Indonesia’s wary embrace of China

You are reading chapter 3 of the MERICS Paper on China "Beyond blocs: global views on China and US-China relations". Click here to go to the table of contents.

You are reading chapter 3 of the MERICS Paper on China "Beyond blocs: global views on China and US-China relations". Click here to go to the table of contents.

The two strongest factors shaping Indonesia’s relations with China today are domestic politics and the long-established Chinese diaspora, which is economically influential despite being only 3 percent of the population, Indonesia’s relations with China have swung sharply during the last 70 years, veering from close allies (1950s-1965) to enemies (1966-1990), to distant associates (1990-2014), to their current close partnership. Ethnic Chinese Indonesians have often played a part in promoting, or impeding, their country’s relations with China.

Status quo: Steady trade flows and limited security cooperation

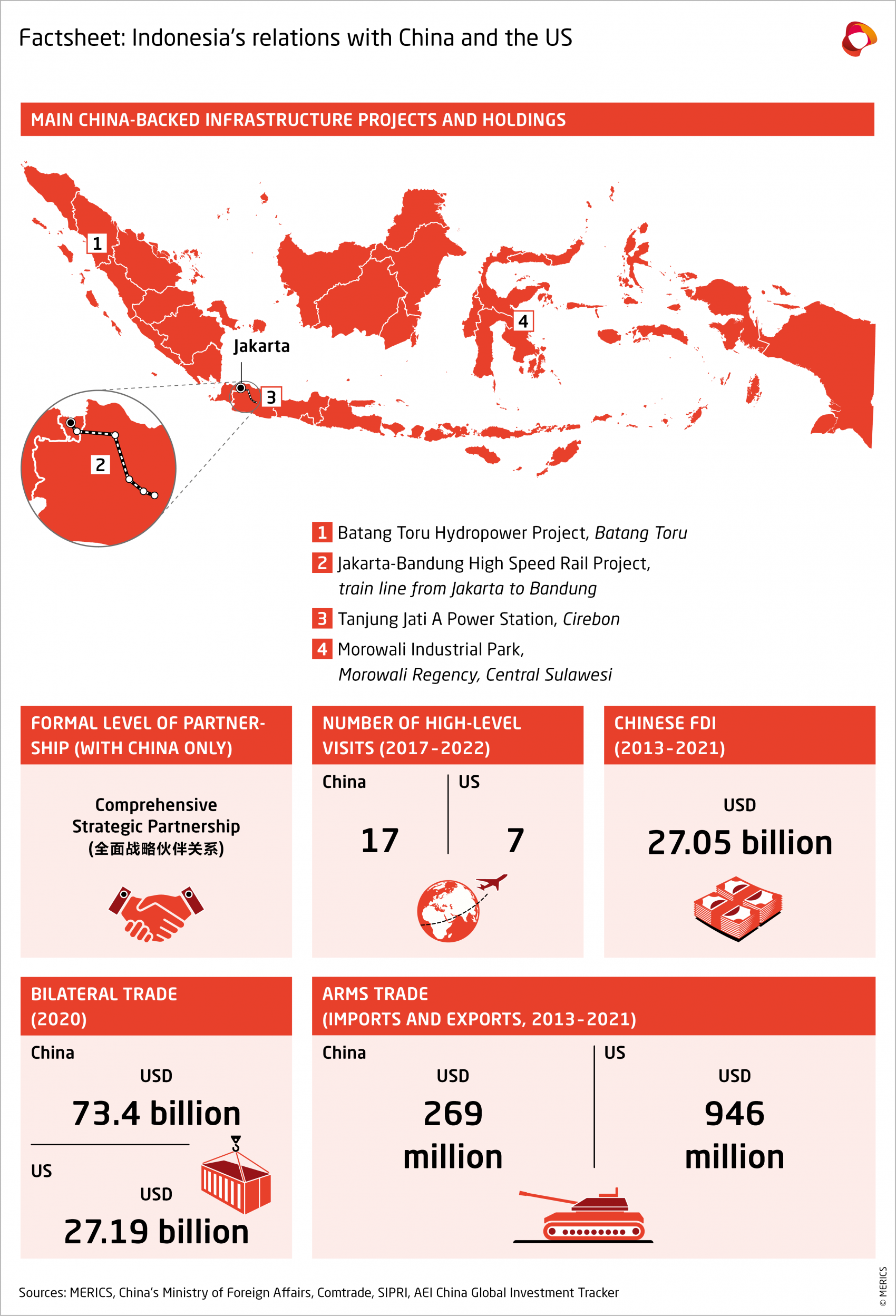

China has been Indonesia’s biggest trading partner since they signed the Indonesia-China Strategic Partnership in 2005. Trade flows increased steadily, turning in 2008 into a rising trade deficit for Indonesia. Indonesian exports are dominated by intermediate goods (37.33 percent) and raw materials (33.43 percent).1 Intermediate goods also form the largest share of Indonesian imports from China (31 percent), followed by consumer goods (18.79 percent).2

Two-way investment remained slight until it was boosted by President Joko Widodo and President Xi Jinping (who have a close personal relationship), leading to a surge in investment under China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Inbound investment from China, including Hong Kong, in 2019-2020, ranked second after Singapore.3 Chinese investment in Indonesia is concentrated in mining and the energy sector. As of 2021, Indonesia had the highest number of Chinese-built overseas coal-fired powerplants.

There are growing concerns among the Indonesian public about the influx of Chinese goods and migrant laborers, and about Indonesia’s inability to seize business opportunities in China’s market. The biggest Chinese investment project – the Jakarta-Bandung high speed railway – has become controversial due to project delays and cost overruns.

The role of ethnic Chinese Indonesians cannot be underplayed, as they are the main actors in economic relations between the two countries and, arguably, the ones who have benefited most from the relationship. Resentment of Chinese investment on perceived unequal terms also encompasses the Chinese diaspora and can generate domestic political frictions.

In the security sphere, the two countries have set up multiple confidence-building platforms, including the Annual Indonesia-China Defense Security Consultation Talk (established in 2006); the Xiangshan Forum; and the ASEAN Defense Ministerial Meeting Plus (ADMM Plus). Nonetheless, security cooperation remains extremely limited, despite the signing of the 2008 Joint Development of Defense Industry, Exchange and Training of Military Officers, and Joint Military Exercise in 2008 and the signing of a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership in 2013. The main reasons are the Indonesian military’s ongoing distrust of China, and public anxiety about China’s aggressive behavior in the South China Sea. Frequent incidents in Indonesia’s Natuna Sea (neighboring the South China Sea) have stoked fears about the threat China may pose to Indonesian territory. The risk of Uyghur terrorist operations in Indonesia is an additional security concern.

However, both China and Russia are seen as alternative security partners to counterbalance difficult relations with the United States and its Western allies.4 Western countries are generally perceived as hypocritical for their double standards on human rights. Frequent US-led interventions and subversion in developing countries are unpopular. Previous bitter experiences and distant relations with Western countries have driven Indonesia to seek other security partners.

Geopolitics: Growing US-China rivalry prompts new protection mechanisms

Indonesia has experienced bitter relations with both the US and China. Indonesia strives to operate an “independent and active” policy (bebas aktif) in response to US-China strategic competition, as is often the case amid big-power rivalry. For Indonesia, their rivalry presents opportunities as well as challenges.

Beijing has actively promoted investment and infrastructure projects through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), whereas Indonesia has seen no clear economic dimensions to Washington’s Indo-Pacific strategy. However, US allies such as Japan, the EU, and Australia have sought to enhance economic relations with Indonesia; these countries are perceived as alternatives to China, so Jakarta applies a hedging strategy. The United States seemingly prefers to support other regional countries such as Singapore and Vietnam when it comes to business opportunities and investment.

In 2021, China launched the Global Development Initiative (GDI) to promote cooperation in poverty reduction and the implementation of UN sustainable development goals (SDGs). The new global initiative expresses both Beijing’s growing global ambitions and its willingness to shoulder more ‘big power’ responsibilities by providing global public goods. The GDI’s eight focus areas are aligned with ASEAN’s Community Vision 2025 and Indonesian Development Programs. It can also be synergized with the Indonesian-sponsored ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP).

Indonesia’s government does not wish to take sides in geopolitical competition. Historical experience has shown the United States and China are equally capable of threatening Indonesia’s territorial integrity and security. Jakarta proposed the AOIP in a bid to pacify the Quad’s Indo-Pacific strategy to contain China: it seeks to turn points of tension into areas for cooperation and to include China, not exclude it. Indonesia has also expressed concerns about AUKUS, as it fears the anti-China alliance will provoke nuclear proliferation in the Pacific and threaten overall regional security, jeopardizing Indonesia too. However, though Jakarta avoids openly welcoming the US presence in the South China Sea, it needs US and allied support against Chinese a aggression. Indonesian diplomacy aims to build a stable region through dialogue and mutual trust; major extra-regional powers are welcome to cooperate, not to dominate, let alone to dictate.

Perceptions: A mix of respect, suspicion and caution

Indonesian perceptions of China and the Chinese are a major issue that significantly affects bilateral relations.5 Public discourse freely mixes up China as a country, PRC citizens and the ethnic Chinese descendants of earlier Chinese migrants to Indonesia; worsening identity politics has targeted both Indonesia’s Chinese minority and the PRC.

Indonesians admire China’s astonishing development and cultural richness, but they also fear China’s domination of the Indonesian economy and are concerned about Chinese assertiveness in the South China Sea. There is skepticism about the impact of China’s rise.6 Perceptions of Chinese economic dominance prevail at both public and elite levels. However, elite perceptions are divergent, ranging from the military and anti-communist groups who perceive China as threat, to moderate technocrats and bureaucrats who see both challenges and opportunities in China’s rise. Ethnic Chinese in the business community tend to be fond of China; many have sent the rising generation to work or study there in recent decades.7 Among elites and supporters of President Widodo, there is no clear steer as perceptions are divided between those who view China optimistically and those who are suspicious of Beijing.8

Some studies reveal Indonesian perceptions of China in particular issues. A study of the BRI found Indonesian diplomats had largely negative perceptions of Chinese intentions, but nonetheless welcomed the initiative and were optimistic it would benefit Indonesia somehow.9 Bilateral economic cooperation through the BRI has been limited by the influx of Chinese workers to projects in Indonesia, fear of China’s economic domination, its aggressive stance in the North Natuna Sea and the ethnic Chinese issue.10 Indonesians exhibited most positive sentiment towards China over the Covid-19 pandemic as it proved the most generous country in providing medical supplies, medicines, and vaccines.11

Positive perceptions may fade if China’s economic dominance and political influence grow, if it employs strong-arm tactics in the South China Sea, continues mistreating the Muslim Uyghur population in Xinjiang, or intervenes in domestic politics.12 Other possible triggers for negative feeling would be a major influx of mainland Chinese workers, any heightening of identity politics in Indonesia, or changes in China’s policy on Chinese overseas.13

Outlook: Indonesia's emphasis on the Global South offers China diplomatic opportunities

Overall, domestic audiences and international society both consider Indonesia’s government under President Widodo to be a close partner of China under President Xi. The personal factor seems to shape the relationship. However, public concern over China’s economic dominance, its naval assertiveness and mistreatment of Uyghurs have become sufficiently sensitive issues to hinder the government’s attempts to expand economic relations with China.

Indonesia’s regional and global stance is not to isolate China, a position that is consistent with its foreign policy principle of “bebas aktif” (independent and active). It is also rational and pragmatic, as the Asian giant has become the engine of global economic growth and offers more opportunities than other major powers. Through the GDI, China has also indicated more willingness and readiness to be a responsible major power that provides global public goods. Accepting China’s rise and working cooperatively to cope with the threats China poses seems more rational; condemnation and exclusion will fuel great power rivalries that, eventually, endanger Indonesian interests.

Nevertheless, it is imperative for Indonesia to continue putting (friendly) pressure on China as Indonesians do not wish to see a rising power emulate the unacceptable hegemonic behavior shown by the United States in the last several decades. US support for Israel and interventions in many countries, especially Muslim countries, for economic and strategic purposes have soured Indonesian public opinion towards it. Indonesian public wariness towards China is shaped by this rejection of hegemonic behavior. However, China’s criticism of frequently unfair and unilateral US conduct could help frame codes of conduct for an acceptable major power. On environment and climate change issues, China has shown itself willing to comply with international norms and to take the lead on some climate actions.

Indonesia needs to navigate carefully in its foreign policy to avoid being seen to lean towards any major power. The country also needs to enhance its national development in order to mitigate its dependence and become a more equitable partner. Working with Southeast Asian partners to enhance ASEAN’s centrality, and with other countries to strengthen global governance, is generally accepted among Indonesians as the route to a more participatory approach in creating a fairer new global order.

- Endnotes

-

1 | WITS. Trade Flow Indonesia-China 2019. https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/IDN/Year/2019/TradeFlow/EXPIMP/Partner/CHN/Product/all-groups. Accessed: April 16, 2022.

2 | Ibid.

3 | Indonesia Bureau of Statistics (2021). “Realisasi Investasi penanaman Modal; Luar negeri menurut Negara” (Realization of foreign investment by country). 2021. https://www.bps.go.id/indicator/13/1843/3/realisasi-investasi-penanaman-modal-luar-negeri-menurut-negara.html. Accessed: June 25, 2021.

4 | Fitriani, Evi (2021). ”Linking the impacts of perception, domestic politics, economic engagements, and the international environment on bilateral relations between Indonesia and China in the onset of the 21st century.” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies 10 (2): 183-202. Taylor & Francis

5 | Ibid.

6 | Herlijanto, Johannes (2019). “Public Perceptions of China in Indonesia: The Indonesia National Survey.” Perspective (89). Singapore: ISEAS.

7 | Fitriani, Evi (2018). “Indonesian Perceptions of the Rise of China: Dare You, Dare You Not.” The Pacific Review 31(3): 391–405. doi: 10.1080/09512748.2018.1428677.

8 | Herlijanto, Johannes (2017). “How the Indonesian Elite Regards Relations with China.” Perspective (8).

Singapore: ISEAS.9 | Yeremia, Adhitya (2020). “Guarded Optimism, Caution and Sophistication: Indonesian Diplomats’ Perceptions of the Belt and Road Initiative.” International Journal of China Study 11 (1): 21-49.

10 | Fitriani (2021). Loc.cit.

11 | Seah, Sharon et al. (2021). The State of Southeast Asia. Singapore: ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute

12 | Seah, Sharon et al. (2022). The State of Southeast Asia. Singapore: ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, 36.

13 | Suryadarma, Leo (2017). “The Growing ‘strategic partnership’ between Indonesia and China faces difficult challenges” Trends in Southeast Asia 5. Singapore: ISEAS.

You were reading chapter 3 of the MERICS Paper on China "Beyond blocs: global views on China and US-China relations". Click here to go to the table of contents.

You were reading chapter 3 of the MERICS Paper on China "Beyond blocs: global views on China and US-China relations". Click here to go to the table of contents.