Saudi Arabia’s once marginal relationship with China has grown into a comprehensive strategic partnership

You are reading chapter 7 of the MERICS Paper on China "Beyond blocs: global views on China and US-China relations". Click here to go to the table of contents.

You are reading chapter 7 of the MERICS Paper on China "Beyond blocs: global views on China and US-China relations". Click here to go to the table of contents.

Saudi Arabia is unlikely now, or in the immediate future, to turn to China as a military replacement for the United States as good relations with Washington remain a key Saudi foreign policy objective. However, Riyadh may begin to seek multiple political-security arrangements over time, should the developing rift with Washington deepen, or the United States pay less attention to the Middle East.

Status quo: Cooperation is expanding across many policy issues

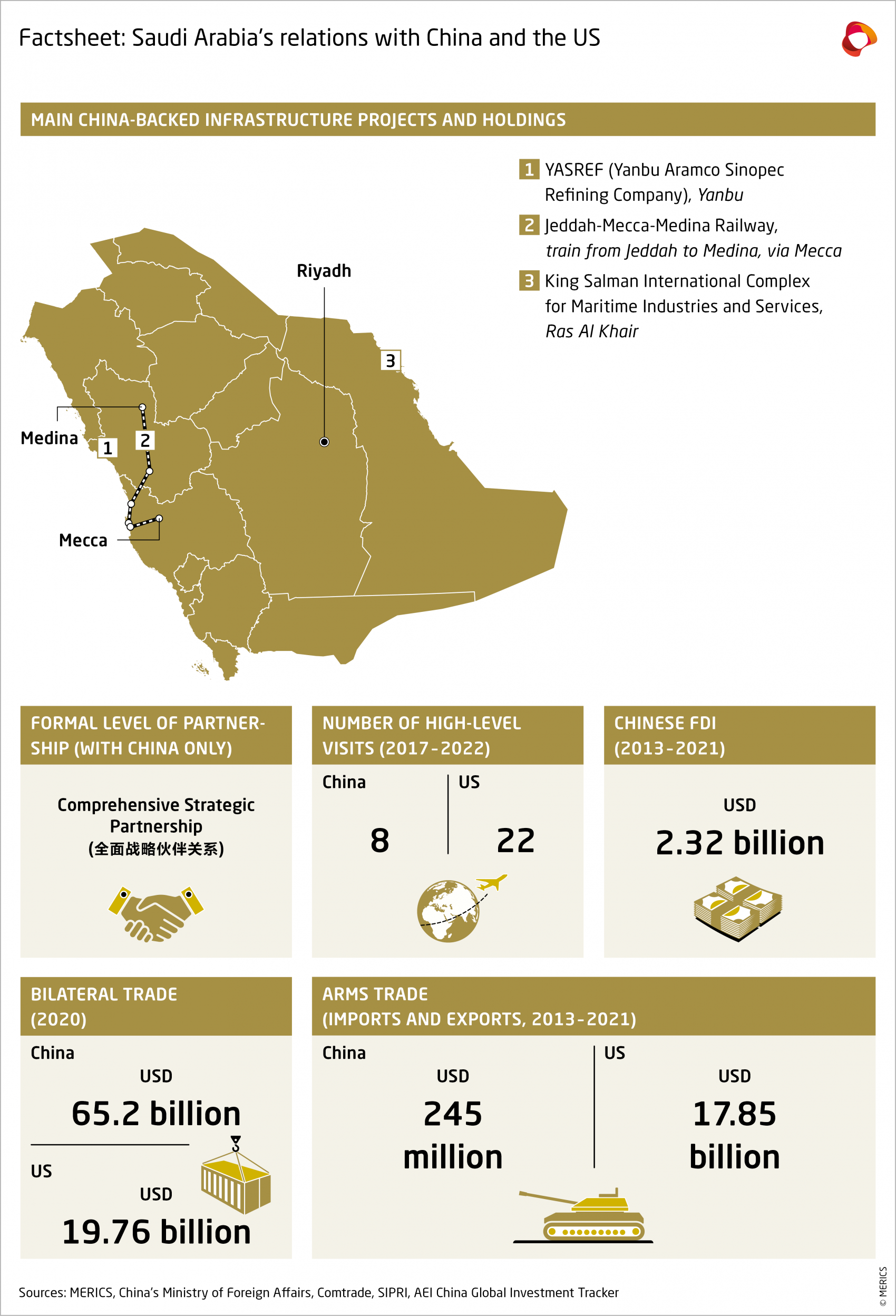

Over the last thirty years, Sino-Saudi political, economic and military ties have deepened. Saudi Arabia has become China’s largest trading partner in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), and China’s top global supplier of crude oil.1 Conversely, China is Saudi Arabia’s biggest trading partner and crude oil customer.

Last year, China took 27 percent of Saudi Arabia’s total crude oil exports, lifting its volumes by 3.4 percent to an annual record of 1.75 million barrel per day (mb/d). This happened even as China’s overall crude imports fell for the first time in 20 years.2 China is also the largest trading partner for Saudi Arabia’s chemical industry, taking almost a quarter of the Kingdom’s exports from this sector.3

Their bilateral trade involves huge sums but remains narrowly based; more than 95 percent of China’s 2021 imports from the Kingdom consisted of petroleum oils, plastics, and organic chemicals.4

Annual bilateral trade volume was worth USD 87.31 billion at the end of 2021, an almost 209-fold increase from USD 418 million when diplomatic relations were established in 1990, just over thirty years ago.5

Saudi Arabia has also been the largest regional recipient of Chinese contracting and investment, which totaled nearly USD 43.5 billion between 2005 and 2021.6 In turn, Saudi Arabia has invested or is planning to invest about USD 35 billion in China-based projects, with production capacity reaching 7.5 million tons of chemicals, amounting to 45 percent of total overseas production capacity for Saudi producers.7

The scope of Sino-Saudi cooperation has expanded in recent years, branching out from the energy trade into investments in infrastructure, communications, high-tech, industry, finance, transport, renewable and nuclear energy, and arms production.

Co-operation has been bolstered by bilateral and regional coordination mechanisms to create synchronicity between China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Kingdom’s Saudi Vision 2030. The latter is a Saudi development strategy that aims to reduce Saudi Arabia’s reliance on oil, promote economic diversification, shrink the public sector’s footprint and promote private sector development. These two mechanisms have fostered significant cooperation in many economic and investment areas.

Political ties have also developed steadily as the relationship between Riyadh and Beijing has grown from one of marginal importance into a “comprehensive strategic partnership.”8 Both sides have focused attention on common ground and avoided causes of conflict such as human rights, or any comment on each other’s domestic affairs. This framework of delicate diplomatic interaction has so far proven a success.9

However, China’s improving relations with Iran may cause discomfort among Saudi leaders. Beijing and Tehran recently signed the 25-year China-Iran Cooperation Programme which reportedly enables China to buy energy cheaply in exchange for a commitment to significant investments in Iran’s economy. For Riyadh, military cooperation between China and Iran is a major concern. So far, Beijing has taken a cautious approach toward Tehran, despite supporting the Iran nuclear deal. However, it is a certainty that the Saudis will monitor China-Iran relations – especially in the event of sanctions on Iran being lifted – and will be alert to any impacts on Saudi national security.

Sino-Saudi defense ties remain limited in scope, despite greater bilateral economic and diplomatic engagement. Defense ties are confined to joint exercises, counter-terrorism cooperation, sales of some weapon systems, and joint production of armed unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs).10 Beijing has limited capacity to compete with Western arms suppliers, while the Saudi military’s long-term dependence on US hardware means that Chinese arms will not easily integrate with pre-existing systems. In general, it takes years to complete diversification of weapons sources or any move towards local manufacture.

However, China has reportedly helped Riyadh to set up a nuclear program, including a “secret” yellowcake extraction plant, and improve its solid-fuel ballistic launcher capabilities.11 Although Riyadh “categorically denies” that it has built a uranium ore facility in the area described by a media report, Saudi Arabia’s energy ministry Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman confirmed the existence of a contract with China for uranium exploration in certain areas.12 Prince Abdulaziz also confirmed that his country has plans to develop its uranium resources with a view to supporting its nascent nuclear power program. “We do have a huge amount of uranium resource which we would like to exploit, and we will be doing it in the most transparent way (..) We will be bringing partners and we will be exploiting that resource, and we will be developing all the way to the yellowcake,” Saudi Arabia’s energy ministry told the Future Minerals Summit in Riyadh in January 2022.13

There is also potential for Chinese companies to win more Saudi defense procurement deals over the next decade, particularly as Riyadh may seek to strengthen strategic ties with Beijing and receive technology transfers through offsets, particularly for drones, light weapons, and some types of armor or even missiles.14 Saudi Arabia was the world’s second- largest arms importer in 2017-21 (just behind India) and accounted for 11 percent of all imports of major arms. Nevertheless, Saudi Arabia purchased less than 1 percent of its arms imports from China in that period. The United States was by far the largest arms supplier to Saudi Arabia in 2017-21, supplying 82 percent of the Kingdom’s arms imports.15

Saudi Arabia’s strong US military ties may limit Riyadh’s openness to any increased Chinese military presence in the Kingdom – at least in the short term. Riyadh’s ability to maneuver US-China tensions is likely to be tested in the months ahead as Washington may well pressure Gulf Cooperation Council states to limit their interactions with China, especially if Beijing faces secondary US sanctions linked to the war in Ukraine.

Geopolitics: Seeking a balance between Washington and Beijing

Although Saudi Arabia seeks economic and diplomatic benefits from a greater Chinese role in the Middle East, Riyadh knows it must balance such long-term benefits against the more immediate imperative not to alienate the United States.16 Saudi Arabia is also aware that China’s sustained economic growth may eventually translate into increased military power, expressed in more assertive strategies in the Middle East and beyond.

However, Saudi leaders do not believe China possesses the necessary capabilities to provide a credible alternative to the US security umbrella in the Gulf or broader Middle East.17 Nor is China strategically motivated to do so. Riyadh faces complications from any US pressure to limit engagement with China, particularly in military affairs. It needs to find a difficult balance between deepening ties with China, its top economic partner, and appeasing its historic ally, the United States.18

To this end, Saudi Arabia is working along parallel routes: strengthening its independent military capabilities and aggressively diversifying economic and military ties with key external players. To offset declining US security support in the near term, Saudi Arabia will increasingly look to strengthen defense ties with European countries, plus China, India, Brazil, South Africa and even Turkey. It will hope these other partners can pump substantial investment into the growing Saudi arms industry. Eventually, the kingdom may also be tempted to deepen its defense ties with China and expand the ballistic missile program it is developing with Beijing’s help.

Perceptions: Growing sympathy with China's political model

Saudi political and business elites increasingly perceive China as a superpower in the making and expect it to remain a top destination for their energy exports for the foreseeable future, making it vital to cultivate strategic relations with the rising power.

- Diplomacy: China is a permanent member of the UN Security Council (UNSC), and its political influence will increase over time as its economic and military power grows. Saudi leaders express appreciation for China’s growth model, non-intervention policy, and opposition to interference in Saudi Arabia’s internal affairs. The country has supported China’s positions on Xinjiang and Hong Kong.19

- Economics: China is the world’s second largest economy and could surpass the United States by the end of the 2030s. Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) has applied for a license that would enable it to make major investments in Chinese companies. This is a new direction for PIF as it has so far focused on US and European overseas holdings. As a Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (QFII) license-holder, PIF will be able to trade renminbi-denominated stocks directly, instead of through third parties.20 In the energy sector, China is the world’s largest energy consumer and top largest oil importer. According to projections by the International Energy Agency (IEA), China will remain Saudi Arabia’s top crude market for the foreseeable future.21 Although Saudi leaders have pledged to diversify, to develop new sources of non-oil income, the Saudi economy will depend on energy exports for many years to come.22 New opportunities are emerging from the Saudi Green Initiative program, which promises to facilitate some USD 190 billion-worth of green investment by 2030.23 As China is the world’s leading manufacturer, user, and exporter of green technologies, Saudi projects can bolster China’s domination of the green energy supply chain.24

- Military: China has the world’s largest army; it is a nuclear power and has the second- largest military budget after the United States. Many Chinese weapons remain less technologically sophisticated than those of Western military powers. However, China is expected to close the technological gap during the next decade or so.25

Beijing’s efforts to advance the BRI in the Gulf seem to be broadly welcomed by the Saudi population, though the lack of independent polling makes it challenging to gauge Saudi public opinion. There are no well-established local polling firms and government influence has an inhibiting effect on the sector and the public. A recent poll commissioned by the Washington Institute on key foreign policy issues found that almost 50 percent of Saudis view good ties with China as “important,” compared with 37 percent who regard the United States as important.26 A recent Ipsos survey on the future of the world order reported that 84 percent of Saudi respondents agree China offers a political and economic model for their country to emulate.27

Here, it is worth noting that the catastrophic repercussions of the so-called Arab Spring of 2011 have undermined the attractiveness of the Western model of democracy. China’s political model, at least as perceived in Saudi Arabia by respondents ranging from the political elite to ordinary citizens, gets points for avoiding political tumult and for its association with stability and economic growth.

Outlook: Riyadh distances itself from seemingly unreliable Washington

Washington’s growing reluctance to engage militarily in the Middle East has stoked concerns among Saudi leaders that the United States cannot be counted on for support in the event of a conflict. The rapid US withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 provided the starkest example yet of its desire to disentangle itself from lengthy, costly Middle East conflicts.28

It appears that Saudi Arabia is already preparing for the eventuality that the United States may be reluctant to intervene in crises. The Saudi-led intervention in Yemen’s civil war since early 2015 reflects this. Riyadh has been acting more independently of the United States in recent years, setting a new norm that is likely to persist.29

From the Saudi perspective, Iran is the primary security challenge in the Middle East regardless of whether the United States rejoins the Iran nuclear deal or not. US policies and a renewed Iran nuclear deal are likely to ease regional tensions, but Riyadh fears the consequences. Once pressure on Iran eases, Tehran will be freer to resume an assertive foreign policy over the medium-to-long term and threaten Saudi interests.30

Some of these Saudi concerns appear to resonate in Beijing. US intelligence agencies reportedly believe Saudi Arabia is now actively manufacturing its own ballistic missiles with China’s help.31 More broadly, if the Saudi elite lose faith in US willingness to defend their interests, perhaps due to the failure to halt Iran’s nuclear program, the Kingdom will be more likely to accelerate its own nuclear programs.32

- Endnotes

-

1 | Saudi Arabia has remained China’s top supplier since 2002, losing that place to Russia only briefly in 2016-2018.

2 | See: MEES (2022). “China 2021 Crude Imports: Saudi Top As Iran Volumes Rise.” January 21. http://archives.mees.com/issues/1938/articles/60490. Accessed: January 29, 2022. And MEES (2022). “Saudi Crude Oil Exports Sink To 11-Year Low For 2021; Now For The Rebound.” January 7. http://archives.mees.com/issues/1936/articles/60427. Accessed: January 29, 2022.

3 | Al-Tamimi, Naser (2022). “China and Saudi Arabia From enmity to strategic hedging.” In: Fulton, Jonathan (eds.) Routledge Handbook on China-Middle East Relations, 137-154. London and New York: Routledge. P. 143

4 | See: https://comtrade.un.org/

5 | General Administration of Customs of the People's Republic of China (2022). “Total imports and exports by country or region 2021.” http://www.customs.gov.cn/customs/302249/zfxxgk/2799825/302274/302277/302276/4127455/index.html. January 18. Accessed: February 11,2022.

6 | See China Global Investment Tracker. https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/

7 | Chen, Dongmei. KAPSARC (2021). “China’s BRI and Saudi Vision 2030: A Review to Partnership for Sustainability.” https://www.kapsarc.org/research/publications/chinas-bri-and-saudi-vision-2030-a-review-to-partnership-for-sustainability/October 24. Accessed: February 6, 2022.

8 | Ibid.

9 | Al-Tamimi, “China and Saudi Arabia: From enmity to strategic hedging.” Ibid, p. 142.

10 | Ibid, p. 146.

11 | Lim, Kevjn. Institute for National Security Studies (2021). “China-Iran Relations: Strategic, Economic, and Diplomatic Aspects in Comparative Perspective.” https://www.inss.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Memo213_e.pdf. Accessed: February 1, 2022.

12 | Middle East Eye (2020). “Saudi Arabia constructs facility for extracting uranium yellowcake: Report.” August 5. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/saudi-arabia-nuclear-programme-china-yellowcake-uranium. Accessed: January 31, 2022.

13 | See Gnana, Jennifer. S&P Global, (2022). “Saudi Arabia to develop 'huge' uranium resources in energy diversity push: minister.” January 12. https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/electric-power/011222-saudi-arabia-to-develop-huge-uranium-resources-in-energy-diversity-push-minister. Accessed: January 31, 2022, and CNN (2022). “Saudi Energy Minister: We have a huge amount of uranium, and we will exploit it.” January 13. https://arabic.cnn.com/business/article/2022/01/13/saudi-energy-minister-yellow-cake. Accessed: January 31, 2022.

14 | Fitch Solutions Country Risk & Industry Research (2021). Saudi Arabia Crime, Defence & Security Report, 2021. London: Fitch Solutions Group. P. 26

15 | SIPRI Fact Sheet (2022). “Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2021.” March 15. https://www.sipri.org/publications/2022/sipri-fact-sheets/trends-international-arms-transfers-2021. Accessed: March 20, 2022.

16 | Al- Tamimi, Naser. European Council on Foreign Relations (2019). “The GCC’s China Policy: Hedging Against Uncertainty.” In Lons, Camille (eds.) “China’s Great Game in the Middle East.” October 21. https://ecfr.eu/publication/china_great_game_middle_east/. Accessed: February 10, 2022.

17 | Ibid.

18 | Ibid.

19 | CGTN (2021). “China, Saudi Arabia vow to oppose interference in other countries internal affairs.” March, 25. https://news.cgtn.com/news/2021-03-25/China-Saudi-Arabia-vow-to-oppose-interference-in-internal-affairs-YUuoTSUFbO/index.html. Accessed: February 8, 2022.

20 | Martin, Matthew. Bloomberg (2021). “Saudi Wealth Fund Moves Step Closer to Direct China Stock Deals.” November 4. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-11-04/saudi-wealth-fund-moves-step-closer-to-direct-china-stock-deals. Accessed: February 1, 2022.

21 | About 60 percent, or USD 149 billion, of the Saudi budget in 2021 derived from oil. The kingdom needs to diversify income sources as world demand for fossil fuels shifts. https://www.ft.com/content/6dce7e6b-0cce-49f4-a9f8-f80597d1653a

22 | IISS (2021). “Relations between China and the Arab Gulf states.” Strategic Comments, 27(10), iv-vi. DOI: 10.1080/13567888.2021.2021685

23 | Economist Intelligence Unit (2021). “Middle East is highly exposed to climate change.” November 18. https://www.eiu.com/industry/energy/middle-east-and-africa/saudi-arabia. Accessed: January 31, 2022.

24 | Allison, Graham. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, (2021). “The Great Rivalry: China vs. the U.S. in the 21st Century.” December 7. https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/great-tech-rivalry-china-vs-us. Accessed: January 31, 2022.

25 | IISS (2022). “The Military Balance 2022.” https://www.iiss.org/events/2022/02/military-balance-2022-launch. February 2022. Accessed: February 14, 2022.

26 | Pollock, David. Washington Institute for Near East Policy (2020). “Saudi Poll: China Leads U.S.; Majority Back Curbs on Extremism, Coronavirus.” July 31. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/saudi-poll-china-leads-us-majority-back-curbs-extremism-coronavirus. Accessed: February 9, 2022.

27 | Statista Research. (2021) “Share of respondents in Saudi Arabia who agreed that China offers a political and economic model they would like to emulate as of September 2019.” October 19, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1091386/saudi-arabia-perception-on-china-s-political-and-economic-model/2021. Accessed: February 2, 2022.

28 | Economist Intelligence Unit (2021). “US Afghanistan withdrawal: the impact on MENA geopolitical risk.” September 3. https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/geopolitics-in-the-middle-east/. Accessed:

January 30, 2022.29 | Fitch Solutions (2021). “US Unlikely To Substantially Reduce Gulf Military Presence Over Next Decade.”

March, 2. https://www.fitchsolutions.com/defence-security/us-unlikely-substantially-reduce-gulf-military-presence-over-next-decade-02-03-2021. Accessed: February 9, 2022.30 | Fitch Solutions Country Risk & Industry Research (2021). Saudi Arabia Country Risk Report, Q1 2022.

London: Fitch Solutions Group.31 | Cohen, Zachary. CNN (2021). “CNN Exclusive: US intel and satellite images show Saudi Arabia is now building its own ballistic missiles with help of China.” December 23. https://edition.cnn.com/2021/12/23/politics/saudi-ballistic-missiles-china/index.html. Accessed: February 8, 2022.

32 | Al-Tamimi. “The GCC’s China Policy: Hedging Against Uncertainty.” Ibid.