Amended anti-espionage law aims to curate China’s own narrative

In July, a series of revisions to China‘s anti-espionage law are set to officially take effect. Vincent Brussee and Kai von Carnap argue the amendments’ essence is to give Beijing more control over the country’s global image.

Amid recent raids and arrests at foreign companies over alleged national security and espionage violations, China’s legislature recently passed a series of amendments to its anti-espionage law, set to take effect July 1. These moves could signal an impending crackdown on foreign journalists, researchers, and consultants – targeting almost anyone who exchanges information with international counterparts.

Compared to its 2014 predecessor, the amended law responds to a wider range of perceived threats to China’s national security and far expands the gray zone surrounding the government’s definition of espionage, as well as how violations are addressed. For instance, the new law adds “seeking to align with an espionage organization and its agents” as a violation (§4.2). Without a formal (public) definition, “espionage organization” could be taken to mean nearly any organization deemed unfriendly to China.

Moreover, its amendments define espionage not only as obtaining state secrets but also any other documents related to “national security” (§4.3) – a concept that has greatly expanded under President Xi Jinping. This means that virtually anything – from university research to multinational business dealings or even social media chats – could potentially fall under its purview and result in severe repercussions (criminal cases of espionage can be punishable by up to life imprisonment).

One example was recently documented by Chinese state media covering the arrest of a citizen engaged in supply chain audits. The company had cooperated with a foreign NGO to conduct a review of Xinjiang-related requirements and materials, where many companies have increased due diligence audits amid reports of forced labor in the region. As reported by state media, the company’s investigation jeopardized China’s national security by collaborating with the NGO that was “making a fuss” about human rights.

However, such principles have long existed in other laws and regulations. Hence, the amendments are not a turning point but rather another brick in the wall. It adds little new legal powers but makes clear recent developments are here to stay.

Codifying control

Although officially framed as countering espionage, the amended law’s actual intent seems to curtail how foreign observers can develop alternative perspectives on China. It puts into law what Xi Jinping already put into words in 2013, when he famously proclaimed he wanted to “tell China’s story well.” The idea is to make the Communist Party the sole narrator of China’s story, leaving its counterparts to listen passively. Xi no longer wants China to be studied by independent researchers or journalists who use their insights in ways that are outside of the party’s control. Instead, Xi wants observers to take the information straight from the horse’s mouth. Hence, information sources must be carefully selected and curated.

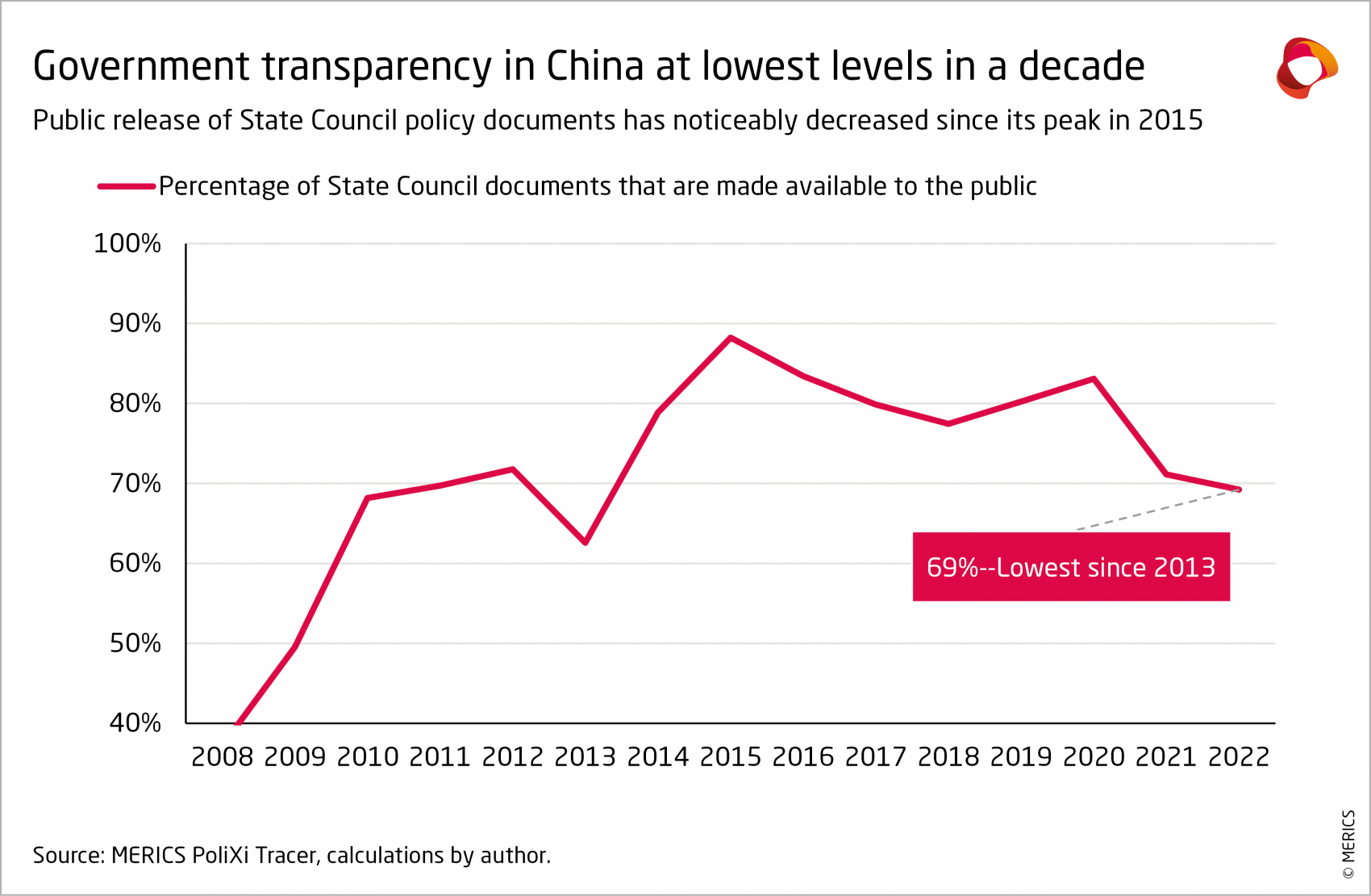

The anti-espionage law is one part of this dynamic – coercive capabilities targeting those that challenge China’s discourse power by acquiring sensitive information. The other side of the coin is that Beijing is sharing less information with the public. In 2022, the State Council, China’s top state organ, released approximately 21.5 percent fewer policy documents to the public (proportionally) than it did at its peak in 2015. New directives emphasize that government organs must carefully consider the goals and potential impact of information disclosure, while others have removed commitments to make disclosure the norm.

Non-governmental databases are shutting down access to foreign users, too. Popular company- databases Qichacha and Tianyancha suspended service to users without a Chinese phone number. Authorities required academic database CNKI to suspend several sources to international institutions. And the country’s leading financial database restricted international access in light of new rules on sensitive data.

Still, Beijing is unlikely to apply an extreme interpretation of what constitutes a threat to national security or shut off its internet from foreign access altogether, because doing so would damage China's reputation as a responsible superpower, a narrative it has been working hard to cultivate.

Another blow to trust

But the law's vast scope is likely to have a deterrent effect. Anyone who exchanges information with a foreign individual or entity will need to be extremely cautious and conduct an impossible assessment of whether they are potentially committing espionage. This will likely require compliance officers at companies to scrutinize multinational contracts with renewed vigilance, conference hosts to scrutinize their guest lists, and lecturers to review and possibly redraft their curricula.

These developments may also create a legal deadlock between jurisdictions. European governments are actively developing due diligence requirements for companies – for example, related to imports from Xinjiang. Yet authorities in China could consider the information-gathering for such a review as a form of espionage. As media coverage suggests, domestic Chinese citizens who are seen to cooperate with these measures could be at the greatest risk.

Although Chinese state media stress that the new law aims to keep anti-China forces from illegitimately collecting information to smear the country’s global image, the effects will go far beyond that. Some important sources for studying China outside official narratives will dry up, which will come at the cost of trust. Xi’s gambit appears that trust from the current US administration is long gone anyway, and that the country should focus on partners whose minds are still open to the party’s narratives. Whatever the calculus, China-related work will not be the same as it was several years ago.