China in 2021: agenda setting, anniversaries, and potential for conflict

Where does China stand at the end of 2020?

China has emerged from the Covid-19 crisis stronger and more assertive. While countries worldwide are sliding into recession, the People’s Republic has bounced back to moderate economic growth. In November, exports increased by a record-breaking 21 percent year-on-year. This shows that global demand for products ‘Made in China’ even increased during the crisis. On the political stage, life moving back towards normal after the Covid-19 crisis seems to have encouraged state and Communist Party leader Xi Jinping to once again become assertive. For instance, China recently declared it had reached its goal of overcoming "extreme poverty." Abroad, China is presenting itself as a cooperative partner in the fight against Covid-19 – although in the diplomatic arena it has started to show its teeth in countering criticism of its Hong Kong policy or in its dealings with Australia.

What is on the horizon for 2021?

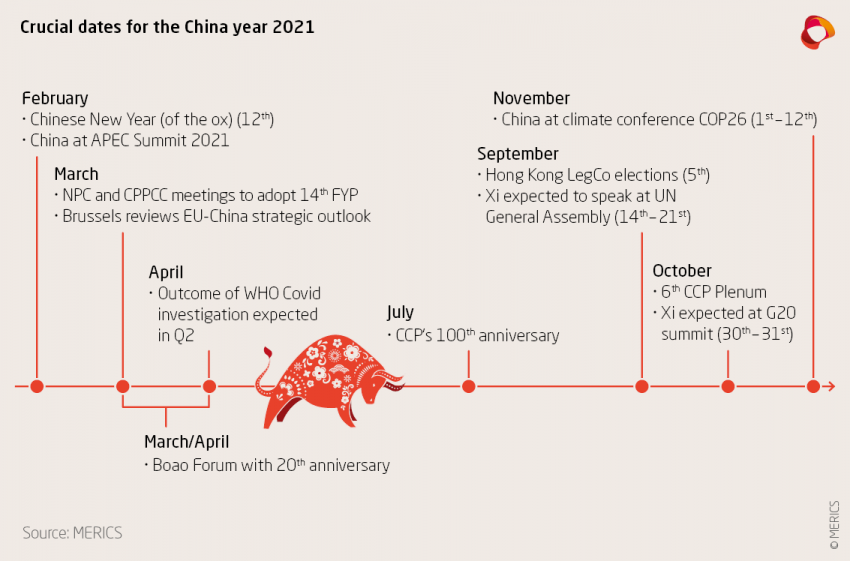

The Chinese leadership in 2021 will have important decisions to make – and big parties to throw: The 14th Five-Year Plan is due to be adopted in spring. It will set the agenda for achieving China’s ambition to become more economically independent and for taking the next steps to modernizing China’s industry. Innovation strategies – not least in fields like climate protection and environmental technology – will be at the forefront. At the same time, spending on "national security" and investments in digital surveillance systems are likely to rise significantly. In the runup to the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Xi will be keen on ensuring stability in the country.

The new data security law will bring changes for foreign companies active in China. In addition, the economy will continue to face big challenges, not only because of the sizeable debts of “too-big-to-fail" state-owned companies. The shaky global economy will also bear risks for China, which has granted billions of euros in loans to unstable economies as part of its ambitious Belt & Road Initiative. Beijing looks set for a major adjustment of its geopolitical and economic strategies.

Internationally, the APEC summit in February will show whether tensions with Australia will continue to escalate. Other countries also being targeted by China’s ‘Wolf Warrior Diplomacy’ - Sweden, but increasingly also Germany and other EU members - will have to keep a close eye on developments.

Focus: The China - USA - EU triangle and the global power play

EU-China relations were not easy in 2020. The fate of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment, which the German EU Presidency had hoped to finalize this year, is still undecided. In 2021, further tensions may arise: The EU is planning to revise its China strategy and the EU Council has just passed a new sanctions regime to respond to human rights violations that could also hit China. On climate cooperation, tensions between China and the EU could become apparent in the runup to the COP26 conference in November if the EU pushes ahead with its plans for a CO2 border tax.

Another decisive factor in EU-Chinese relations will be whether the transatlantic alliance can be revived after Joe Biden becomes US President. The US and the EU would send a powerful signal if they join forces in the face of China, for example over economic, security or human rights issues.

One thing is certain, China will continue to gain influence globally. Its “vaccine diplomacy” will probably contribute to this: China supplying urgently needed Covid-19 vaccines – as it is currently doing in Indonesia – will shore up relations with developing countries. The results of a WHO study into the origins of the pandemic, currently underway in China, will be unlikely to affect this development.

MERICS Executive Director Mikko Huotari says: “In 2021, you should expect a more radical China: more radically focused on innovation and economic self-reliance, more radical internally in its political hardening, and more radical in expecting alignment or acquiescence by its global counterparts. In US-China relations, we might see a tactical softening of relations. Thinking in Beijing will, however, be even more shaped by friend-foe distinctions, striving for comprehensive national strength, geo-economic spheres of influence and control or dominance in strategic value chains.”

Media Coverage and sources:

- Taipei Times: Extreme poverty over, Xi says

- FT: China curtails overseas lending in face of geopolitical backlash

- Forbes: Behind recent good news, China’s economic prospects look dubious

- FT: Zhao Lijian - the provocateur driving China’s ‘wolf warrior’ pack

- EU Council: EU adopts a global human rights sanctions regime

- SCMP: EU and Britain – for now – decline sanctioning Chinese officials

- China Dialogue: Policy Brief on EU-China climate engagement

- Foreign Policy: What is Europe’s “once in a generation offer” to America?

China says poverty is over and the next Five-Year Plan ready

Where do we stand? Xi Jinping in 2020 announced the dawn of a new era of “moderate prosperity” after China declared victory over absolute poverty, a political milestone that took decades to reach and required billions in spending. Success involved lifting the whole population over China’s self-defined poverty threshold of about USD 350 (EUR 290) a year, an income level somewhat lower than the current international standard of about USD 693. Many struggling households this year rose above the poverty line thanks to government cash payments and relocations. But without jobs and economic growth in poorer areas, it will be difficult for many Chinese to keep their annual income stable. With slowing growth, an ongoing pandemic, and a growth model driven largely by supply-side measures and in dire need of restructuring, poverty will remain a challenge.

Where are we heading in 2021? Beijing’s strategy to address these issues will be presented in the 14th Five-Year Plan. Details are due in March, but a draft proposal published in October suggests a doubling down on party- and state-led development. The plan is framed as a first step into a new period – one in which China will see “profound adjustments in the international balance of power,” but also the “strategic opportunity” to establish itself as global leader. Keenly aware of socioeconomic hurdles such as poverty, the plan pledges to create “quality growth” by modernizing industries, achieving industry leadership in more value-added markets, and switching to a more demand-driven growth model. However, the Five-Year Plan’s very statist nature will continue to favor political guidance and priorities over market mechanisms. This means that industrial policy and state-support for specific industries and sectors will continue.

MERICS analyst Nis Grünberg: “China’s main challenge remains a social one. 600 million Chinese citizens still live on a monthly income of around USD 140. Beijing needs to lift hundreds of millions from precarious low incomes to more sustainable middle-income levels. With inequality rising to painful levels, the coming years will require redistribution from the rich coastal areas to inland areas to provide income for those recently lifted out of – and those barely staying above – the worst poverty.”

More on the topic: Video recording of a MERICS web seminar on the coming Five-Year Plan and what we can expect

Media coverage and sources:

- CSIS: China’s Fifth Plenum

- China Daily: China’s victory over poverty

- SCMP: Xi declares victory over poverty

- Global Times: 600 million with 140 USD monthly income worries top leadership

METRIX

This is the number of Chinese citizens who live below China's absolute-poverty line, which stands at an income of 2,300 yuan per year at 2010 prices, roughly USD 350 (EUR 290). China in November said it had eliminated absolute poverty, a month before the deadline it had set itself. In 2012, authorities still counted about 100 million very poor citizens.

This is the number of Chinese citizens who live below China's absolute-poverty line, which stands at an income of 2,300 yuan per year at 2010 prices, roughly USD 350 (EUR 290). China in November said it had eliminated absolute poverty, a month before the deadline it had set itself. In 2012, authorities still counted about 100 million very poor citizens.

EU eager to work with the US on tech to face China despite divisions

Where do we stand? With China in mind, the EU wants to work closely with the incoming Biden administration on technology and digital governance, amongst other issues. In their proposal for a transatlantic agenda announced on December 2, the European Commission and the High Representative call for a new EU-US Trade and Technology Council to develop joint standards and regulations for advanced technologies, protect critical technologies, promote joint research and innovation, and ensure supply chain security. Based on “shared values of human dignity, individual rights and democratic principles,” the EU also wants to deepen cooperation on artificial intelligence, 5G and 6G security, data flows, and online platform regulation.

Where are we heading? It remains to be seen whether the two sides can overcome their divergences to “face the challenges of rival systems of digital governance,” an expression in the EU’s pitch which clearly refers to Beijing. Divisions and mistrust run deep, with transatlantic data transfers now in limbo following the Schrems II ruling and upcoming legislative proposals from Brussels potentially tightening competition and content scrutiny of American digital platforms. Much will depend on what stance Joe Biden takes on Big Tech, but there is also common ground to build upon. For example, both sides are concerned about China’s state-coordinated transfers of foreign technology, an area in which Trump took unilateral actions that alienated many in Europe. Biden is likely to remain tough on Chinese tech, but he will do so by engaging allies rather than pushing an “America first” rhetoric or full decoupling.

MERICS’ analyst Rebecca Arcesati: Beyond the defensive agenda of tech protection, Biden’s commitment to reinvigorating democracy and investing in innovation provides fresh opportunities for much-needed transatlantic coordination on norms and standards for emerging technologies, an area in which China is very proactive. There is even room to extend the Commission’s proposed agenda further – for example, by joining efforts on digital connectivity and supporting innovators in the Global South to provide alternatives to China’s Digital Silk Road.

Media coverage and sources:

- European Commission: Joint Communication: A new EU-US agenda for global change

- POLITICO: EU-US “tech alliance” faces major obstacles on tax, digital rules

- POLITICO: Step one in repairing U.S.-EU relations: a data privacy deal

- Financial Times: EU vs Big Tech: Brussels’ bid to weaken the digital gatekeepers

- Foreign Affairs: Joe Biden’s Foreign Affairs essay, published in spring but useful to gauge his thinking on China

- Reuters: Biden adviser says unrealistic to 'fully decouple' from China

- Reuters: Top Biden advisor seen as making tech regulation more likely

China will be the only large economy with a positive growth

Where do we stand? China has largely fared better than the rest of the world in handling the coronavirus pandemic, escaping recession by instituting short but relatively harsh lockdowns and state-driven recovery. China will be only large economy with a positive growth this year and is expected to grow around 2 percent. Stock markets are performing well, unemployment is low at 5.3 percent, and it in November recorded its largest monthly trade surplus ever, some USD 75.4 bn.

Where are we heading in 2021? Economically, China will likely fare well this year, with gross domestic product growing (GDP), mostly thanks to investments and exports. Despite Beijing’s large-scale economic stimulus booting domestic demand remains a challenge. Loose monetary policy and fiscal support will likely have to continue well into 2021 as domestic demand recovers only slowly,

MERICS analysis: The situation is difficult because Beijing cannot continue stimulus indefinitely with a financial system as shaky as China’s. Most indicators of financial stability have deteriorated the past year. Total credit to GDP ratio is up some 35 percentage points, shadow banking is recovering, and profits are a lot lower than last year. At the same time, interest rates have increased, and several major companies have experienced financial difficulties But the government will be cautious in rolling back its support as long as demand does not fully recover. The government seems to be implementing mostly supply-side ideas such as industrial upgrading and organization to combat the demand problem. Demand side policy – i.e., raising purchasing power – will be needed to guard against a future large-scale overcapacity problem.

Media coverage and sources:

REVIEW: China’s Quest for Foreign Technology by William C. Hannas and Didi Kirsten Tatlow

The Chinese state has operated and steadily expanded a sophisticated system to acquire foreign technology through a combination of legal, illicit, and extra-legal channels. Even though it’s no longer a developing country, China seems to have no intention to abandon this playbook. Western countries’ complacency about this rests on some dangerous assumptions and misconceptions. First, that China's historic bias towards applied innovation and against basic scientific research – dismissively called its “copycat culture” – would prevent it from catching up with more advanced nations. Second, that Chinese researchers, after studying in the West, would bring democracy back to their country. Third, that China shared the same values of open markets, fairness, transparency and reciprocity in business and research. Each of these assumptions has proven to be wrong.

With contributions by leading experts, China's Quest for Foreign Technology lays bare Beijing's state-coordinated efforts to spot, transfer and absorb foreign technology and talent to serve national economic, strategic and military goals while reducing the costs of indigenous innovation. From the role of Chinese professional associations overseas and of the United Front apparatus in China's technology transfer networks to startup competitions and partnerships involving institutions linked to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and foreign multinationals and universities, the contributors offer vivid and meticulous accounts of the system. They describe its vectors, enablers, workings, successes – and its impact on innovation ecosystems in democracies from Europe to South Korea. The book is packed with original insights, case studies, profiles and analyses of key Chinese-language texts.

The book’s many recommendations are very valuable for readers in Europe, where the phenomenon remains strikingly under-researched despite the region being one of the main targets of Chinese acquisition efforts. European engagement with China on scientific research and technology for too long has failed to factor in much needed risk awareness and mitigation measures. The book challenges “simple notions of 'win-win' techno-globalism,” including through an account of the role of Europe-based Chinese professional associations in tech transfers and their close relationship with the Chinese Communist Party's political influencing structures.

Reviewed by Rebecca Arcesati

PROFILE

In October, 35-year-old artist Deng Yufeng and a group of volunteers tried to walk down a road in Beijing without being detected by the 90 surveillance cameras in the area. The journey of 1,100 meters took over two hours as the artist and his helpers were seen twisting their bodies, shuffling sideways and sliding their backs along walls to avoid the gaze of prying lenses. All this was part of the performance art project “A Disappearing Movement,” devised by the Beijing-based artist to raise awareness about collective surveillance and the pressures of technology on individual privacy.

Born in Hubei and a 2010 graduate of the province’s Academy of Fine Arts, Deng is no stranger to controversy. For a solo exhibition in 2018, the artist lined the walls of a local museum in Wuhan with over 300,000 sets of personal information purchased online. He had wanted to display the extent of data breaches in China, but police shut down the show after only two days and accused Deng of illegally amassing private data. Deng later said he had paid just US$800 on the black market for the data, which included people’s names, gender, phone numbers and online shopping records.

Deng’s work is timely. It is estimated that China will have 560 million cameras installed by 2021, many of them with facial recognition capabilities. The Covid-19 pandemic has also seen China step up the use of facial scanners in the name of protecting public health. There is public pushback, but most of it is directed at commercial misuse. Last month, in a landmark case, a court in Hangzhou ruled in favor of a law professor who sued a zoo for collecting his facial data. But Deng’s latest project has received no coverage in China – very possibly because it’s too provocative for the country’s state media.

Profiled by Valarie Tan, Analyst at MERICS

Media coverage and sources:

- BBC: How to 'disappear' on Happiness Avenue in Beijing

- New York Times: The Personal Data of 346,000 People, Hung on a Museum Wall

- South China Morning Post: This man hides from security cameras in Beijing: it’s not crime, it’s art

MERICS China Digest

MERICS’ top 3:

- International Crisis Group: Two years on, China still holds Michael Kovrig in arbitrary detention

- CNN: China to expand weather modification program to cover area larger than India

- Sixth tone: In cashless China, criminals are punished with payment app bans

International relations:

- New York Times: US tightens Visa rules for Chinese Communist Party members

- Quartz: Uganda uses Huawei's facial recognition tech to crack down on dissent

- SCMP: EU and Britain decline, for now, to sanction Chinese officials involved in Hong Kong and Xinjiang actions

Economy, finance and technology:

- CGTN: Why China's CPI growth rate is at its lowest level since 2009

- FT: Huawei invests in China chip groups as US curbs strangle supplies

- SCMP: China claims quantum computing leap

- SCMP: Chang’e moon mission is ready to return to Earth

Politics and society: