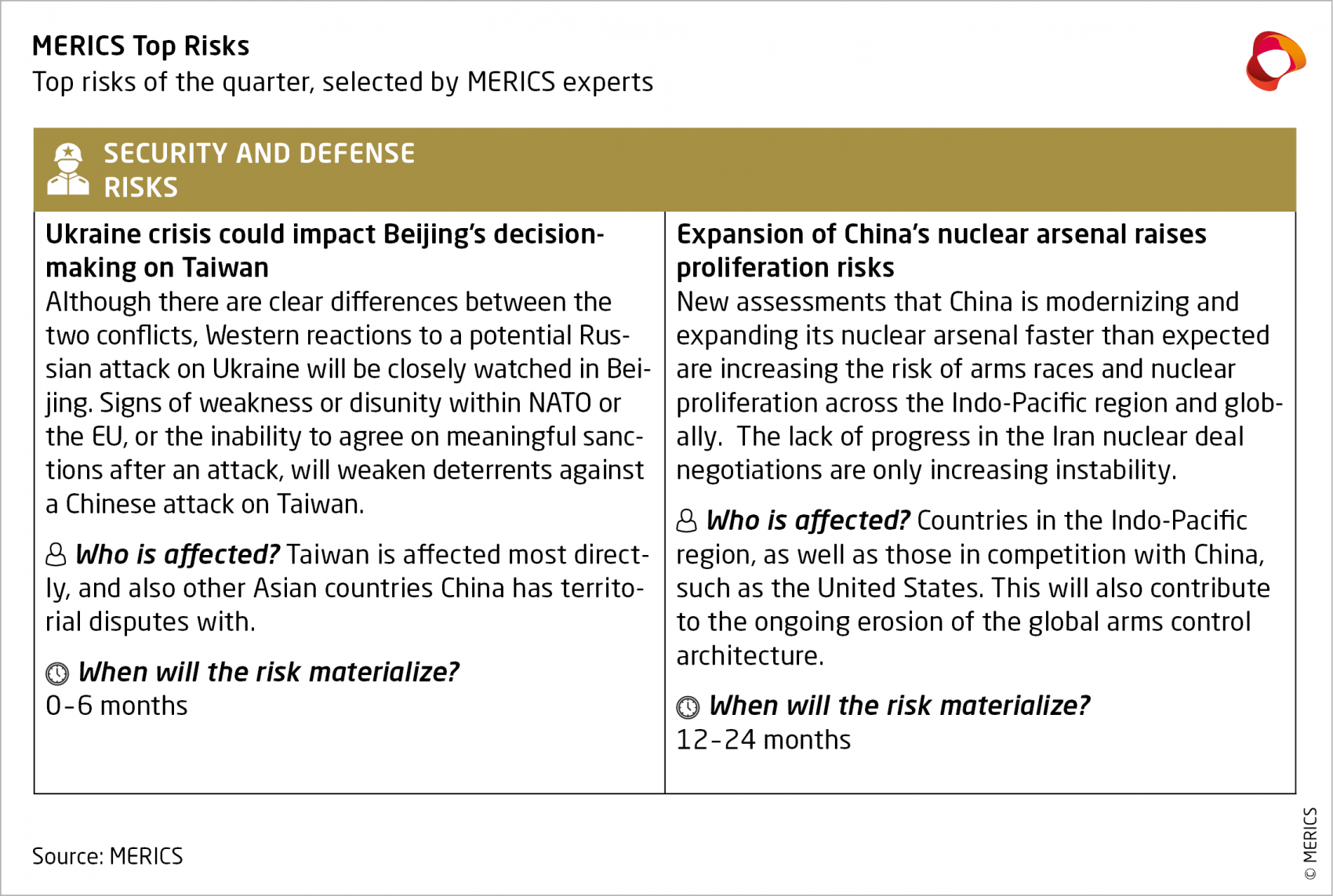

China is increasingly projecting power in its neighborhood, especially over the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea. The trend is set to continue unabated into 2022. Beijing now routinely makes large incursions into Taiwan’s air defense identification zone to “curb separatist acts by ‘Taiwan independence’ forces.”6 And some Chinese officials, such as Qin Gang, ambassador to Washington, are increasingly vocal on the risk of a US-China war over Taiwan.7 Support for Taiwan is increasing across the West. However, Taipei continues to lose diplomatic partners. Nicaragua switched recognition to Beijing in December, and the newly elected President of Honduras, Xiomara Castro, has also indicated the country wants to establish diplomatic relations with China.

In the South China Sea, China may be adopting a new argument to justify its claims over the entire area, after the “nine-dash line” concept was deemed illegal by a UN Court of Arbitration in 2016. Malaysian Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah noted in January that Beijing now favors the new concept of the “four sha” (or four sand archipelagos), which refers to the Pratas, Paracel and Spratly Island chains and Macclesfield Bank.8

In January, Beijing once more faced turmoil in its Western border as popular protests swept Kazakhstan. Following a request from Kazakh President Tokayev, Russia sent troops to the country to restore order, in a move that is sure to have caused some uneasiness in Beijing. In further evidence that the party will do everything in its power to prevent open conflict in its neighborhood ahead of the party congress, however, Chinese officials accepted – and even tacitly support –Russia’s involvement in the crisis. As long as stability was protected, Beijing seemed perfectly happy letting Moscow act as a security guarantor.

However, the risk of accidental escalation in China’s neighborhood remains high as foreign militaries step up their presence in the Indo-Pacific. The risk of confrontation is further increased by the accelerating regional arms race. The Pentagon’s annual report to the US Congress on China’s military power, released in November 2021, predicts that Beijing may have over 1,000 nuclear warheads by 2030 – four times the current estimate of around 250,9 although still significantly lower than the US stockpile of 3,750 nuclear weapons.

Heightened tensions did not stop a rare joint statement against nuclear war and nuclear weapons proliferation issued in January by the leaders of the UN Security Council’s five permanent members (all of them nuclear powers). However, the statement is unlikely to change the current dynamics of competition and rearmament between the US and China. US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin has called for the US to fast-track hypersonic missiles to catch up with China.10 Meanwhile, Beijing and Washington are racing each other to find and salvage an American F-35C fighter jet that crashed into the South China Sea. It carried highly classified technology that could be a boon for China’s military modernization process.

Geopolitical Competition

China, Russia deepen their relationship amid tensions with the West

Russia is keen on keeping China close as an ally against the West in any conflict over Ukraine, as can be seen in the unprecedented level of coordination between the pair over the past few weeks. On February 4, President Vladimir Putin met with President Xi on the sidelines of the Beijing Winter Olympics opening ceremony. It was the two leaders’ 38th meeting since 2013, and they used this opportunity to release an unprecedented joint statement re-emphasizing their partnership and outlining their ambitions for a reformed global order.11

The areas of cooperation outlined by the statement are not entirely new. But the explicit support for each other’s positions on controversial issues, alongside the balance between Chinese and Russian priorities in the document – and what this reveals with regards to the balance of power in the Sino-Russian relationship – make this a highly significant development.

Beijing joined Moscow in explicitly opposing NATO enlargement and it expressed support for Russia’s security concerns and interests in Europe. In turn, Moscow supported China’s stance on Taiwan and the pair opposed AUKUS and the formations of competing blocs in the Indo-Pacific. Despite this rhetoric, however, there are still limits to what each side will do for the other. The fact that the joint declaration seems to reflect Beijing’s language and priorities much more than Moscow’s is also a sign of the shifting balance of power in the relationship, which if increasingly tilting in China’s favor.

Great power competition in third regions is likely to escalate in 2022. Beijing has signaled its interest in maintaining its African presence with the publication of a new white paper on China-Africa relations12 and the appointment of its first-ever Special Envoy to the Horn of Africa.13 However, signals are mixed as the 8th Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), held in December 2021, showed a drop in the number of Chinese projects and investments compared to previous years.

The importance of China and of the China-Russia relationship in shaping Moscow’s decisions over the Ukraine crisis is becoming evident as the standoff continues.

In the West, concern has emerged over what China’s support for Russia might look like in a military conflict over Ukraine. Beijing will not send troops to Europe. Based on its response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, Beijing is instead likely to try to stay out of the fray once again. China is expected to straddle two goals – reluctance to damage its relationship with its closest partner and reluctance to legitimize or encourage military interventionism. Diplomatic support, however, is likely. Moscow has framed its position as a necessary response to Western hostilities, a narrative that Beijing has signed onto by criticizing the expansion of NATO and calling for Russia’s “legitimate security concerns” to be taken seriously. This was particularly evident in the Sino-Russian Joint Statement on International Relations in the New Era and Global Sustainable Development, released by Presidents Putin and Xi on February 4.

Overall, the crisis is bringing the pair closer together, with long-term implications for Europe and for NATO. A Russian attack on Ukraine would trigger the imposition of extensive sanctions by Europe and the US, which would leave Moscow economically dependent on China. This would, in turn, tip the scales even further in Beijing’s favor, allowing the Chinese side to increasingly dictate the terms of the relationship.

Beijing will also be watching the situation in Ukraine closely for its own purposes. Lessons drawn from the West’s response to a potential Russian attack will inform Beijing’s expectations surrounding any possibility of an attack on Taiwan. Although there are huge differences between the two conflicts, Beijing may use the Ukraine case to assess a) Washington’s appetite for fresh involvement in overseas conflicts, and b) the degree of unity and coherence within the West and NATO.

The repackaging of the BRI also sets the course for fierce competition around the globe with Europe and the US. President Xi promised the BRI’s future would be green and high-quality when he spoke to the third high-level symposium of the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing on November 19.14 The BRI is no longer exclusively about infrastructure. Standards are increasingly being promoted on all sides. Both the US rival to the BRI, ‘Build Back a Better World’ (B3W), and the European Union’s Global Gateway have chosen to emphasize sustainability and high-quality standards to distinguish their initiatives from the BRI.

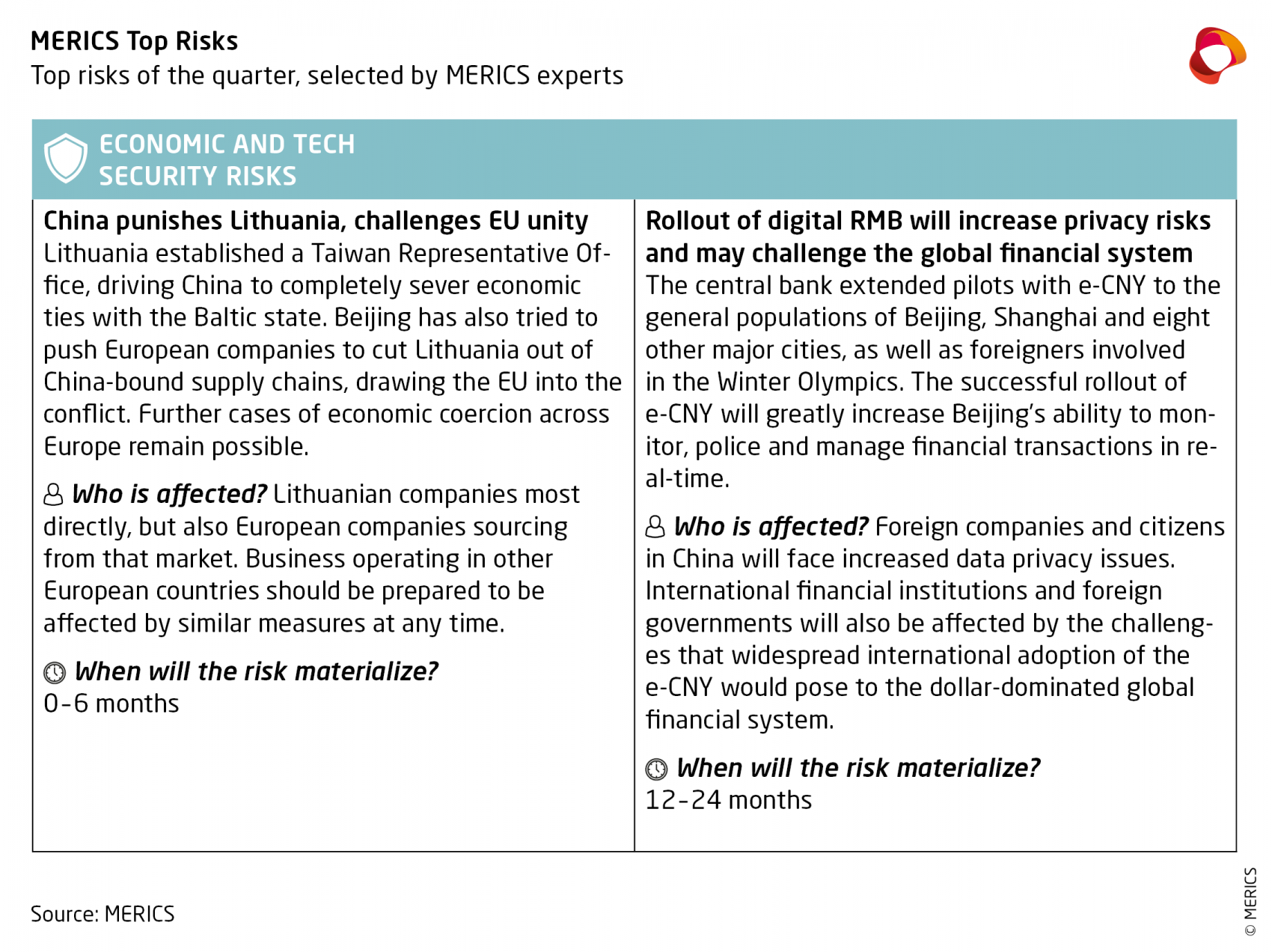

Europe-China relations, meanwhile, continue to suffer. Beijing’s economic retaliation against Lithuania is catalyzing debates across the EU on how the bloc can best protect its economic security. Brussels will simultaneously need to present a united front against China’s coercion, while considering how to avoid creating moral hazard. Its response needs to avoid incentivizing EU members to provoke political tensions that draw in the rest of the Union.

Meanwhile, the French presidency of the European Council looks set to advance the implementation of the EU’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, setting the stage for further tensions with Beijing.

Economic and Tech Security

Unclear signals from economic planning meeting risk policy-schizophrenia

In December 2021, Beijing held the Central Economic Work Conference (CEWC) to plan priorities for the following year.15 The meeting emphasized stability in economic policy in 2022. However, the readout listed seemingly every possible issue within its policy goals, in sharp contrast to the eight clear goals set out at the 2020 CEWC. The 2020 session set out an effective blueprint that was broadly followed by officials at all levels of government.

The lack of clear, tangible priorities from the CEWC will likely leave China’s officials unclear about what to prioritize with limited resources. If growth continues to slow, it is likely that Beijing will signal clearer priorities beyond merely “stability.” In the meantime, disjointed implementation across jurisdictions can be expected. Furthermore, officials may choose to prioritize a certain set of areas, only to find they must suddenly reverse course should official guidance from the top shift to other concerns.

Investors should anticipate potential sudden shifts in policy direction in the coming months and adopt a flexible stance in order to respond quickly.

Beijing sees data as the key to China’s digital economy

President Xi told the Politburo in October that developing the digital economy was needed more than ever. His speech, only recently published, emphasized China’s digital strategy amid a slowing economy, disrupted supply chains and growing foreign pushback.16 A series of policy documents followed in December and January that aim to mobilize China’s vast amounts of data, its “data dividend.” The digital economy is to create 10 percent of GDP by 2025, as stipulated in the 14th Five Year Plan for the Platform Economy, up from 7.8 percent in 2020. Keen to unlock the full potential of data as a factor of production, the 14th Five Year Plan for National Informatization comes close to framing data as a public good.17 To be sure, official plans also promote international data trade, with trusted partners and on Chinese terms.

Rather than nationalizing all data, China’s leadership wants the country’s private IT firms to help harness it. China’s homegrown Big Tech firms will continue to face mounting scrutiny and fresh regulatory pressures. The top anti-corruption watchdog, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, is investigating links between Big Tech and officials. The sector also faces scrutiny over investments and new regulations on recommendation and pricing algorithms. With limited evidence for how government can spur digital innovation, this is a high risk, high stakes experiment.

Looking forward: What to watch in the months ahead

- February 22: Paris hosts the first Indo-Pacific Forum, bringing together the foreign ministers of the EU-27 and 30 of their Indo-Pacific counterparts. China and the US have, rather conspicuously, been omitted from the guest list for an event meant to advance the EU’s Indo-Pacific ambitions.

- March 4-10: Beijing will host the annual Two Sessions meetings – a gathering of the National People's Congress (NPC) and the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC). The NPC will shed light on China’s policy direction in the run up to the 20th Party Congress and may endorse or propose future regulatory action in economic or foreign policy spheres. China’s budget for 2022 will also be announced.

- March: The EU will unveil the new Strategic Compass, which will lay out a common strategic vision and road map for security and defense work in the years to come. The challenges posed by China are bound to be considered in a document that will offer one of the first chances to revisit the 2019 Strategic Outlook’s view of China as a partner, competitor and rival.

- April 1: The next EU-China Summit will convene towards the beginning of the second quarter. Expect discussions to be overshadowed by China’s economic coercion against Lithuania and the EU’s response, including its filing of a World Trade Organization (WTO) case and the new anti-coercion instrument. The EU’s Indo-Pacific ambitions and China’s desire to revive the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) without removing its sanctions on European individuals and entities are also likely to prove contentious.

- Endnotes

-

1 https://merics.org/en/short-analysis/forecasts-2022-china-alone-home-and-decoupling

2 http://comment.cfisnet.com/2021/1230/1324702.html

3 https://m.thepaper.cn/rss_newsDetail_16287207

4 https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/wjbzhd/202112/t20211220_10471821.shtml ; https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/wjbzhd/202112/t20211230_10477287.shtml

5 https://chinamediaproject.org/the_ccp_dictionary/telling-chinas-story-well/

6 http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/view/2021-12/30/content_10119625.htm

7 https://www.npr.org/2022/01/28/1076246311/chinas-ambassador-to-the-u-s-warns-of-military-conflict-over-taiwan?t=1644601764809

8 https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/malaysia-southchinasea-01182022151031.html

9 https://media.defense.gov/2021/Nov/03/2002885874/-1/-1/0/2021-CMPR-FINAL.PDF

10 https://www.defensenews.com/industry/2022/02/04/top-pentagon-officials-met-with-industry-executives-about-hypersonics-what-comes-next/

11 http://en.kremlin.ru/supplement/5770

12 http://www.news.cn/english/2021-11/26/c_1310333813.htm

13 https://www.dw.com/en/horn-of-africa-china-announces-new-envoy-as-us-one-departs/a-60352823

14 http://www.china.org.cn/china/2021-11/20/content_77882970.htm

15 http://www.news.cn/politics/leaders/2021-12/10/c_1128152219.htm

16 http://www.qstheory.cn/dukan/qs/2022-01/15/c_1128261632.htm

17 http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-12/28/5664873/files/1760823a103e4d75ac681564fe481af4.pdf